'Stay mad as hell,' says last surviving author of famous report on 1967 riots

WASHINGTON — In 1967, the nation was consumed in protests over racism and police brutality, and Sen. Fred Harris watched from Washington, D.C., as Newark, N.J., and Detroit burned.

Despite that painful history, the retired 89-year-old, a Democrat who represented Oklahoma, is hopeful. As the last living member of a famous commission on the civil unrest of 1967, he believes that today’s protests are indicative of a broader awareness in American society and could finally lead to lasting improvement in race relations.

“These protests are larger,” Harris told Yahoo News from his home in New Mexico, where he has lived for decades, having until recently served as a political science professor at the state’s flagship university. “They are more widespread, they’re multiracial, they’re longer-lasting.” He adds that in comparison to 1967, “there is less violence — though too much of it.”

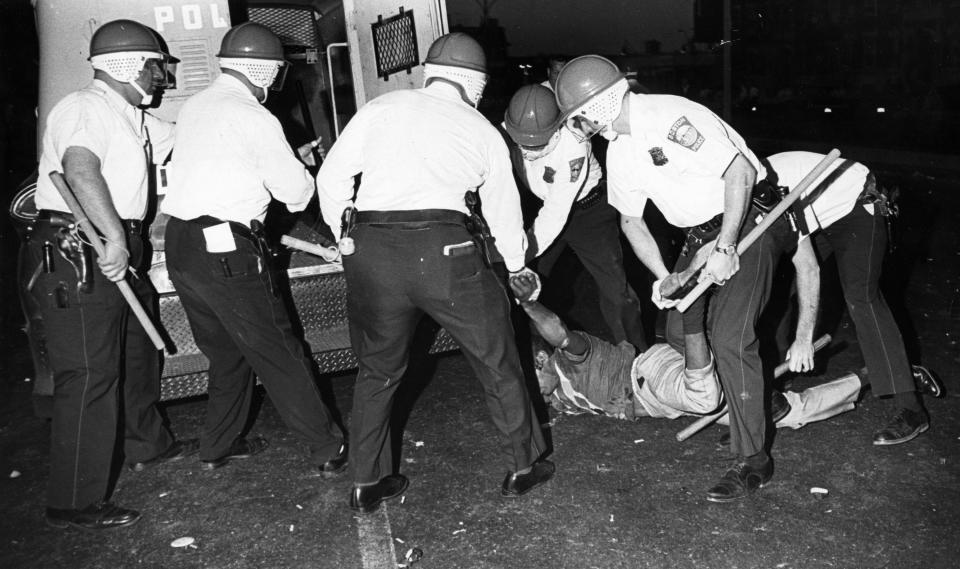

What is commonly known as the “long, hot summer” of 1967 saw African-American communities across the nation explode in anger over police brutality, lack of job opportunity and other forms of discrimination. By summer’s end, there had been a total of 164 disturbances so far that year. While the causes were disparate, they broadly expressed disenchantment on the part of African-Americans about what they could expect from society at large.

