Stargazing in October: Halloween fireballs

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When you’re out trick-or-treating this Halloween, keep an eye on the sky for an unusual cosmic treat – brilliant shooting stars called fireballs. They may represent the afterlife of a huge comet that died 20,000 years ago.

Every year, we experience regular showers of shooting stars, when the Earth ploughs into trails of dust shed by comets as they tramp around the solar system. This month, for instance, we’ll enjoy a display of Orionid meteors on the night of 21 October: these are fragments littering the orbit of Halley’s comet, that burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere way over our heads and seem to stream outwards from the constellation Orion.

From late October into mid-November, we cross the path of a comet called Encke – named after German astronomer Johann Encke who calculated its orbit in 1819. While a comet like Halley sweeps in from the far parts of the solar system, Encke’s comet doesn’t stray further out than the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, looping around the sun in just 3.3 years. It’s a small and faint beast, though, so only rarely is Encke’s comet visible without a telescope.

The Earth sweeps up a few fragments from Encke every year in October-November, as a drizzle of meteors called the Taurids. They are so desultory that I usually don’t mention them in this column. But this year is different.

Alongside the tenuous band of dust spread along Encke’s orbit, astronomers believe there are parallel streams thick with bigger chunks of rock, up to the size of pebbles. In 2022, the Earth is set to run into one of these streams, and the larger chunks of debris will blaze into incandescence as they rain down.

It’s occasionally happened before. In 1997, a fireball associated with Encke’s comet shone as brilliantly as the full moon. And in 2005, astronomers saw a flash on the moon when a pebble-sized fragment impacted the lunar surface.

And pebbles aren’t the largest members of these streams. Recently, astronomers Ignacio Ferrin from Colombia and Vincenzo Orofino from Italy have closely examined the orbits of many asteroids and comets traipsing through the inner solar system. They conclude that 88 of them follow similar paths to Encke’s comet, in bands of debris that are a serious hazard to our planet.

According to Ferrin and Orofino, two of the most damaging impacts in recent history occurred as the Earth crossed this cosmic minefield. In 2013, a space rock 20 metres across crashed to Earth near the Russian city of Chelyabinsk, injuring 1,500 people. And an even larger piece of space debris wreaked worse destruction in 1908, in the – fortunately – sparsely populated Tunguska region of Siberia.

So where did these cosmic projectiles, both great and small, come from?

Back in 1982, British astronomers Bill Napier and Victor Clube published a far-sighted and daring theory. Around 20,000 years ago, they claimed, a huge comet headed into the inner solar system. Assaulted by intense heat and gravitational forces as it swung close to the Sun, this 100-km-diameter dirty snowball disintegrated into a myriad fragments, including Encke’s comet and the Tunguska projectile.

Conventional astronomers shook their heads: why invoke such an extreme scenario, just to explain a small comet and a random impact on the Earth?

But now things look different. The Chelyabinsk impact came along. Ferrin and Orofino have shown Encke’s comet is just one in a formation of almost a hundred asteroids and comets. Finally, the idea of a super comet doesn’t seem so whacky now: the Hubble Space Telescope has measured the diameter of the distant comet Bernardinelli-Bernstein as over 120 km.

The more we learn, the more we should fear the mortal remains of Napier and Clube’s super comet. As we are treated to a display of Halloween fireballs, let’s just hope we’re not subjected to the trick of a huge space rock on collision course…

