The Station fire changed how we view fire safety. But has prevention actually improved?

Fire officials across Rhode Island agree that the state is considerably safer than it was over 20 years ago, thanks to sweeping changes made in the wake of The Station nightclub fire.

But one thing hasn’t changed: In many communities, the crucial task of inspecting buildings in search of potentially life-threatening fire hazards falls to just one person.

In rural towns and villages, that individual may have another full-time job, or even be an unpaid volunteer. In urban areas, high turnover means that fire marshals rarely stick around long enough to learn all the nuances of the code.

More: Should PTSD qualify for injured-on-duty status? Firefighter and RI state Rep. talks trauma

“It's always a revolving door, and there's generally never enough staff on the local level to do what really needs to get done,” said state Fire Marshal Timothy McLaughlin, who trains the firefighters who conduct inspections in their towns. “I mean, they do a really good job with what they have, for sure. We're very fortunate, we’ve got a lot of really good fire marshals in the state of Rhode Island. But most of the assets are on the suppression side and not on the fire prevention side.”

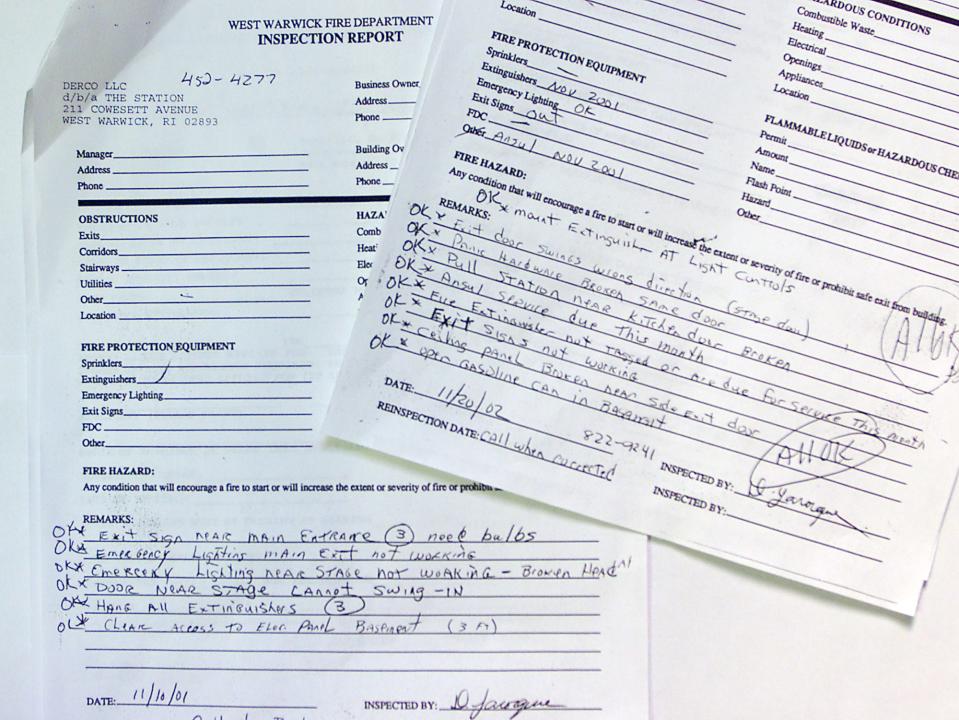

The Station nightclub fire — one of the worst tragedies in Rhode Island history — was the result of multiple failures that added up to devastating consequences. There was the band’s decision to shoot off pyrotechnics. The West Warwick nightclub’s decision to muffle sound by covering the walls with highly flammable foam, which went unaddressed in reports by the local fire inspector. And the fact that 462 people were packed inside, exceeding The Station’s legal capacity. The fire killed 100 and left more than 200 injured.

It also revealed larger systemic problems: While The Station itself had been inspected regularly, hundreds of bars, nightclubs and other places of assembly across the state hadn’t undergone a thorough fire safety inspection in years and were rife with potential hazards.

For The Station nightclub fire's 20th anniversary on Feb. 20, 2023, The Providence Journal reviewed inspection reports and budget documents from nearly every fire department in Rhode Island and spoke with fire department chiefs and fire marshals across the state.

A theme emerged: Bars and other establishments with liquor licenses are now being inspected by trained fire marshals annually. But a lack of staffing means that inspectors often go years without setting foot in large apartment buildings, hotels or offices, which are considered less of a priority. And in smaller, more rural areas, inspections may not live up to the high standards set on the state level.

