State tests show most Fort Worth kids are behind in reading. Their parents have no idea.

Last year, LaShanta Mire felt good about how her daughter Malaysia was doing in school. Malaysia was a second-grader at Clifford Davis Elementary School in Fort Worth, and she consistently brought home As in reading and language arts.

But Mire knew third grade is an important year for reading, so over the summer, she had her daughter take a reading evaluation at a literacy event. When the results came back, Mire learned Malaysia was reading at a kindergarten level.

At first, Mire was shocked. But looking back, she can see where Malaysia struggled. She knew what sounds each letter combination made, so she didn’t have much trouble sounding out words. But she seemed to have trouble with reading comprehension, Mire said — even when she could piece together what words sounded like, she often didn’t understand what they meant.

“How she had an A in reading, I don’t know,” Mire said.

Mire isn’t alone. Recent polling data suggests the overwhelming majority of parents in Fort Worth think their kids are reading on grade level. And with good reason: In several school districts that serve parts of the city, two-thirds to three-quarters of third-graders brought home As and Bs in reading and language arts, according to figures obtained by the Star-Telegram through open records requests.

But state test results paint a different picture. Across the 12 school districts and 14 charter school networks that operate in the city, most students scored below grade level in reading last spring, according to a new analysis of state achievement data.

Fort Worth reading grades don’t line up with grade-level skills

Across every school in the city, 44% of students met grade-level standards in reading on last spring’s State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness, or STAAR, according to an analysis of test data by the nonprofit Fort Worth Education Partnership. That represents a two-point decline from how Fort Worth students performed on the 2022 STAAR, the analysis shows.

But polling data shows large majorities of parents think their kids are doing well in reading. In a survey in May by Concord Public Opinion Partners on behalf of the Fort Worth Education Partnership and the Sid W. Richardson Foundation, 80% of parents who live in the Fort Worth ISD boundaries said they believed their kids could read on grade level. Nearly all said they thought teaching students to read well is a “very important” function of a school system. Just 1% said they thought it was “somewhat important.”

Notably, 47% of parents told pollsters they were “not confident at all” that STAAR scores are accurate. Over the past few years, research has called into question how well aligned with grade-level standards questions on the state test are. A 2019 study from the Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk at the University of Texas at Austin found inconsistencies in the readability of some test questions. In a separate 2019 study, two professors at Texas A&M University-Commerce found that many test questions had readability levels that were one or two years more advanced than the grade levels being assessed.

Fort Worth mom switches schools after reading assessment

After Mire got the results of Malaysia’s reading assessment, she talked with leaders of the parent advocacy group Parent Shield Fort Worth, which organized the reading clinics, about what to do. They showed her Clifford Davis’ reading scores over the past few years. The elementary school has lagged behind the rest of the district in reading for years. Last spring, just 16% of the school’s third-graders were reading on grade level, down from 20% the previous year. Clifford Davis is home to a large number of refugee students, many of whom hadn’t been in school before arriving in the United States because of circumstances in their home countries.

After seeing how far behind Malaysia was, Mire didn’t feel like she could send her daughter back to Clifford Davis for third grade. So she looked at a few other options before picking Rocketship Dennis Dunkins Elementary School, a charter school in Stop Six. Her daughter started school there last month, and so far, she loves it, Mire said. Every morning, teachers at the school take kids into the auditorium and lead them in dances to get them excited about the day, she said.

But Mire said she knew that moving Malaysia to a new school wouldn’t solve the problem completely. This year, she’s being more proactive about communicating with her daughter’s teacher and making sure her daughter is doing everything she needs to do.

“Whatever it takes for her to get on grade level, I’ll do it,” she said.

Grades, test scores play different roles, FWISD official says

In Fort Worth ISD, which serves the largest share of students in the city, about 67% of third-graders got As or Bs last year in reading and language arts, according to figures released by the district. But only 32% met grade-level standards on the state test, a six-point decline compared to last year, according to results released last month by the Texas Education Agency. Sixty percent of third-graders either met or approached grade-level standards, also a six-point drop from last year, test results show. Education researchers say third grade is a crucial time for literacy, because students who can’t read proficiently by then generally struggle for the rest of their educational careers.

Melissa Kelly, Fort Worth ISD’s associate superintendent of learning and leading, said the grades students get throughout the year serve a different purpose than state test scores. Grades are a way for teachers to give parents updates about how their kids are doing at several points throughout the school year, she said. They’re based on a variety of factors, such as tests, daily grades and projects, she said.

STAAR scores, meanwhile, are based on how students perform on a single test given on a single day at the end of each school year. If a student oversleeps, feels sick or has a bad day at home, they still have to take the test, she said. The test also doesn’t always give equal weight to every concept every year, she said — sometimes it focuses more heavily on some areas than others. So although it’s a major part of how schools and districts are evaluated, the test isn’t always the most reliable indicator of how any individual student is doing, she said.

