The state capital of reading problems, Milwaukee Public Schools looks at how to turn things around

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is the first of two stories focusing on teaching Milwaukee students to read. This is part of the By the Book series, which examines reading curriculum, instructional methods and solutions in K-12 education to answer the questions: Why do so many Wisconsin kids struggle to read? And what can be done about it?

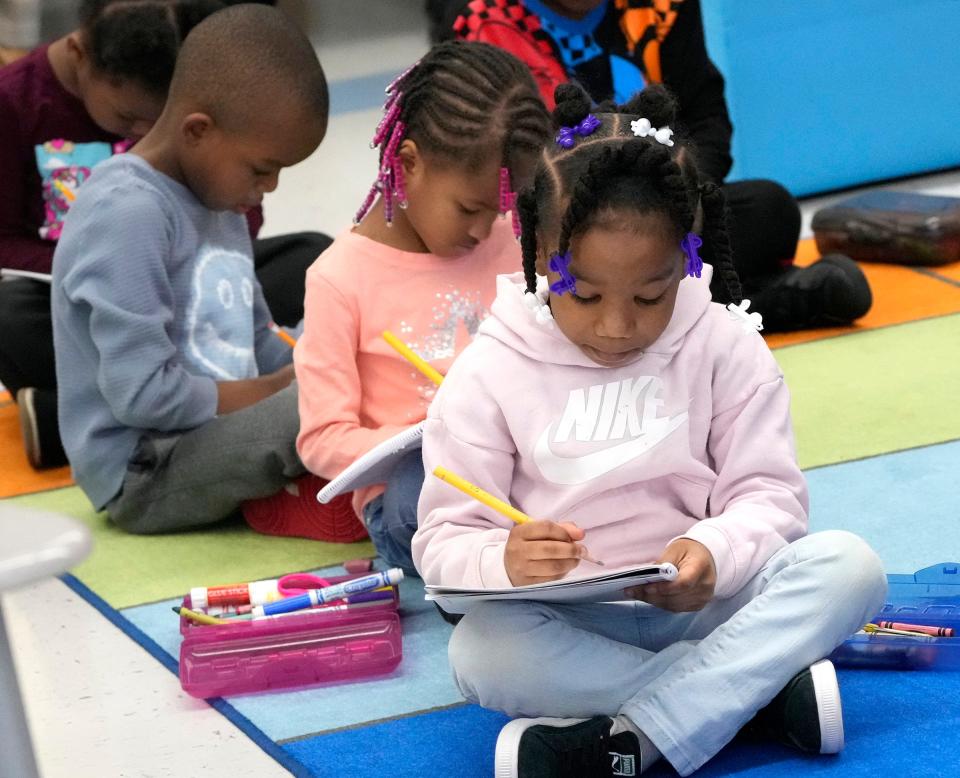

Katie Beattie is leading 14 students in a 5-year-old kindergarten class in developing their language arts skills. The students are paying attention; the atmosphere is cheerful.

“We’re going to write about our favorite color,” says Beattie, a 20-year-veteran teacher. “Our first word is ‘my.’” She asks, “What does ‘my’ start with?” She writes the word on a smart board screen that all can see, while the students write the word in paper journals. Together, they write, “My favorite color is,” sounding out the letters and spelling the words. The students name their favorite colors, including one who says, “Rainbow.”

It is a positive classroom scene at Milwaukee Public Schools’ Hawthorne Elementary, 6945 N. 41st St. It reflects changes in MPS aimed at lifting the reading levels of more students. The changes include use of curriculum materials that are in line with the phonics-oriented “science of reading,” more training for teachers and more effort to connect with families.

More: By the Book: We're investigating why many Wisconsin kids struggle to read. We want to hear from you.

But is it enough? Is it deep enough, wide enough, intense enough, compared to what some schools are doing and what would be needed to have substantial effect?

A variety of challenges could contribute to MPS' low reading scores

Milwaukee is the state capital of reading problems. In fact, it is one of the nation’s capitals of reading problems. Few large school systems have lower reading success overall than MPS.

Year after year, MPS reading scores are abysmal, strong signs of the problems with educational success that lie ahead for many students. There are bright spots; some MPS schools consistently have better results.

But overall, in spring 2022 — the most recent results available — more than half (54.1%) of MPS third- through eighth-graders were rated “below basic” in reading on Wisconsin’s Forward tests, while 26.2% were at the basic level and 14.1% were rated proficient or advanced. Another 5.6% didn’t take the tests. Among Black students, 7% were advanced or proficient and 64.7% were below basic. In some schools, fewer than 2% of students were proficient and none were advanced.

It is fair and important to note that the overall success of students in private, parochial and charter schools generally wasn’t much different, although some schools stand out for above-average success year after year.

Specifically, in spring 2022 results for Milwaukee students using publicly funded vouchers to attend private schools, 41% were rated as below basic, 32% as basic, and 19% as proficient or advanced. The voucher percentages include ninth-, 10th- and 11th-grade students.

It isn’t that educators in MPS — or non-MPS schools — aren’t trying. But they face big challenges. And many are committed to the profession, some of them for entire careers.

But big questions hang over them and their students, questions that illustrate the controversies nationwide over how to teach reading, vocabulary, writing, comprehension and other language skills.