After The Station nightclub fire, the state fire marshal's office grew

A few weeks after The Station nightclub fire, The Journal observed that the state fire marshal’s office had been “slowly starved by budget cuts.” In 1991, it had 10 fire inspectors; by 2003, it was down to five.

That trend has been reversed: The office now has 15 fire inspectors, McLaughlin said. And it’s been professionalized.

“It was kind of a dumping ground back in those days,” he said. “I don’t think anybody looked at how important it really was, and I think The Station nightclub fire really opened everybody’s eyes.”

McLaughlin was appointed in 2018 after serving as fire chief in Johnston and, before that, in Pawtucket, where he was chief when The Station fire occurred. He lost two members of his extended family in the fire, “so it’s definitely something that affected me,” he said.

“I was there not on official capacity. I was there as a family member,” he said, recalling what he witnessed at the scene that night. “I saw a whole bunch of stuff there that you don’t want to ever talk about again, but that’s what I brought to this job.”

More: The Station nightclub fire 15 years on: In firefighters' hearts, the disaster isn't over

Who inspects which buildings in Rhode Island, and how often?

In Rhode Island, the state fire marshal’s office is in charge of inspecting facilities that are licensed by the state, such as hospitals, nursing homes, state colleges, daycares and group homes.

Local fire departments handle everything else, including businesses, apartment buildings and K-12 schools.

State law dictates how often certain inspections must take place. For instance, bars and other establishments that serve alcohol must be inspected annually, as part of the liquor license renewal process. Schools, too, must be visited every year.

It’s up to fire departments to decide how often they inspect other types of buildings, such as apartment buildings, which are viewed as less of a “life hazard.”

Workplaces and residential buildings with more than two units must have fire alarms installed and submit quarterly reports to the fire department to confirm that they’re working. But inspectors aren’t required to set foot in the building with any regularity.

There’s also no requirement for fire departments to conduct random spot checks and look for overcrowding or code violations, outside of the annual inspection process.

In many communities, fire marshals “do the inspections they’re required to do by law, and they handle complaints as they come in,” said North Kingstown Fire Chief Scott Kettelle, who is also the president of the Rhode Island Association of Fire Chiefs. But they aren’t necessarily doing anything more than that.

“It’s kind of more reactionary than proactive,” Kettelle said.

Fire prevention is often the first cut to a fire department's budget

Officials say that staffing and budgetary constraints are often to blame. When cities and towns are looking for ways to shrink fire department spending, they tend to hone in on the fire prevention division, McLaughlin said.

“When they cut, those are the jobs they cut,” he said.

Firefighters’ union contracts often include “minimum manpower clauses” that require a fixed number of people to be on duty for every shift, McLaughlin said. That doesn’t leave much room in the budget for fire prevention — which can mean that the department becomes a one-man band, without any support staff.

“It puts a lot of pressure on the local marshal,” McLaughlin said. “There's a lot of pressure, and they get burned out, quite frankly.”

One of the most striking examples is cash-strapped Central Falls, which has a high concentration of old, crowded multifamily homes — but no dedicated full-time fire marshal.

“Fire prevention is a second thought,” said deputy chief Samuel T. Dyman Jr. “They’re worried about putting people on the trucks.”

About five or six members of the Central Falls Fire Department are certified as fire marshals — including Dyman, the department’s second-in-command, who has a long list of other job duties. The rest work full-time as firefighters and get paid overtime to conduct mandatory fire safety inspections on their days off.

“Things slip through the cracks,” Dyman acknowledged. Sometimes, he said, firefighters will respond to a call, discover that the building hasn’t been inspected for five years, and ask themselves, “Are you kidding me? How were we not here?”

The answer, he said, is that “we don’t have enough people to get out there and see all these things.”

After The Station nightclub fire prompted state officials to adopt a more stringent fire code, the number of serious fires seemed to decline, Dyman observed. “Now, we’ve gotten back to the point where, maybe, we’ve been complacent,” he said.

Fire prevention has “taken a back seat” to other priorities, like emergency medical services, Dyman said — even though it’s “the base of everything.”

Even departments with large fire prevention divisions can't keep up

Central Falls is still clawing its way back from bankruptcy, but fire departments in wealthier towns say that they’re short-staffed, too.

Up until five years ago, North Kingstown was doing the “bare minimum,” Kettelle said. The town only had one fire marshal, who didn’t have time to do anything more.

