State workers protest at California state Capitol to demand pay raises amid SEIU bargaining

Hundreds of California state workers descended Thursday on the state Capitol to protest what they call an “offensive” and “unfair” contract offer from the state.

The workers, who are represented by Service Employees International Union Local 1000, dressed in all black to “mourn the death of California’s middle class” and carried signs that read “Respect Us.” Local 1000 represents about 100,000 workers in jobs as diverse as prison librarians, janitorial staff and educators at California’s schools for the deaf and blind.

“There was a time when we were middle class,” said Bill Hall, Local 1000’s board chair, in a speech to the demonstrators before they entered the building.

The union is currently bargaining for a new three-year contract — their current deal expires Friday.

Originally, the union proposed an unprecedented 30% pay raise over the life of a three-year contract. (Their current contract awarded a 7% raise over the course of three-and-a-half years.)

Facing an estimated $32 billion budget shortfall, the state offered 2% raises each year for a total of 6% overall — an offer that members of the bargaining team called “insulting.” According to a Wednesday bargaining update shared with union members and obtained by The Sacramento Bee, Local 1000’s bargaining team then lowered their ask slightly to 26%, which the state also rejected.

Some state workers have said their government salaries fail to cover basic needs, such as rent, food and utilities.

Krystal Coles, 42, joined the Department of Housing and Community Development three years ago so she could receive state worker benefits, such as a pension and health care. But the single mom of two teenagers says she’s “barely making it” financially. If it weren’t for her side hustles as an Amazon delivery driver and freelance photographer, Coles said she wouldn’t be able to afford basic expenses like rent, utilities and food. She’s found herself in food banks “several times” since becoming a state worker.

“I can’t even pay my credit cards right now,” Coles said. “They’re maxed out, and those are the last things I pay. I don’t care about that. I just need to keep my lights on and everything else.”

A study released in March, which was commissioned by Local 1000 and conducted by the UC Berkeley Labor Center, found that many Local 1000 members were struggling financially, particularly women, Black and Latino employees. The study found that nearly 70% of the union’s members fail to earn a wage high enough to support themselves and at least one child.

Once the protesters snaked their way through security and entered the rotunda, they walked quietly in a circle while holding their signs, some with fists raised in the air. The crowd let out a collective “Shhh!” as one voice shouted, “Who has the power? We have the power!”

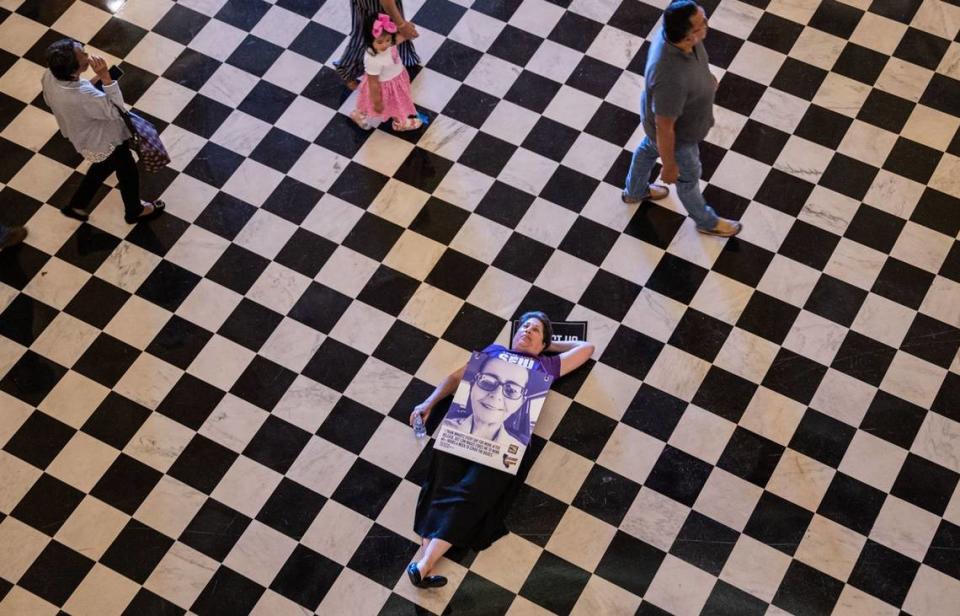

As the demonstrators moved out of the Capitol and over to the swing space, Francesca Wander laid herself down on the floor of the rotunda and refused to move, even when officers with the California Highway Patrol asked her to. As an affordable housing specialist with HCD, Wander said her current pay doesn’t match her workload. The 65-year-old said she can’t afford to retire now, but she doesn’t know if she’ll last five more years, at which point she’d max out her Social Security benefits.

“I’m not moving unless they want to move me,” Wander said as she lay on the floor. Tourists gave her curious looks as they snapped photos of the rotunda with their phones.

About 100 workers with Child Care Providers United, whose contract also expires on Friday, showed their support for Local 1000 by joining the demonstration on Thursday. Patricia Moran, a child care provider from San Jose, said she came out to support state workers because they share similar struggles to put food on the table and cover other basic living expenses.

“We are supporting them, because they supported us,” Moran said. “A lot of those workers — we are the ones who take care of their children in order that they can go to work.”

Although most of Local 1000’s contract will remain in effect until a new agreement is reached, union members who are enrolled in CalPERS health insurance plans will lose their monthly $260 health care stipend after Friday — a loss that some members characterize as an additional pay cut. Local 1000 proposed a new $320 monthly payment, but the state rejected the idea, according to the bargaining update. Instead, the state countered with a three-tiered stipend — $30, $70 or $140 — depending on the employee’s chosen health plan. The state also rejected Local 1000’s request for a paid Juneteenth holiday, according to the bargaining update.

The union points to high inflation as a justification for their proposed pay increase even if past state deficits have necessitated cuts in spending.

State worker raises generally kept pace with inflation prior to 2008, according to a Sacramento Bee analysis of data from the California Department of Human Resources. But after the Great Recession hit, workers in most bargaining units saw their pay stagnate and their purchasing power fall. Some workers were just starting to see their contract raises catch up with inflation when the COVID-19 pandemic hit and consumer prices soared to historic levels.

The last time the state faced a large deficit in 2020, Newsom used a furlough-like program to cut state worker pay for a year, giving public employees two days of paid leave per month in exchange.