Stargazing in November: The solar system’s behemoth

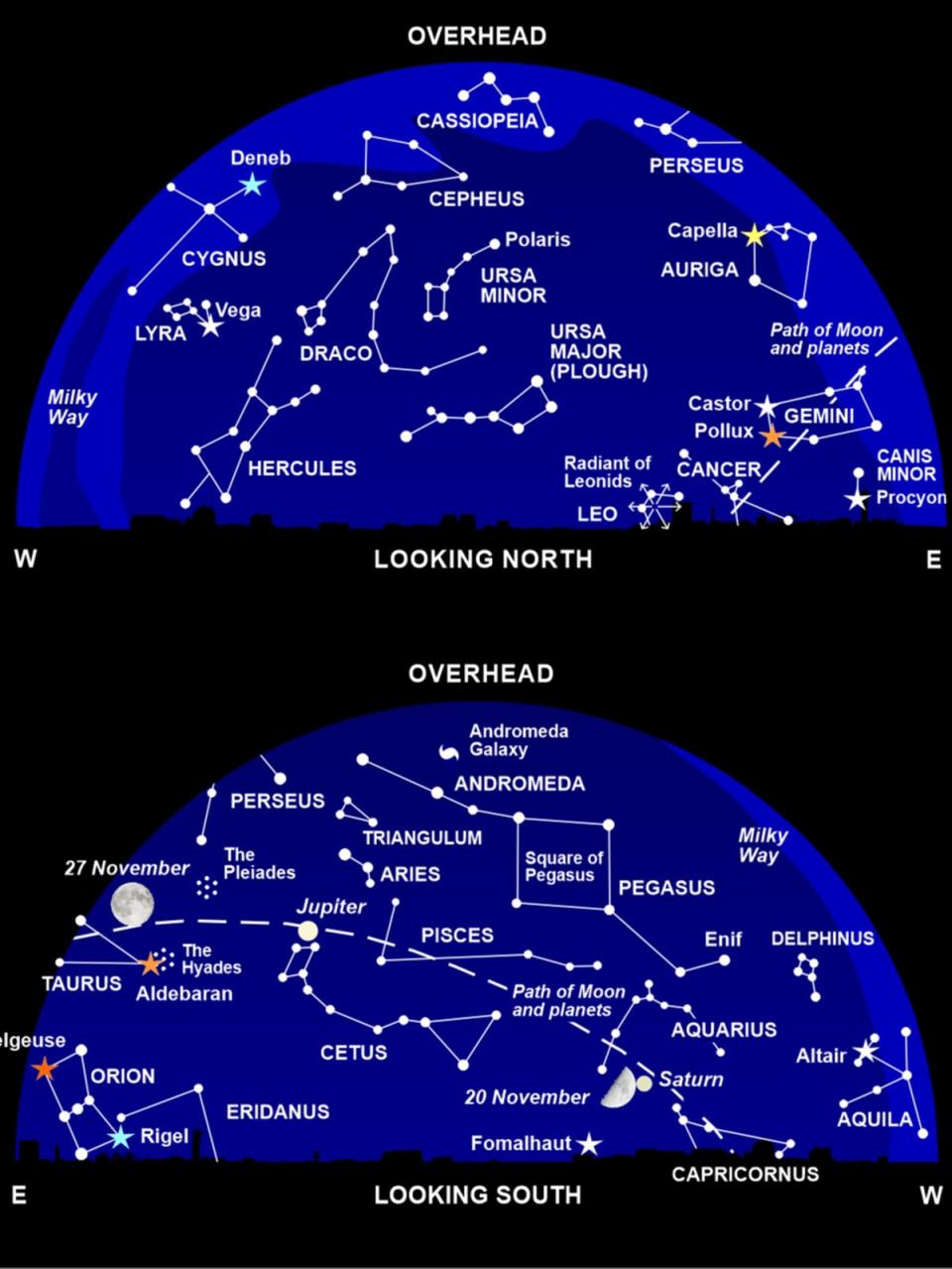

This month Jupiter is magnificent all night long, as the planet is at its closest this year. You can’t miss it, high in the south, outshining all the stars with its steady yellow-white light.