If parents are concerned about how their kids are doing in any subject, Kelly said, their first course of action should be talking to their child’s teacher. If a student brings home good grades in reading but doesn’t do well on the state test, there are other things teachers can look at to see what’s going on, she said. Besides the STAAR, schools also give students MAP assessments at the beginning, middle and end of each year.

Districts use MAP tests to measure academic growth, but unlike STAAR scores, the results aren’t reported to the state. Because students take MAP assessments three times a year instead of just once, the test can sometimes give a more complete picture of how that student is doing, she said. Teachers are also in a better position to discuss the whole child in a way that tests can’t capture, she said.

Parents release balloons to mourn reading scores

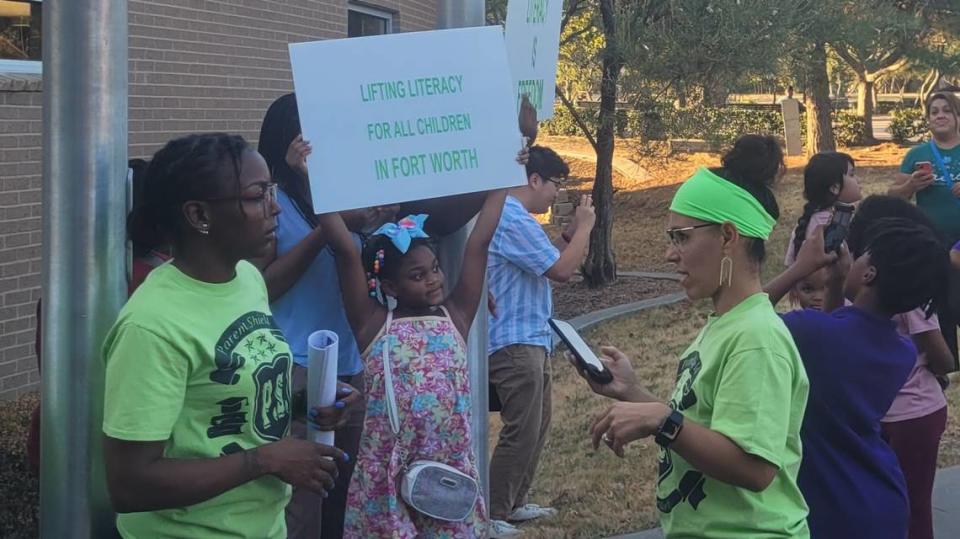

On the evening of Sept. 7, a few dozen parents, many with their kids in tow, gathered on the sidewalk outside the Fort Worth Public Library’s Ella Mae Shamblee branch, in the city’s Historic Southside neighborhood. Some held signs with slogans like “Literacy is Freedom” and “Our Kids Matter.”

As cars drove past on Evans Avenue, organizers passed out balloons to people in the crowd. Trenace Dorsey-Hollins, director of Parent Shield Fort Worth, told the crowd that parents have to demand better for kids who are falling through the cracks. During the group’s literacy clinics held over the summer, 70% of parents who attended told organizers that they thought their kids were reading on grade level. But when school staff members gave kids reading assessments, the results mirrored what state test scores show, she said.

“Our children are not being taught to read, and reading is true freedom,” she said.

Before the crowd released the balloons, Dorsey-Hollins reminded parents in the crowd that, by showing up, they were signing up to be advocates for literacy. She asked them to remember students who have passed through the school system without getting an opportunity to become proficient readers, and hold fast to hope for students in the future. Then, she counted to three, and the crowd let go of the balloons. They sailed up above rooftops, drifting north over nearby Evans Avenue Plaza before rising out of sight.

The rally fell the evening before International Literacy Day. Dorsey-Hollins said the group released balloons as a show of grief, but also to symbolize hope for the future. Even as they mourn opportunities that have been lost, parents hope to see reading scores rise over the next few years, just like the balloons rose above the library’s roof and into the sky, she said.

Fort Worth ISD school board member Wallace Bridges, who represents Historic Southside, said he was proud to see the turnout. Speaking to a crowd of mostly Black and Hispanic parents, Bridges said there’s a perception that communities of color don’t care about what’s happening in education. It’s important for parents in those communities to send a message that they do care and they want to see better, he said.

Bridges said he hopes the event can mark a starting point for the entire city to rally around improving literacy. It’s a big problem that requires everyone’s help, he said — business leaders, church leaders and leaders in the broader community all have a role to play.

There’s a growing understanding across the city that reading outcomes need to be improved, and that it will take a broad community commitment to make it happen, said Elizabeth Brands, executive director of the literacy advocacy group Read Fort Worth. The group works with about 20 community partners, including Fort Worth ISD, the city of Fort Worth and a number of youth organizations, to improve third-grade reading rates in the district.