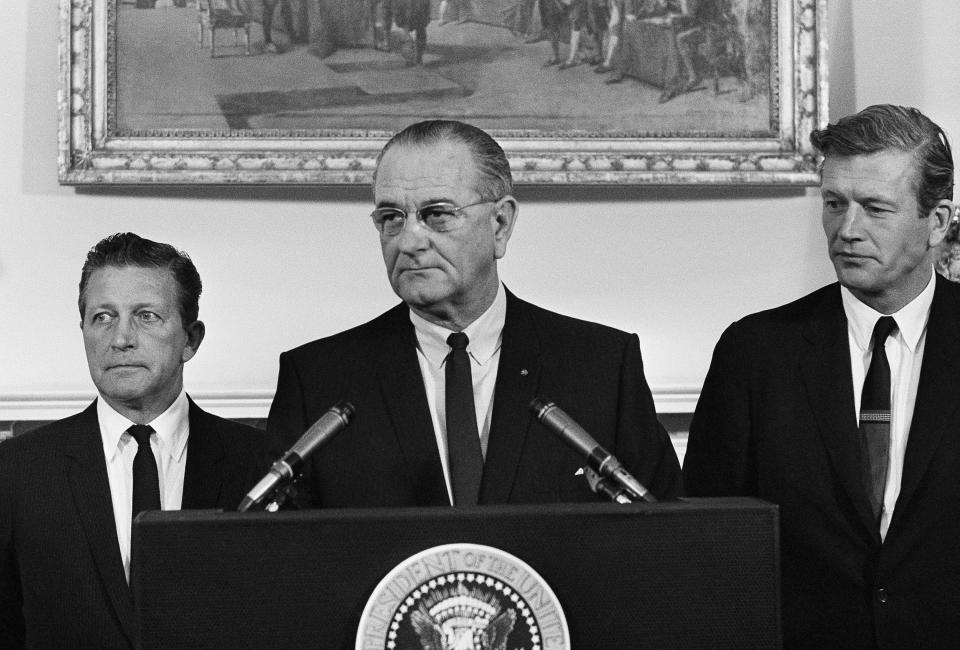

President Lyndon Johnson was personally stung and stunned by the civil unrest, which he saw as a rebuke of his own efforts at racial equality. Early in his presidency, he had signed the Voting Rights and Civil Rights acts, both landmark achievements. But there were, it was evident, problems that the legislation could not fix.

On July 27, 1967, Johnson appointed the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, to be led by Gov. Otto Kerner Jr. of Illinois and Mayor John Lindsay of New York. There were 12 members, from NAACP head Roy Wilkins to Atlanta Police Chief Herbert Jenkins.

Eleven of them have died. Harris alone remains.

And now the country is burning again. “I’m sick at heart and grief-stricken and mad as hell,” Harris says of the protests that have followed the May 25 killing of unarmed black civilian George Floyd by several white police officers in Minneapolis.

The committee appointed in 1967 is generally known by its chairman’s name, but Kerner was not among its central figures. Much of the work was done by Harris, the son of white sharecroppers who was then serving as a liberal senator from Oklahoma, and Lindsay, the photogenic mayor who entertained presidential dreams. (Though a Republican, Lindsay would be a progressive by today’s standards; he eventually switched parties.)

The report published in 1968 by the Kerner Commission remains one of the most prescient documents in recent American history, an indictment of discrimination and injustice that remains true for many Americans today, especially for those who are neither white nor well-off. With remarkable bluntness, the document places the plight of black Americans at the feet of their white counterparts.

Decades before demonstrators filled streets in New York City and Washington, D.C., with placards decrying “white silence,” the Kerner Report warned that racism had created in the inner cities “a destructive environment totally unknown to most white Americans.”

The historian Stephen Gillon, who wrote a book on the Kerner Commission, called its report “the last full-throated declaration that the federal government should play a leading role in solving deeply embedded problems such as racism and poverty.”

Indeed, the report’s language — at times aspirational, but not infrequently confrontational — is almost difficult to fathom for anyone accustomed to the careful bureaucratese of federal documents.

“Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal,” the report’s widely cited introduction says. That same introduction urges the U.S. “to turn with all the purpose at our command to the major unfinished business of this nation.”

The report was a survey of the 23 cities that had undergone convulsions of violence months before. Police brutality was at the center of many of the conflagrations, as it has been today in Minneapolis and many other places before that.

With a sensitivity that seems striking, the report warns of the suspicion with which many African-Americans viewed law enforcement. “The police are not merely a ‘spark’ factor,” the Kerner Commission warned. “To some Negroes police have come to symbolize white power, white racism and white repression.”

Members of the commission toured the cities devastated by civil unrest. They came away with conclusions that were nuanced and, at times, counterintuitive. “What the rioters appeared to be seeking was fuller participation in the social order and the material benefits enjoyed by the majority of American citizens,” the report says at one point. “Rather than rejecting the American system, they were anxious to obtain a place for themselves in it.”

