We Started a Free Food Fridge in Front of Our House. Here’s How the Whole Thing Fell Apart.

“I saw a woman take all the meat out of the fridge,” a woman named Rita wrote in a post.

The pantry Facebook group was going nuts.

During the pandemic, I stumbled into running a food pantry and fridge from our front yard in Las Vegas. I say stumbled because I’d put some toilet paper and odds and ends into our Little Free Library and then people kept coming, looking for more. It rapidly evolved. First, a dry goods area, soon joined by a fridge with fresh vegetables, meats, and dairy. Before long, I was stocking it multiple times a day, from supermarkets letting go of still-good vegetables, herbs, and fruit to food bank giveaways and cobbled-together Costco runs funded by neighbors and friends.

Things with the pantry ran pretty smoothly through the first year. Then, things began to break down. More accurately, perhaps, things were breaking down for the people we served. The scarcity around the pandemic took its toll on how people thought and acted.

And the pantry was a kind of physical monument to that decline.

The decline started right around the time the Facebook group was going nuts, eight months or so in.

“She took everything and I was standing right there waiting,” Rita wrote.

Jose, a young guy who contributed far more than he took, had dropped off 40 pounds of sectioned chicken from a neighboring hunger charity.

That charity’s director was none too happy with Jose, even though that chicken had itself come from another food bank. This was my first hint that hunger work could be competitive, divisive, and not entirely about the people we served.

“Please do not give food from our food pantry to this pantry,” she scolded Jose.

In my head, that charity director was “the Pepsi Lady.” Part of her program was “Soda Day.” A semitrailer, overloaded with 2-liter soda bottles, would pull up as people formed long, trailing lines for their free soda and sport drinks.

The Pepsi Lady was a member of our Facebook group.

I ignored her and focused on the group members freaking out in the comments, all of it because someone had to witness another person taking food that could’ve been theirs.

Jesus, how did we get here? I kept thinking.

It was the perfect example of how services can go wildly off the rails. Even our tiny pantry, a small and simple organization designed specifically to help people struggling during a temporary emergency, can start chasing its own tail.

“That’s freaking ridiculous,” wrote Lateema. “I had someone try to see what I had in the bag I was dropping off, before I could even put it in the fridge.”

Rita talked about waiting to see what would be left after the people in front finished.

“They grabbed it all,” she wrote. “I waited patiently to see what they would leave me.”

Watching a woman take every bit of food was a serious trauma trigger. An up-close reminder of how scarce things had become. And how precarious.

The Facebook messages continued. About the competition for food. How it felt to be on the losing end of the resources grab. All of it a mirror of their larger pandemic experience. It was a bloodletting.

A purge of the world’s chronic thoughtlessness about their well-being.

Then, a plan started to emerge. We worked it out together so there could be calm. The pantry would still source and offer veg and groceries 24/7. I would still refill it—five or six times a day. But the meat would live in the extra freezer on my back porch. People could make appointments to get meat for their families when it was convenient for them, and they could have whatever types and amounts they wanted. Their choice.

We posted these new rules, in English and Spanish, to make it official.

This brought a temporary calm.

Freedom is critical, but rules are safety. There needed to be balance.

But I couldn’t help but feel as if something unsettling was happening at the pantry.

The pantry taught me, in slo-mo, in real time, how poverty and scarcity impact people’s brains.

Economist Anandi Mani of the University of Warwick, along with researchers from Harvard, Princeton, and the University of British Columbia, has studied what happens when a person’s brain is stressed by poverty and scarcity. They looked at the frontal cortex, where executive function manages memory, focus, planning, multitasking, and, a biggie, emotional regulation.

The stress of poverty, they noted, put brains into cognitive overload. The stable brain, the delightfully regulated brain, was smashed to bits. Planning got hard, sluggish. People made short-term decisions when long-term ones would be so much better. Think: payday loans, losing track of bills, neglecting critical issues—or freaking out while watching someone take all the food they were hoping to get.

