Steck's stand: How a Southport woman was inspired to champion civil rights

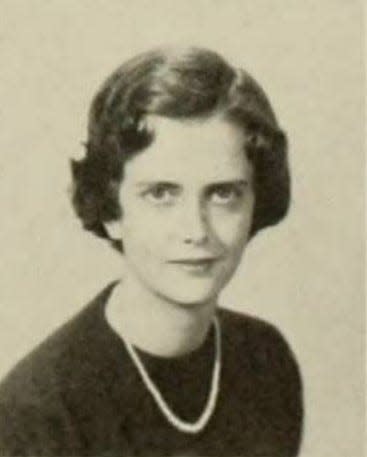

If you lived in North Carolina in 2013, you probably have seen Musette Steck.

Her image was plastered across the front page of many newspapers, including two of the state’s largest in The News & Observer and The Charlotte Observer.

While the Associated Press photo didn’t include her name in the caption, many recognized Steck as the woman whose hands are being zip-tied behind her back by a Raleigh police officer.

“I had people calling me from Edenton, saying, ‘Hey Musette, have you been down in Raleigh,’ and somebody called me from the mountains,” she recalled.

Steck, then 75 years old, was arrested at the State Capitol during the Moral Monday protests. For those who know her well, that’s no surprise. Steck has long advocated for social justice and educated people about North Carolina and its history.

Her work as a historian in Southport has earned her local recognition, including the prestigious Walter Welsh Award in 2014, which is given annually to someone who promotes racial harmony, tolerance and understanding.

Steck, a white woman, also served as Grand Marshal of Southport’s Juneteenth Parade and festivities one year.

But her pursuit of social justice and her love of history began long before she arrived in Brunswick County.

Seeing injustice

Steck’s road to advocacy began in Enfield, North Carolina — a predominantly Black community — during segregation.

When she was very young, she recalls her childhood best friends often dared her to drink from a water fountain that said “colored.” Though she was always told not to drink from it, she didn't understand why.

One day the temptation became too great, and she took a drink from the forbidden fountain.

“I was so disappointed because it wasn’t colored; it was just plain water,” she said. “I thought it was going to be grape or orange or something.”

As Steck became older, she found out the true meaning of the separate fountain. It didn’t sit well with her, and she began questioning injustice when she saw it.

Perhaps her most vivid recollection occurred when she was about 8 or 9 years old. She was standing in the Roses discount store in Enfield looking at the baby dolls. As she perused the selection, she only saw white faces. Steck walked the few blocks home to meet her parents for lunch and asked them why there were no Black baby dolls at the store. They told her to ask the manager, so she did.

“Her answer to me was, 'Well the little colored' — that was the word they used,” she said, shaking her head at the memory. “She said, ‘When the colored children grow up, they will probably take care of white babies,’ and that didn’t make sense to me. That’s when I first realized that things were not fair. So since then, in the ways that I could, I just try to put myself where I’d want to be.”

She credits her “Black awareness” to her parents who were forward-thinking people. Her mother was chair of the Halifax County School Board when the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka case was being heard. At the time, Steck said Halifax County had 37 Black schools, 11 white schools, and three Indian schools.

“Every Black principal came to our house — to talk about their jobs, I’m sure — and I’d walk home from school, and there’d be a Black man sitting in the living room, and that was not usual,” she explained.

One day, Steck was coming home from school and met one of the men outside the house.

“He knocked on the front door and started down the steps, and I said, ‘No, come on in,’ and so, he did,” she said.

When her mother passed away in 1997, Steck found out many of the neighbors thought it was scandalous she had invited the man to walk through the front door into the home.

But she didn’t think anything of it.

“I just grew up with people accepting people as people,” she said.

Taking a stand, and a seat

Steck attended Duke University. That was eye-opening for a young woman who had grown up in a very rural area and was one of only 27 in her graduating class.

“When I went to college, I’d never written a term paper,” she said. “I’d not even written what we would call essays. I don’t know how I made it except I had confidence. I didn’t have enough sense to know I really was in over my head.”

In addition to learning to write term papers, Steck had a bit of fun. A few days before Duke was to play its Tobacco Road rival in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, she awoke to find “UNC” painted across the glass panels of the new women’s dormitory building. After seeing the building desecrated with those large, baby blue letters, Steck and three of her sorority sisters decided to take action.

Duke University’s pep board had distributed posters that said, “Do you recognize Sonny Jurgensen? You should. He’s going to help us beat Carolina.” Jurgensen, who grew up in Wilmington and played at New Hanover High School, played football for Duke in the 1950s and went on to have an NFL career with the Philadelphia Eagles and the Washington Redskins (now Commanders).

Steck and her friends gathered the posters and drove over to UNC where they plastered them all over campus. As they were getting ready to leave, Steck was apprehended by campus security.

“I hear a man say, ‘Halt,’ and I looked behind me and saw this man running or limping,” she recalled. “He couldn’t run, and I didn’t think it was kosher to keep running, so I stopped, and he wanted to know who I was and where I was from.”

Duke University's students had been warned not to get into trouble on another college campus, and while she did have some explaining to do, she was eventually let off the hook because it was just a prank.

The event earned her a nod from the student body president at graduation.

“She was acknowledging people for being a Rhodes Scholar and for being hired by the Philadelphia Symphony — and for Musette Steck for being apprehended on Carolina’s campus,” Steck said.

Continuing a life of advocacy

After graduating from Duke in 1959, Steck married and moved to Greensboro where she raised her children, eventually returned to school and earned a master’s degree in Public Administration.

In Greensboro, she became a member of the NAACP and helped raise money for the organization now known as the United Fund, which provides scholarships for Black students.