Now that they’ve hired a second fire marshal, the fire prevention division has been working on ensuring that all apartment buildings with more than four units have been inspected. In some cases, several years had passed since someone last stopped by to look for safety hazards, according to Fire Marshal Greg Pariseault.

Up next are industrial buildings. Ideally, the fire department would inspect those annually, Kettelle said. “But it’s just not practical with the amount of staff we have,” he added.

The same is true in Newport, according to Fire Marshal Bob Dufault. Even with five full-time inspectors and one of the largest fire prevention divisions in the state, he said, “we’re never going to get to all the places in Newport.”

One of those five inspectors is dedicated to nightclubs and other places of assembly, which are “an absolute priority,” Dufault said. But it’s also only one facet of the work.

Whenever a fire breaks out, fire marshals are the ones who document the damage and figure out how it started. They’re also in charge of reviewing plans for new construction and inspecting job sites as new buildings go up. A construction boom translates to less time inspecting existing buildings.

Having a tent for a special event requires the fire marshal’s sign-off — and, in Newport, there are thousands of those events per year, Dufault said. Also adding to the workload are short-term rental properties like Airbnbs, which must now register with the city.

More: Short-term rentals are booming with online bookings. Is your town regulating them?

“Last year, because we couldn’t get to every single place, all the ones that had fire alarms and sprinklers that were up to date were approved,” Dufault said. This year, his goal is to make sure that every single one has been inspected.

Inevitably, something ends up falling by the wayside. Dufault points to large hotels like the Marriott as one example. Since they have to have their fire alarms and sprinklers tested on a quarterly basis, the fire department “is less likely to go and inspect those places,” he said. Unless issues arise, they may only conduct a walk-through every five or six years.

Not all fire marshals are performing this kind of triage. In rural communities, there are hardly any businesses to worry about — let alone apartment buildings.

“I pretty much get to everything that needs to be done,” said Susan Hawksley, the fire marshal for Exeter’s two volunteer fire departments.

But those smaller communities sometimes have their own problems.

Journal investigation found spots where liquor licenses were renewed despite documented code deficiencies

In theory, the quality of fire safety inspections shouldn’t vary from town to town. With a few minor exceptions, they’re all carried out by fire department personnel who have been certified as assistant deputy state fire marshals and received the exact same training from the state fire marshal’s office.

The Providence Journal asked each fire department in the state to provide several years’ worth of reports from establishments that have liquor licenses and must be inspected every year.

Most had no obvious red flags, and some were incredibly detailed — the Bristol Fire Department, for instance, included photographs documenting every deficiency that inspectors spotted.

But in some smaller communities, the reports raised questions about whether safety hazards were actually getting fixed.

One glaring example involved the Pinewood Pub, a pizza parlor and bar in Glocester.

Each of the inspection reports that Chepachet Fire Chief Dennis Huestis authored between 2019 and 2022 listed the exact same five deficiencies — word for word. (One example: “Emergency light/exit sign not illuminating under battery power. Unit on the first floor, front kitchen exit door.”) All that changed was the date.

Huestis acknowledged that his reports were “usually cut and paste from the year before.” But he said that he really had witnessed the same exact problems at the Pinewood Pub every year, and that, in each case, they’d been corrected when he returned for a follow-up inspection. (Pinewood Pub did not return calls and emails from The Journal.)

Records show, however, that Huestis emailed Glocester’s town clerk on Nov. 29 last year to say that Pinewood Pub was “all set.” That directly contradicted his letter to the business’ owners, stating he had inspected the building on Nov. 29 and found a number of deficiencies that they needed to fix.

Bars aren’t supposed to have their liquor licenses renewed if a fire marshal has observed outstanding deficiencies. But since Huestis gave them the go-ahead, Glocester renewed the Pinewood Pub’s liquor license the following day.

“That should never happen,” said McLaughlin, the state fire marshal. “Absolutely not.”

Asked if he typically signed off on liquor license renewals before ensuring that the problems he’d identified had been fixed, Huestis said, “It’s what we’ve been doing for quite a while.” However, he added, “It’s got to be changed. The way we do things, it’s definitely got to be changed around.”

Occasionally, small volunteer fire departments find themselves without a certified fire marshal, so the state fire marshal’s office will step in to conduct mandatory inspections.

Last June, state inspectors discovered that the carousel in Misquamicut lacked a fire alarm system, as did several dorms that house employees on Block Island.

More: The housing crisis is crippling Block Island. Is this the future for the rest of RI?