Brains in comfortable, well-stocked homes didn’t have this stress.

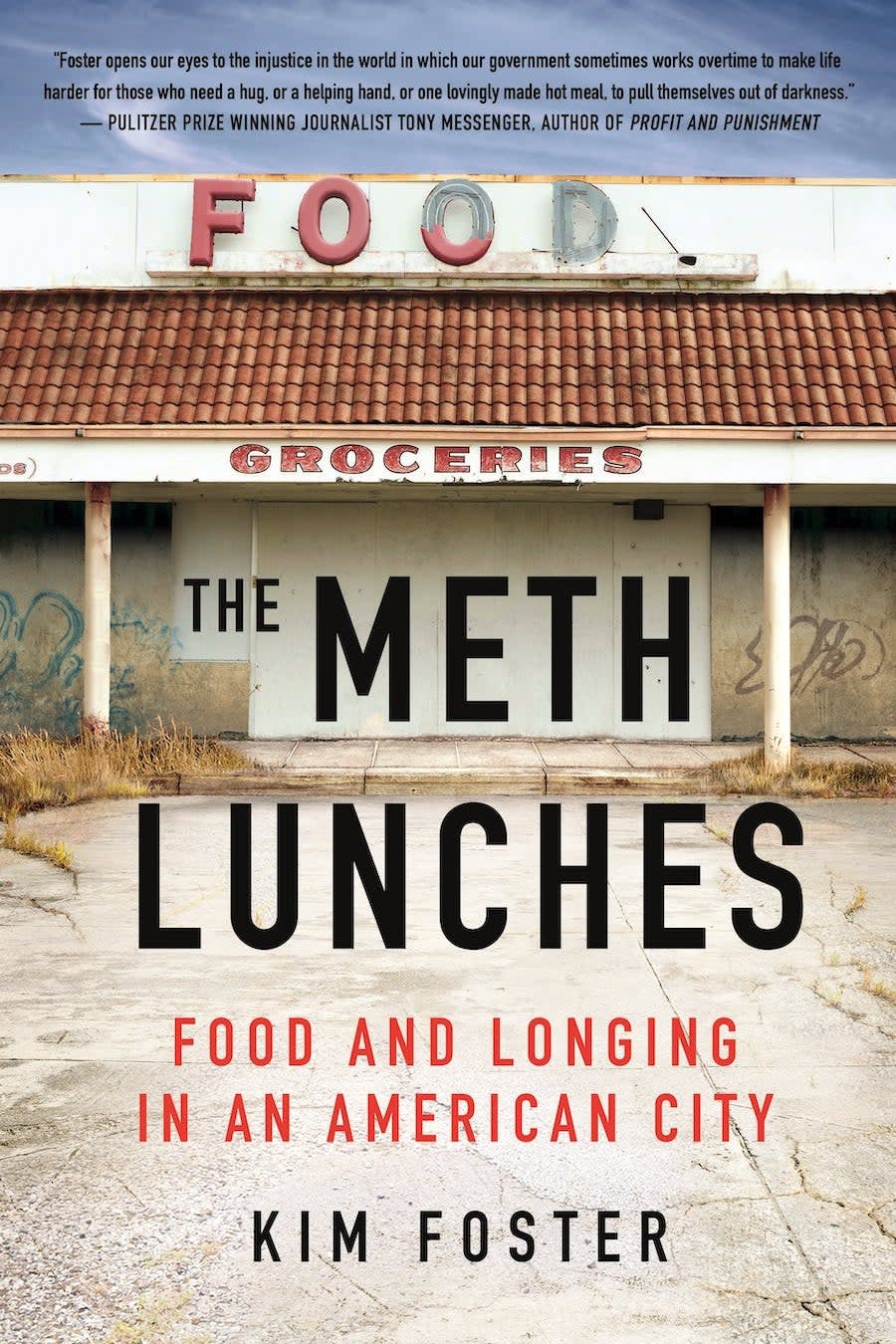

As the pandemic continued, this stress effect was becoming, quite obviously, more debilitating. I could see it play out. It’s part of the reason I wrote my book The Meth Lunches: Food and Longing in an American City, about how people eat, shop, and cook when their brains are crushed by the forces of struggle, like poverty, incarceration, hunger, family separation, and eviction.

I saw the toll in my own front yard.

Local news loved the idea of a front-yard pantry. But the coverage made things hard to manage. We were deluged with need. And also donations.

People cleaned out their home pantries and dropped off grossly expired food. Stuff that had festered in their cupboards for a decade.

Saltines. Expired in 2008.

Breadcrumbs. 2010.

Instant ramen. 2014.

A half-used jar of off-brand mayonnaise. Expired, molded-over cottage cheese. Specialty products like bee pollen, cornichons, olives, and things with truffles suspended in them that had obviously come from a 2012-era corporate gift basket.

People often drove up. Stopped. Opened their car door and dropped bags of groceries in the dirt. Then shot off as if the police were in pursuit. Many times, these foods were sunbaked and dust-caked before I could sort through them. I marked my time with how many trips I made to a dumpster at a nearby school.

I checked and double-checked what came in, but some of it was slipping by me.

Aisha, a member of the pantry Facebook page, told me her daughter was sick. She was vomiting after eating pantry ramen. Aisha checked. Instant ramen from the ’90s.

The little girl was fine. But I wasn’t.

Food safety was always a huge concern, something we worked hard to manage, and here I was, poisoning children.

Then, unhoused people discovered the pantry. Our initial customers were out-of-work people, young families, and those picking up for elderly and disabled people. Many lived in precarious forms of housing, like weekly hotels, but most had cars and roofs. Many were in school or parenting babies. They had kitchens to cook in, so a lot of the food was designed to facilitate cooking.

I wanted to help unhoused people, and we did daily, but they had substantially different needs, even down to the kinds of foods they preferred and needed to manage their more itinerant lives. I noticed almost immediately their collective impact on the pantry.

And it was substantial.

Many of the most desperate people in our communities, those who are unhoused, can experience untreated mental illness, traumatic brain injuries, and, many times, unchecked substance-use disorders. And they brought all of this to the pantry.

They ate right from the fridge. Dropped wrappers and chunks of food. Tossed plastic and paper wrappers in plants and trees. In the dead of night, someone drank milk from a half-gallon jug. They capped it and put it back. There were scraps of food everywhere.

Meanwhile, because people always want to be the helpers and not the helped, neighbors often tried to offload their surplus possessions onto the pantry. A lady came to me with a carload of men’s clothes, washed, pressed, and hung neatly on hangers in her back seat.

“Thank you, but no,” I said.

“Are you sure?” she asked. “ ’Cause you know, they were my husband’s before he died, and they are in great shape.”

Someone dropped off old golf clubs.

My policy was If you leave it, it goes in the trash. Why? Because if I didn’t, it would become a free-ass yard sale. A clusterfuck of things no one wanted that would grow to be the size of a Northeastern snowbank. A tall, useless pile of chaos.

Their desire to be helpful. Right there on our doorstep.

I learned. People needed guardrails.

I was standing just outside my front door. It was morning. Everything was quiet.

It had been a long night at the pantry. As usual, it had been cleaned out. That was to be expected.

The fridge door was left wide open and the shelves were removed. Nowhere to be found. Whatever food was left was lying haphazardly on the curb and in the street, along with squashed cans that had once had beer in them.

And a lot of cigarette butts.

The shelves were really gone. I looked everywhere. They took my shelves.

I thought of my first therapist, Gwen, who had told me, years before, that when people trashed a public restroom, when they left behind their bloody tampons, their dirty pads, wadded-up tissue stuck to the floor, mounds of shit in the bowl with no attempt to flush it away, that these people were expelling and expressing their anger.