And Jupiter is the planet of superlatives, as befits a world that’s named after the king of the gods in the Roman pantheon. It held the same title to the Greeks, as their head deity, Zeus; and to the Babylonians as supreme god Marduk.

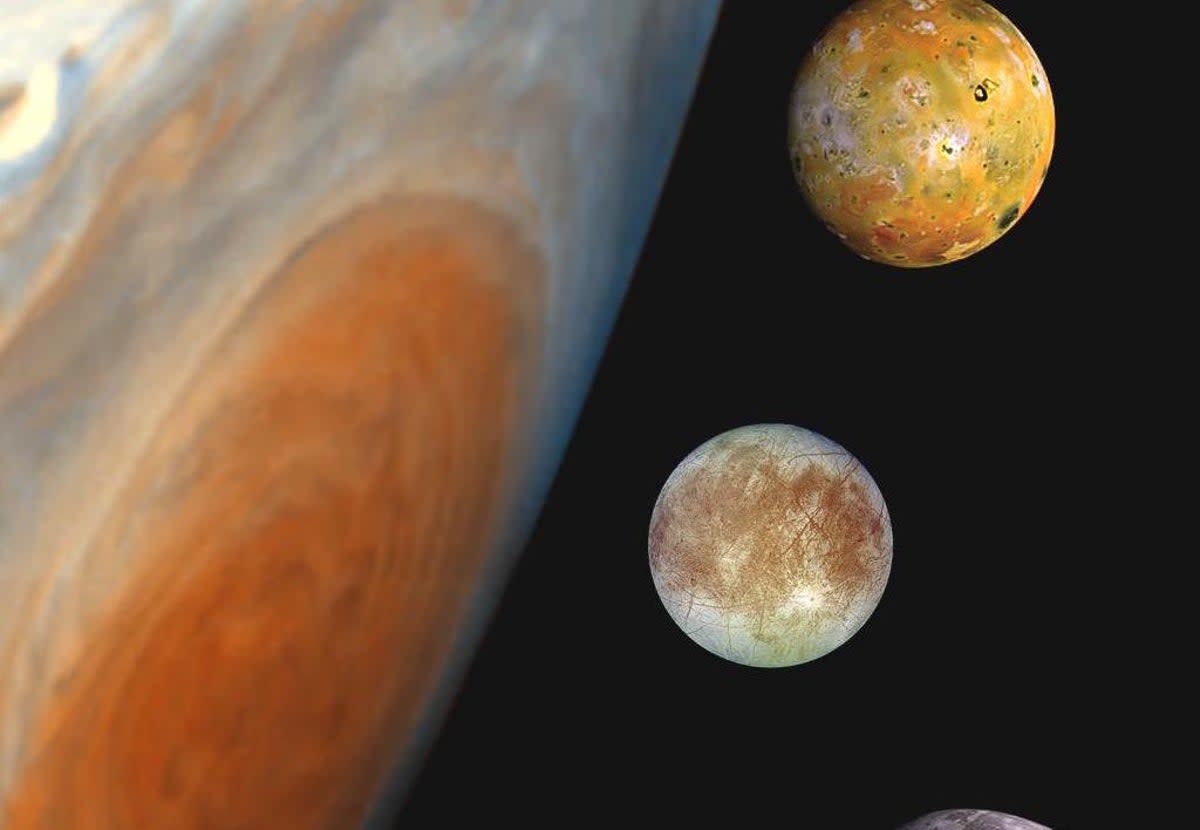

Look closely, and can you see a tiny “star” or two next to the planet? Jupiter has the largest moons of any planet, and people with extremely good sight can make out at least the biggest of the bunch – Ganymede – with the naked eye. My sight has never been that good, but I always enjoy looking through even the smallest pair of binoculars to spot Jupiter’s four major moons strung out to either side of the planet, and constantly changing their position from night to night as they orbit their giant master.

Ganymede is the largest moon in the Solar System, and even surpasses Mercury in size: if Ganymede orbited the Sun in its own right, it would count as a planet. Callisto is not much smaller, while icy Europa and volcanic Io are about the size of our own moon.

These are just the leading lights of the greatest collection of moons of any planet. Jupiter’s powerful gravity keeps at least 95 moons in orbit. That’s the total discovered so far: astronomers estimate that its entire retinue must far exceed 100 moons.