Asked why those problems hadn’t been discovered before, McLaughlin said that the state fire marshal’s office has been ramping up its inspections in those areas. (The state fire marshal’s office has been responsible for Misquamicut for the last five years, he said, and has handled Block Island inspections for the last several years.) Sometimes, it takes a new inspector coming in to see what a previous inspector had missed, he added.

“Sometimes you find out, once they're not here anymore and they've moved on, that maybe they didn't do what they were supposed to do,” McLaughlin said.

Rhode Island has 39 cities and towns, but 64 local fire departments

Rhode Island has 39 cities and towns, and, at last count, 64 local fire departments. And that’s not counting the dedicated fire and rescue squads for Rhode Island T.F. Green International Airport or Newport’s Navy base.

The northern and western portions of the state are home to a patchwork of independent fire districts and volunteer fire companies, whose jurisdictions often don’t align with municipal boundaries. Burrillville, Coventry, Lincoln, Scituate and Westerly each have four separate fire departments. Foster, Glocester and West Greenwich each count three.

Some of these departments once protected now-defunct mills or are a holdover from a more rural past. As a recent report from the Rhode Island Public Expenditure Council noted, the concept of centralized municipal fire departments didn’t emerge until the middle of the 19th century and was never uniformly adopted.

“Everybody’s got their own little kingdom,” McLaughlin said. “A lot of them are volunteer, so there’s very little cost.”

Some departments, like the Union Fire District in South Kingstown, employ full-time fire marshals. But in volunteer-run departments, the person carrying out fire safety inspections may be doing that work on the side, in exchange for a small stipend — if anything. North Scituate Fire Marshal Karl Petsching, who also conducts inspections for the Chopmist Hill Volunteer Fire Department, doesn’t get paid at all.

Fire inspections in smaller towns can get territorial

Is this decentralized, low-cost approach working? Not according to officials in West Greenwich, who decided last year to hire a townwide fire marshal instead of dealing with three separate volunteer fire departments.

“I’m not going to say the inspections weren’t being done, but they weren’t being done as thoroughly, or weren’t as timely as they should have been,” said Town Administrator Kevin Breene.

Fire marshals for the town’s three volunteer departments often had full-time jobs as firefighters in “big-time departments,” Breene said. That meant they didn’t have much time to conduct inspections on the side and often weren’t available to review plans or visit job sites during standard business hours.

Smoke detector inspections, which are required every time a home is sold, became another source of frustration. Breene said that he routinely received calls from frantic real estate agents who’d repeatedly called to schedule an inspection and couldn’t close on a sale because no one from the fire department was returning their messages.

“That was kind of the straw that broke the camel’s back,” he said.

Theoretically, if the fire marshal for one fire department wasn’t available, someone from the town’s other two departments could have stepped in.

The problem, Breene said, is that “out here in the rural part of the state, it becomes very territorial.”

Fire departments charge for many of the inspections that they conduct, and the plan-review fees for a large development could add up to $60,000 or $70,000, Breene said. No one wanted to give up that source of revenue.

“We kind of tolerated it for a long time,” Breene said. Eventually, he said, the town concluded, “This is getting crazy.”

In October 2022, West Greenwich’s Town Council voted to hire a fire marshal, Mike DeRosa, on a per-diem basis. There wasn’t enough work to justify creating a full-time position, Breene said, but DeRosa comes in a few days a week to review plans and do walk-throughs of local businesses. Revenue from inspections gets split four ways, with an equal share going to the town and each of the fire departments.

“To sum it up, we’ve professionalized the thing,” Breene said.

Fire marshal positions come with high turnover

Communities with municipal fire departments and professional, full-time fire marshals have their own challenge: high turnover.

Often, it feels like as soon as the state fire marshal’s office trains a new inspector and develops a working relationship with them, “they bail,” McLaughlin said.

For firefighters working on the line, being selected to head up fire prevention efforts is a promotion. But in many departments, it’s a steppingstone on the way to becoming an assistant chief or deputy chief — not the place where you’re aiming to spend your career. And it can also mean a cut in pay, since you’re no longer collecting overtime.

“You can watch a guy riding a fire truck making $50,000 a year more than you are, and you're upstairs working your butt off with a lot more responsibility,” McLaughlin said.

“It’s not popular, it’s not fun,” said Dyman, the Central Falls deputy chief. “Everyone signs on to be a firefighter, to be where the action is. This is behind the scenes. This is sitting at a desk doing 9-5.”