They dumped their anger at the world, anonymously.

It was a big Fuck you; do you hear me?

See me.

See my anger.

See how badly I feel.

Deal with that.

You think I’m not here. I am.

I am.

The people with the most chaotic lives were right here. I felt the weight and anxiety and brokenness and chaos of their attempts to survive. I felt it and knew that it is much harder to live it than to sit here and empathize. Much harder to live it than pick up a messy yard. Much harder to live it than for me to give people grace for just living as best they can.

The pantry was a public toilet.

There were now people who buzzed our front door at all hours of the day and night, asking for food. Whatever boundaries we created had been mostly obliterated. People were so desperate; the niceties were done.

There’s one woman, Shaina. She came at least once a week. But never during the day. Always with “three families” waiting in the car. They were always in a rush. Always with the car idling outside.

“Hi. I know it’s late,” she would say, putting her body in the door like a lever so it had to stay open.

One night, I was dozing on the couch after taking an edible to put myself to sleep. I was fuzzy.

“You have soup!” she exclaimed, eyeing the makeshift shelves in the foyer filled with canned food. Bags of baking supplies. Jars and boxes.

“Can I get some soup?”

“Um, sure.” She didn’t wait for me. She was halfway into my foyer and dropping cans into her box.

I wanted to lie down and melt back to sleep. But Shaina was in my house.

I wanted to say no. But I knew she would roll over me anyway. I was too tired to fight. She was too tired to give up.

The next thing I knew, I was padding to the side freezer in bare feet.

I took out packs of meat to load into the box she was making. I grabbed eggs, cheese, bread, and cold cuts.

“Um, OK, what else do you need?”

“Everything.”

I walked out to the front yard in bare feet and a wool sweater wrapped around me.

What the fuck had gone on during the night?

People must’ve been feeling out of control. It was trashed. The milk crates were gone again. The fridge shelves—I used racks from my oven to replace the shelves that had been taken—had been removed again and thrown into our hedge.

Someone had opened every bottle of liquid and poured it everywhere.

The fridge was sticky and gross.

The smell of urine smacked me in the face.

My yard was postapocalyptic.

A neighbor saw me outside and came to me, breathless. He had sat outside on his front porch the night before, beer in hand, enjoying the sky spin colors over the Stratosphere, the tallest observation tower in the U.S. and also a beacon in the sky that calls us home to our neighborhood. He watched a stream of people make their way down the street.

Then more.

Then more.

He went to bed, and someone trashed their mailbox. Looking for uncashed checks.

“I’m worried that the fridge is changing the neighborhood,” he said.

“You know, I didn’t want to move east of Las Vegas Boulevard,” he told me. They had recently bought a house across the street after moving here from El Salvador.

“But things weren’t that bad on this street.”

This family had always supported the pantry. I listened to them when they said it was time.

Later in the afternoon, as if the universe were summoning all of its communication abilities, someone posted an official City of Las Vegas notice of closure on the pantry. It demanded the pantry’s removal, detailing potential fines.

Someone had called the city.

I posted on the Facebook page that the pantry was closing.

“Everything must go,” I said to people as they cleaned out our house, freezers, and pantry.

Neighbors came and washed down the fridge. My kids loaded the library with books again. My husband dragged the fridge into the backyard.

By the end of the week, there was no more pantry and no sign it had ever existed.

This is as it should be.

Pantries should never run forever. They should be efficient and stealthy during their temporary appointments during a crisis, but they make poor long-term resources for the community. Everyone should be able to shop for and pick out the food they cook and eat. That people live their whole lives on the food handed to them at pantries and banks is unacceptable.

People still came, but now for books. And to add more in.

It would take weeks for word to filter its way back around to me. But several sources told me that the call to the city to close down our pantry had come from the Pepsi Lady.

I didn’t know whether to be mad at her. Or hug her.