And the planet itself breaks all the records. Jupiter is the biggest world in the solar system, so gigantic that you could fit all the other planets inside it, with room to spare. It could gobble up our planet Earth 1300 times over.

Despite its huge size, Jupiter spins round faster than any other planet, Its ‘day’ is just under 10 hours long, As a result, Jupiter’s equatorial regions are racing around 30 times faster than the Earth’s equator, making the planet bulge out into a tangerine shape that’s visible even through a small telescope.

Running around this whirling globe you can spot light and dark bands – layers of cloud stretched out by the high-speed winds. The white zones are streaks of high-altitude clouds of pure ammonia crystals; between them, we look down to brownish belts where the clouds are tinged by molecules containing sulphur and complex molecules containing carbon.

Like a ball-bearing rotating between these atmospheric streams, the Great Red Spot is an eddy that’s been a feature of Jupiter’s atmosphere for two centuries or more. In Victorian times it was three times the size of the Earth, but now it’s shrunk down to ‘only’ the size of our planet. The top of the Great Red Spot rears high above the other clouds, where it’s exposed to the Sun’s ultraviolet light which rearranges colourless molecules into more complex and garish compounds: in other words, its ruddy hue is a case of sunburn!

Near the equator, Jupiter’s cloud systems are quite orderly. But around the poles, heat rising from inside the giant planet creates enormous storms wracked by the most powerful lightning bolts in the Solar System.

Jupiter is made of gas throughout, with no solid surface, and it’s gradually shrinking under its own gravity. The compression generates heat, and as a result the planet radiates twice as much heat into space as it receives from the Sun. Jupiter’s core has a temperature of 35,000 degrees Celsius, more than six times hotter than the solar surface.

And the planet’s central regions are filled with hydrogen so dense that it behaves like a liquid metal, laced with immense electrical currents that generate the most powerful magnetic field of any planet. Even out where Jupiter’s inner moons circle the planet, the radiation trapped by this magnetism is so intense it would kill any astronaut visiting the giant planet.

Nonetheless, many robotic craft have braved these dangers to transmit data from close proximity. Currently orbiting Jupiter is the Juno mission, which is sending back stunning images of the cloud tops. On its way is JUICE, the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, while Europa Clipper will be launched next year. Expect more records to be broken as these spacecraft probe the still-hidden secrets of the solar system’s behemoth!

What’s Up

Jupiter is the star of the show this month. The giant planet overshadows its fellow gas giant world, Saturn, over in the south-west. While brighter than the stars in its vicinity, Saturn is still 30 times fainter than Jupiter.

Above and between these planets lies a large square of stars marking the body of Pegasus, the flying horse. Oddly enough, old star charts depict this celestial equine upside down as he soars through the heavens, so the stars to the right depict his neck and head with his nose – the star Enif – pointing upwards.

The stars to the upper left of Pegasus trace out the slim shape of princess Andromeda, with a small constellation of three stars below aptly named Triangulum.

Over on the eastern horizon, you can spot the bright stars of winter beginning to rise: first up is Taurus (the bull), with the pretty star cluster of the Pleiades near Jupiter. Lower down, the great hunter Orion is beginning to climb up over the horizon.

Let’s hope for clear weather on the night of 17 November, as the Earth charges into debris shed by Comet Tempel-Tuttle, which burns up as a shower of shooting stars that seem to stream out from the constellation Leo (the lion). Most years the Leonid meteor shower is a bit of a fizzler, but in 2023 we may encounter a denser stream of interplanetary rubble, so look out for bright fireballs lighting up the sky, especially before dawn on 18 November.

And all month, early birds are treated to the glorious sight of Venus, as the brilliant Morning Star. On the morning of 9 November, Venus lies right next to the Moon in a splendid celestial tableau to start off the day.

Dairy

9 November, early hours: Moon very near Venus

13 November 9.27am: New Moon

17 November: Maximum of Leonid meteor shower

20 November, 10.50am: First Quarter Moon near Saturn

25 November: Moon near Jupiter

26 November: Moon near the Pleiades

27 November, 9.16am: Full Moon

30 November: Moon near Castor and Pollux

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2024’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky next year