Among other programs, the organization held learning programs over the summer at more than 100 sites across the city. Those programs helped participating kids stave off the learning loss that many students experience over the summer, Brands said. Literacy assessments showed that 91% of the students who participated either maintained or improved their reading skills.

The partnerships that Read Fort Worth has built with other community organizations are a critical piece of the path forward, Brands said. Sub-par literacy rates are a whole community problem, and it takes the skills and perspectives of the entire community to fix them, she said.

“These are complex issues that we’re trying to solve, and there isn’t going to be one silver bullet to make sure that we’re seeing the literacy outcomes that we really desire for a thriving and vibrant community,” she said.

Mismatch leaves parents unaware when kids are struggling

Brent Beasley, president of the Fort Worth Education Partnership, said the mismatch between students’ report card grades and how they do on state tests can leave parents with the mistaken impression that their kids don’t need any extra help. When parents see good grades on their kids’ report cards and don’t hear about any problems at school from teachers, most generally assume that everything is fine, he said, but that isn’t always the case.

“What we’re learning is getting As and Bs doesn’t necessarily mean that kids are learning their ABCs,” he said.

Beasley said parents need better access to information about how their kids are doing in school. Most districts in the Fort Worth area don’t include either STAAR or MAP test results in their parent portals, he said. The Texas Education Agency has a website where parents can look up how their kids performed on the state test, with detailed information about the particular kinds of questions they missed. But the login process is complicated, requiring a six-digit access code that parents have to get from their kids’ schools. That leaves many families without access to any information about how their kids are doing other than their report cards, he said.

Fort Worth reading grade mismatch mirrors national trends

The mismatch between Fort Worth parents’ impressions of how their kids are doing and how they perform on tests is in line with national trends, according to a recent study. In surveys fielded in March, 92% of parents across the country told pollsters they were confident their child was reading at or above grade level, according to a report from the national education advocacy group Learning Heroes. In the same survey, eight in 10 parents said their children brought home all As or Bs on their report cards.

But according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, sometimes known as the Nation’s Report Card, only about a third of fourth-graders across the country were either proficient or advanced in reading in 2022.

Cindi Williams, co-founder of Learning Heroes, said the group has studied the mindsets of parents of school-aged children for decades. Over time, the results have been essentially the same, she said: More than nine out of 10 parents think their kids are performing at grade level or better both in reading and math. Those results bear out across all racial and ethnic groups and income levels, in all parts of the United States, she said.

“The disconnect is consistent across the country,” Williams said.

Grades can be a helpful way for parents to see how their kids are doing in school in a general way, Williams said. The problem is that they take into account many factors besides academic performance, she said. Other things, such as whether a student participates in class discussions and whether they get their homework done on time, can influence their grades, but don’t necessarily have anything to do with whether they’ve mastered the knowledge and skills they should have that year, she said.

A big part of the disconnect comes from how much emphasis parents place on report cards as a way of understanding how the kids are doing, Williams said. In surveys and conversations with parents, the group found that parents generally think report cards are the single best way to know how the kids are performing, she said.

But teachers placed far less emphasis on the importance of report cards. When the group polled educators, they generally said the most important way for parents to know how their kids were doing in school is through regular communication with their child’s teacher. Parents identified those conversations as the least important tool, behind other factors, such as graded tests and quizzes and their child’s mood or body language. Teachers have access to a number of tools that they can use to see how students are doing day to day, Williams said, but if parents don’t talk to teachers regularly, they don’t get that information until report card time.

Parents have to be good problem solvers, she said, so when they find out their kids are underperforming in school, they’re usually quick to help. But parents can’t solve a problem they don’t know they have, she said. If parents don’t know they should be talking to their child’s teacher regularly, the public education system gives them no other way to get regular updates on how the kids are doing compared to grade-level standards, she said. So kids could be behind for months before their parents know there’s a problem, she said.

‘Passing the babies along’

Mire, the Rocketship Dennis Dunkins mom, said the knowledge that her daughter was behind last year helped her walk into this school year ready to help. She met with Malaysia’s teacher before the school year started to talk about a plan for getting her caught up, she said.

About a month into the school year, Mire said she could already see the beginnings of progress. Malaysia’s teacher pulls her aside for extra help anytime they have a reading test coming up, and Mire makes the point to read with her daughter every day at home.

Reflecting on the reading assessment Malaysia took over the summer, Mire said the results left her alarmed. If she had no idea her daughter was so far behind, she wonders how many parents are in the same situation.

“Our kids are behind,” she said. “And they just passing the babies along.”

Disclaimer: The Sid W. Richardson Foundation is a supporter of the Star-Telegram’s education coverage. Editorial decisions are made independently.