What’s up

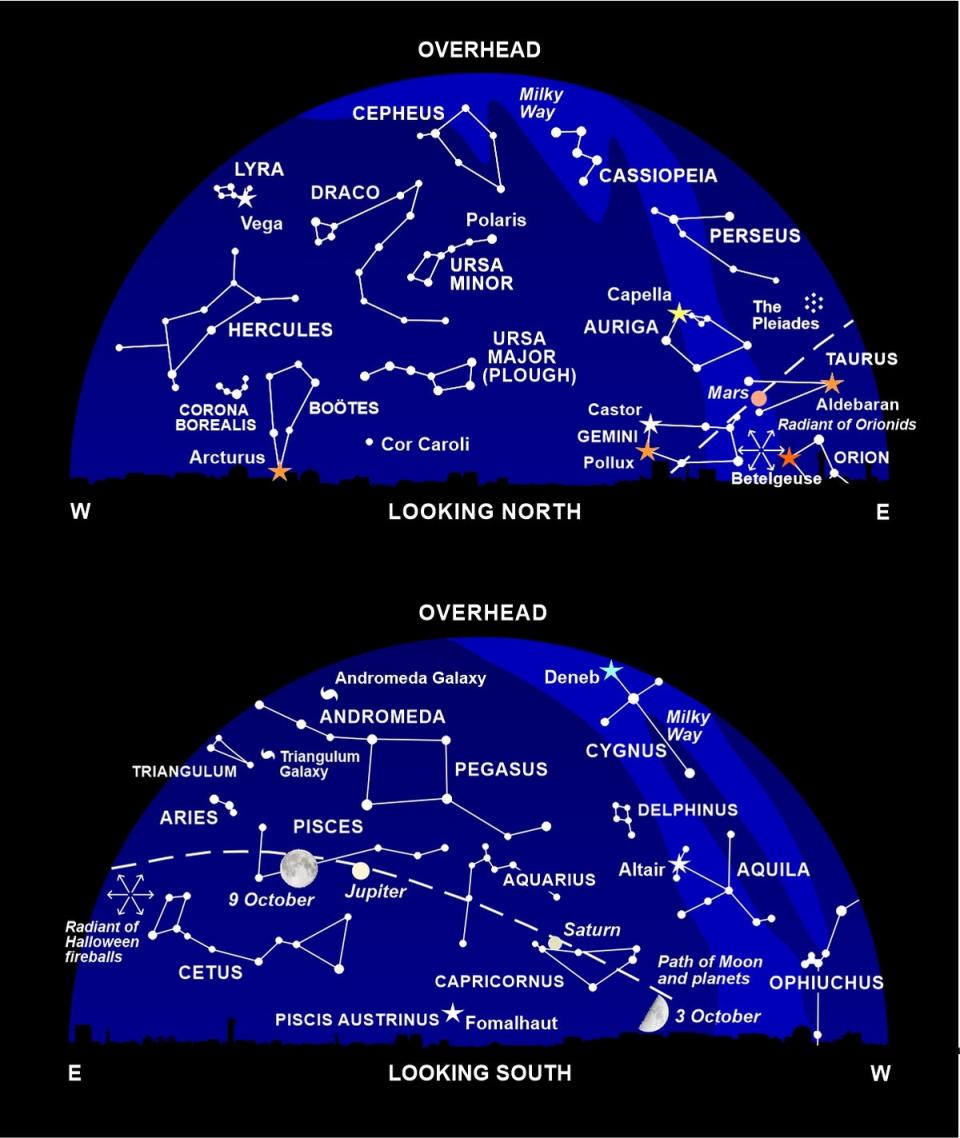

Giant planet Jupiter is still the most brilliant object in the night sky, after the moon, and visible all night long towards the south. But it now has a challenger. To Jupiter’s left you’ll find Mars rising at about 8.30pm, and brightening throughout October until it matches the brilliance of the most prominent stars.

Well to Jupiter’s right is the solar system’s second-largest world, Saturn, with its famed ring system a glorious sight through a small telescope.

The distinct pattern of four stars marking out the Square of Pegasus lies above Jupiter, with the W-shape of Cassiopeia higher up still. Towards the east, we can now see the stars of winter beginning to rise. Aldebaran, marking the eye of Taurus (the bull) lies to the right of Mars, near the pretty little star cluster of the Pleiades (the seven sisters). And over in the northeast, bright Capella – in the constellation Auriga (the charioteer) – is now well in view.

It’s a great year for observing the annual Orionid display of shooting stars, on the night of 21 October, as the moon is well out of the way and the sky will be dark. And on the last night of the month, watch out for the Halloween fireballs (see main story).

Early birds can catch Mercury putting on its best morning appearance of the year, low on the eastern horizon mid-month, and rising at about 6am.

Last, but far from least, there’s a partial eclipse of the sun on 25 October. As seen from London, the moon starts moving in front of the sun’s disc at 10.08am; the eclipse is greatest at 10.59am; and the show is over at 11.51am. (These times may vary by a few minutes depending on your location in the UK.)

Diary

8 October: Mercury at greatest elongation west

9 October, 9.55pm: full moon

12 October: moon near the Pleiades

13 October: moon near Aldebaran

14 October: moon near Mars

16 October: moon near Castor and Pollux

17 October, 6.15pm: last quarter moon near Castor and Pollux

21 October: maximum of Orionid meteor shower

25 October, 11.49am: new moon, partial solar eclipse

28 October: moon near Antares

30 October: British Summer Time ends

31 October: Halloween fireballs (start of the Taurid meteor shower)

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Philip’s 2023 Stargazing’ (Philip’s £6.99), is a month-by-month guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky next year