Could the teachers be doing things that would bring more success? How much do different teaching techniques or curriculum materials matter? What can a classroom teacher or an entire school accomplish, given what goes on in children’s lives outside of school?

Nationwide, children from low-income families have less success as readers than children from high-income families. Statistics show that Black and Hispanic children have less success than white children. Children with unstable daily lives, including problems with housing, food and health care or abusive or neglectful parenting, have less success than those with more stable lives.

Curriculum isn't the only thing affecting reading success

Kathy Champeau, a leader of the Wisconsin State Reading Association, is a long-time supporter of the “balanced literacy” approach to teaching reading. It calls on a range of ways to teach reading, including ones that phonics advocates argue are ineffective, and it emphasizes the role and professional judgment of teachers, rather than a structured curriculum for teachers to follow.

More: A bipartisan consensus could be growing on how to teach reading statewide

In a recent interview, Champeau said that even in a school district where schools use the same curriculum, higher-income students do better than lower-income students, a sign of the effect of forces outside school walls.

Her observation is true for Milwaukee, where some public schools with more middle-class student bodies have better reading results than those serving lower-income students. The schools with better results also tend to have more stability in their teaching staffs and fewer teaching vacancies.

Champeau said it is “simplistic” to think a curriculum change alone would solve reading problems. She emphasized the need to support teachers in their work and to deal with children’s issues outside of school.

Even leading advocates for the science of reading, with its strong emphasis on structured lessons and phonics, agree that adopting the approach is not the complete answer to reading problems.

Reading is more than decoding words

Emily Hanford was the lead reporter in podcasts for APM (formerly American Public Media) that have been heard by millions and have catalyzed action to increase use of science of reading curriculums. Her podcast series, “Sold a Story," issued in fall 2022, played a big role in putting on the defensive major balanced literacy figures such as Lucy Calkins of Columbia University, main author of the widely used “Units of Study,” and Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell, creators of a popular “leveled literacy” system of rating books.

In an interview while Hanford was in Madison for a conference, I asked how much effect there would be if there were a big increase in science of reading programs. “Some,” she answered. And there is potential for those effects to grow if the efforts are carried out well.

But teaching reading, she said, is a complex problem and involves much more than teaching phonics and how to “decode” words. “Many things are going to have to change” to have broad success, Hanford said. She pointed to large class sizes in many schools as one of those things.

Mark Seidenberg, a University of Wisconsin-Madison psychology professor, has done extensive research on how eyes and brains work to turn words on a page into understandable content. Nationwide, he is recognized as a leader in research involved in the science of reading.

But, in an interview, he said building children’s skills to figure out words is not the only thing needed. Environmental factors such as homelessness and exposure to lead also affect success in school.

While changing children's overall circumstances is not easy, classroom instruction is “one thing we can do well,” Seidenberg said. Broadly speaking, that is not happening now, he said.

He said reading instruction in school now is often so ineffective that it exacerbates the impact of socio-economic differences, because people with good access to resources can get the help their children need to become good readers, while those without such access cannot.

Hawthorne is example of both problems and potential

Hawthorne Elementary shows some of both the problems and the potential for improvement in MPS.

On state tests in spring 2022, only 2.7% of Hawthorne students scored at the proficient level, and none were rated as advanced. But the percentage who scored at the basic level increased from 13.1% in spring 2021 to 36.5% just a year later. The percent below basic decreased from 85.2% to 60.8%.

Yes, basic is below proficient, but the bar for being rated proficient is set fairly high. Basic can be thought of as putting kids on the playing field and below basic as not really being on the playing field at all. Getting more kids to the basic level is a step forward.

Shantee Williams, who is in her fifth year as Hawthorne’s principal, pointed to changes that have helped, such as increased time daily for reading instruction, improved intervention work with students who are not reading well, more efforts to build relationships with parents and more attention to data on student performance.

She and teachers who were interviewed said they are invested in seeking improvement.

MPS Superintendent Keith Posley said the district is in the second year of using the language arts curriculum HMH Into Reading in 5-year-old kindergarten through fifth-grade classes. It is considered by reading experts such as the nonprofit organization Ed Reports to offer a structured approach in line with the science of reading.

New York City public schools, the largest system in the nation, announced in May that it would require science of reading curriculums in its schools. Each of the hundreds of schools in the system will be required to choose from three approved curriculums. One was HMH Into Reading.

Posley said the new materials require the kind of structure and repetition that kids generally need.

But more is needed to get better results for Milwaukee students than new teaching materials. Giving teachers good training and providing on-the-job coaching are important, Posley said, as is working with parents on what they can do at home and using the help of community organizations such as the Boys & Girls Clubs that offer supplementary reading programs.

He used an important word in looking for the success of reading programs: “Fidelity.” To put it simply, that means carrying out the curriculum consistently and well.

Alan J. Borsuk is a senior fellow at Marquette Law School. Reach him at alan.borsuk@marquette.edu.

Next: This time for sure? A look at efforts past, present and future to improve reading outcomes for Milwaukee students.

Our subscribers make this reporting possible. Please consider supporting local journalism by subscribing to the Journal Sentinel at jsonline.com/deal.

DOWNLOAD THE APP: Get the latest news, sports and more

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: MPS looks at how to improve reading among students