The sedentary, desk-bound nature of the job does appeal to firefighters who are just a few years short of retirement and looking for something that will put less stress on their bodies. But that, too, often translates to high turnover.

More: After spending $287K in political donations, firefighters push again for vetoed disability bill

“It’s the job on the way out the door,” said Dufault, who has spent more than a decade in Newport’s fire prevention division. “The problem is that, unfortunately, it takes a very long time to become good at this job and to become knowledgeable in the code.”

Kevin Tuthill, the fire marshal in Narragansett, recalls that he was one of the younger fire marshals in the state when he took the job at age 36. He’s now 40 and can see himself staying in the role for another 15 or 20 years — making him one of the few exceptions to the rule.

“I do think there’s value in having some longevity in the position,” Tuthill said. As he’s gotten to know the buildings in town, he’s started to gain “institutional knowledge” about where there have been issues in the past, and what he needs to keep an eye out for.

Plus, he said, “I’m definitely learning something new every day. … There’s thousands of pages of fire code, and sometimes you get stuck in a book for two to three hours just trying to figure something out. But it’s a great ‘aha’ moment when you find it.”

Tuthill, who has a master’s degree in education, originally planned to become a history teacher and began volunteering as a firefighter while studying at the University of Rhode Island. (He’s now pursuing a doctorate in forensic science — “more fire-related stuff," he said.)

The academic nature of the fire marshal’s job was a natural fit for him, but doesn’t always appeal to younger firefighters who are looking for excitement, he said.

“There’s lots of writing, lots of reports,” he said. “It’s definitely not an easy job, so I get it.”

Providence Fire Department takes to social media to spot violations

Fire marshals throughout the state speak longingly of Providence, which has the largest fire prevention division in the state and enough staff to make random, unannounced visits at bars and monitor social media posts for fire code violations.

The Providence Fire Department typically has between 15 and 20 full-time fire marshals, said Chief Derek Silva. Other municipal fire departments typically have just one or two, at most. (In some communities, like Barrington, the fire chief doubles as the local fire marshal.)

An investigator certified as an assistant deputy state fire marshal is on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week. And because fire prevention is considered a “professional track” and requires a special promotional test, people tend to stay for the duration of their careers and build institutional knowledge, Silva said.

Providence also typically has six to eight part-time inspectors who work “on demand,” Silva said. Those inspectors have full-time jobs on fire trucks or EMS, but have been certified as assistant deputy state fire marshals and will be called up when the fire prevention division can use extra hands — for instance, before the start of the school year, when all the city’s school buildings need to be inspected.

On top of that, firefighters who are on “light duty” for health reasons will often temporarily move to fire prevention, where they assist with tasks like smoke detector inspections that don’t require the same level of training.

All told, Silva said, there are sometimes as many as 30 people in the fire prevention division.

There’s no shortage of work to go around. For starters, Providence has far more bars and nightclubs than any other municipality in the state. Since they can’t be everywhere at once, fire marshals peruse Instagram and TikTok, where revelers often inadvertently document fire code violations.

“Social media is one of the main ways we find out about code infractions,” Silva said.

Among the most common: placing lit sparklers in champagne bottles at clubs. “Those sparklers are the same thing that started The Station nightclub fire, the gerbs,” said Lt. John Lima, referring to the type of firework that shoots a fountain of sparks. “It was just bigger, but it’s the same thing. They’re shooting them at the ceiling and I’m like, ‘Guys, you can’t do this, please.’”

Problems also get flagged by the Providence Police Department’s liquor squad, which goes out at night to check on bars and nightclubs and keeps an eye out for establishments that are over capacity or have blocked exits. “They’ll call me at night, send me pictures on the phone, and say ‘Hey, does this look right?’” Lima said. If there’s an immediate threat to life and safety, “they’ll shut them down that night.”

As in other parts of the state, apartment buildings and workplaces in Providence don’t get quite as much attention. The fire prevention division recently inspected all apartment buildings with 20 units or more —“something that probably had not been done in five, six, seven years,” Silva said.

Smaller residential buildings typically only get inspected when they’re sold, if there’s a complaint or an incident, or if the city stops receiving quarterly fire alarm reports. The same is true of office buildings, Silva said.

Would he like more staff? Of course. But there are budgetary constraints, Silva said.

“We make it work,” he said. “It’s not like there’s a glaring area that we’re not looking at that we should be. Everything’s getting covered.”

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: How did The Station nightclub fire change safety in RI and is it better?