Steck also sought political office for the first time, which wasn't surprising given her strong convictions and her family's political history. Her grandfather was Gov. William Walton Kitchin, an attorney who served as the 52nd governor of North Carolina, and her great-uncle was U.S. Rep. Claude Kitchin.

Steck ran for Guilford County commissioner twice, but unlike her ancestors, she was defeated both times.

In 1997, Steck relocated to Brunswick County in the budding town of St. James. There she finally got her opportunity to serve in politics. She was elected as a member of the founding town council. However, her political career was short-lived. After her first term, she heard something that took her interests down a different path, so she decided not to seek re-election.

“My next-door neighbor had a friend who had just moved in, and she said to her, ‘I didn’t know white people were Baptist,’ and I decided I might not be able to make laws for people, but I could teach them history,” she said.

The move led Steck to pursue a position teaching North Carolina history at Brunswick Community College. She also became active with the Southport Historical Society, later serving as its president and becoming a lifetime member. Her work as a historian took her across the county, and she helped author a book on Brunswick County’s architecture and served on a county committee documenting Brunswick’s cemeteries.

Steck also found a group of like-minded individuals who began using their voices to advocate for political causes. In July 2013, she and three other local women traveled to Raleigh during the Moral Monday protests where Steck was arrested for civil disobedience, an experience she said was "thrilling." The event was captured by an Associated Press photographer and splashed across newspapers’ front pages.

Unlike the incident at UNC, this was an arrest. Steck was handcuffed and loaded into the back of a law enforcement vehicle. She also had to be fingerprinted and have her mugshot taken. She recalled stepping up to the photographer was a bit awkward.

“The gave me a sign with my numbers on it, and I started to smile, and I thought, ‘Fool, this is not Olan Mills for the church directory,’” she said.

Though she was booked and later had to appear in court on her charges, some criticized her for her politics — one man even accused her of pulling off a publicity stunt. Fortunately, many others congratulated her standing up for convictions.

“I had so many people afterward tell me, ‘I wish I had enough nerve,’ but I’d tell ‘em it doesn’t take nerve,” she explained. “You go with people you know. When you are not going to be hurt, and you have everything that you are wanting other people to have, how can you not do it?”

Donnie Joyner considers Steck a close friend and has worked with her on many projects, including a walk to unite their two churches. Joyner, a member of Mt. Carmel AME Church in Southport, recalled Steck had been working on something to recognize the shared history of Mt. Carmel and Trinity United Methodist Church for several years.

Joyner helped Steck with the project, and they brought the two congregations together in 2014. While the event may have been the first time the two churches' congregations worshipped together, it wasn't the first time Steck had been inside Mt. Carmel. In fact, Joyner said frequently visits Southport's Black churches for special services and gospel events.

"I don't think there's a Black church in Southport that she hasn't visited more than once," he said.

But he said her support goes beyond just attending the occasional service or event. Joyner recalled when Mt. Carmel lost its steeple during Hurricane Florence and sustained significant water damage, Steck was the first one to "drop a thousand dollars."

Then in 2015, Steck traveled with Joyner to Charleston, South Carolina, to attend the funeral of the Rev. Clementa C. Pinckney, pastor of Mother Emanuel A.M.E. Church. Pinckney and eight members of his congregation were murdered by a lone gunman in a racially-motivated hate crime.

Joyner said he asked several of Mt. Carmel's church members to attend the funeral, but nearly all were working.

"The only person I could get to go with me was Musette," he said. "So, we represented Southport."

Joyner said they actually were admitted inside the church for the funeral and at one point, Steck was dancing in the aisles with the ushers and seemed to feel right at home.

"That's just Musette," he said. "She doesn't just talk the talk; she walks the walk. She's the real deal."

Steck has never been one to back down from a challenge, and thanks to her volunteer spirit and sense of activism, she has been asked to take on jobs, whether it be in her church or a community organization. Some would approach her and note the job “didn’t require much,” which caused Steck to decline those positions and encourage them to offer it someone who wanted a job that didn’t require much work.

“I want to be able to do something — to make some progress, some effort,” she said. “So, I guess that’s why God gave me a hard head and a strong heart.”

Still championing causes

Now in her mid-80s, Steck is slowing down, but only a little. A longtime member of the Southport Historical Society, she still participates in their programs, including two of the programs she helped establish, “Living Voices of the Past” and “Tuesday Talks.”

Steck was recently appointed by the Southport Board of Aldermen to serve on the city’s cemetery committee, and she’s still working to educate others about local history however she can.

The Tuesday before Thanksgiving, Steck was walking through Old Smithville Burying Ground when a man approached her and asked for her help locating a tombstone. Although he didn’t realize it initially, he was talking to an expert on local history and cemeteries.

From 2007: Old Smithville Burying Ground's upkeep depends on volunteers

What to know: Southport cemetery oldest in Brunswick County

The man was looking for the angel monument featured in the film “A Walk to Remember.”

“Well, we don’t have any angels here,” Steck told him. She noted it must have been created for the film. As a local historian, Steck is used to helping visitors separate fact and fiction, so she immediately points the man to notable graves, providing a brief history on each.

As usual, her knowledge has the visitor -- and his two friends who have now walked over to join the party -- captivated. Steck cuts the lesson short due to another engagement. But she makes sure they know there’s more to find out.

“I give tours, too, if you’re ever interested,” she said. “Just go to the Southport Visitors Center and tell them you spoke to the woman who’s always out in the old cemetery, and they’ll give you one of my cards. They’ll know it’s me.”

STAY CONNECTED: Keep up with the area’s latest Brunswick County news by signing up for the Brunswick Today newsletter and following us on Facebook and Instagram.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Southport NC resident Musette Steck remains Moral Monday champion