Throughout, a sense of two separate nations uneasily coexisting within the same border pervades. That divide remains all too real for many. Some observers in recent days have highlighted a double standard in how President Trump praised the armed right-wing (and almost uniformly white) protesters demonstrating against coronavirus lockdown restrictions but condemned the Floyd protesters as “thugs.” That disparity led Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell to conclude in a recent piece that there is “the white America, where citizens can expect to be served and protected — and the black America, where they can’t.”

That brought her to where Harris and his Kerner peers have been since 1968, lamenting racial divisions that demand reconciliation.

The difference, Harris says, is in the awareness of the public at large. The Kerner Report makes clear that most white Americans did not know what life was like in the inner cities — and hence could not understand the reasons behind the protests.

The prescience of the Kerner Report has continued to haunt sociologists and political scientists who worry that we have forgotten it, to our detriment. “The 1968 Kerner Commission Got It Right, But Nobody Listened” went the headline of a Smithsonian Magazine story by historian Alice George published two years ago.

Princeton political scientist Julian Zelizer turned to the Kerner Report after the killings by white police officers of several black men, including Eric Garner in New York City and Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. “I honestly had not read it closely in a while,” Zelizer told Yahoo News.

“It holds,” he said of the 52-year-old report. Zelizer was especially struck by its frank addressing of white racism as a cause of the unrest.

Conservative critics say that both Johnson’s Great Society and the Kerner Commission called for too much federal spending and government control.

Politically, the unrest of the late 1960s proved a boon for Richard Nixon, who appealed to white Americans terrified by the images of burning cities. “Just as we cannot have progress without order, we cannot have order without progress,” he said as he accepted the Republican nomination for the presidency in 1968.

Trump has made the same point with less nuance, sending tweets that say simply “LAW & ORDER” and “SILENT MAJORITY,” the latter a widely given name to the white supporters who propelled Nixon into the White House in 1968.

Then, as now, some wanted to portray the unrest as the work of opportunistic looters, dismissing the concerns of African-Americans who saw themselves as victims of systemic racism and excessive police force. Harris was not among the skeptics then, and he is not among the skeptics today.

“We don’t need to militarize,” he says. “We need to communitize.”

Princeton’s Zelizer thinks the Nixon playbook will be difficult for Trump to execute, since he is the incumbent, whereas Nixon was running against eight years of Democratic rule. “He’s the one in charge,” he told Yahoo News. “The breakdown in order, the chaos, work against him.” Then again, he believes that Trump could “reenergize and solidify” his base, which is made up of nonurban white voters more likely than other groups to view the ongoing protests with suspicion.

Even as others have either forgotten the Kerner Commission Report or dismissed its idealistic conclusions, Harris has spent decades insisting that both the diagnosis it delivered and the cures it proposed remain relevant, especially since racial strife and inequality remain persistent.

He says the progress of the 1960s “stopped — and then reversed,” largely as the work of a conservative movement invigorated by the ascendancy of Ronald Reagan.

Though Zelizer deplores the violence on display nightly on television screens, he says it is hardly the main thrust of today’s protests, praising the “passion” and “determination” of the people gathering before the White House, across New York City and in many other cities.

Whether that determination translates into anything lasting remains to be seen.

“We’ve studied this problem to death,” Harris says. “We know what needs to be done.”

The solutions he lists, including fair housing, incoming equality and urgent improvement of schools, are all Great Society proposals. They have been roundly rejected by generations of conservatives, as well as some next-generation liberals. At the same time, a younger generation of progressives appears to embrace these abandoned solutions of yesteryear.

“People want to do this,” he says. “People are far ahead of politicians.”

Such reforms cannot wait, Harris believes, because the fire next time could be all-consuming. He urges people to “stay mad as hell” and, when the time comes in November, take part in the democratic process and vote.

“This may be our last chance,” he warns.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: