‘We can steer these into hurricanes.’ How drones by air and sea help Florida’s forecasts

When it comes to forecasting the world’s most powerful storms, the more data you have, the better.

Now, new air and sea drones are helping NOAA hurricane scientists explore the storms from never-before-seen angles.

From pinpointing potentially lifesaving details about storm conditions to answering questions previously unknown to science, the new tech is filling crucial gaps in understanding.

“I have so many questions from looking at data over years,” said NOAA Hurricane Field Program deputy director Heather Holbach. Holbach has flown through hurricane eyewalls nearly 100 times in pursuit of her research to refine wind speed estimates.

The only way to answer those questions, Holbach says, is with more data from inside the storms — and drones can go where humans can’t.

“I’m super excited to see where this is going to take us,” she said.

Take, for instance, the Saildrone Explorer. It’s an “uncrewed surface vessel” — that’s a boat-like drone.

The 23 feet-long, 1,000-pound, bright orange drone is solar- and hydro-powered, and it’s remotely controlled via satellite by teams around the world.

It continuously collects info about its surroundings to provide data points including salinity, water temperature and turbulence, as well as nearly real-time visuals from the ocean’s surface.

Drones go inside hurricanes

Since NOAA began a partnership with the California-based company Saildrone in 2014, the autonomous aquatic data collector has become a major boon for hurricane scientists.

“The most valuable thing is we can steer these into hurricanes,” said NOAA oceanographer Greg Foltz. “That’s unique.”

The data that the Saildrone collects from inside the storm’s fury, where waves can reach 90 feet tall and winds climb to 125 mph, is fed directly into hurricane models.

“We hope ultimately to improve the models and improve hurricane intensity prediction,” Foltz said.

One particular concern is rapid intensification, or when hurricane winds increase by 35 mph or more in a 24-hour period. It’s a pattern that is thought to be increasing with climate change, and more accurate predictions could help forecasters warn communities sooner.

NOAA does not own the vessels. Instead, they pay Saildrone for the data they collect. Saildrone and NOAA collaborate throughout the hurricane season as they plan where to deploy the drones.

This hurricane season, there are plans to send 10 of the drones into the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. Two will remain on land for rapid deployment should a hurricane pop up in the Gulf, including one in St. Petersburg.

Applications aren’t limited to hurricanes. Saildrones and other autonomous tools could also be used to measure changes in ocean conditions over time or harmful algal blooms like red tide, researchers added.

Insights from all angles of the storm

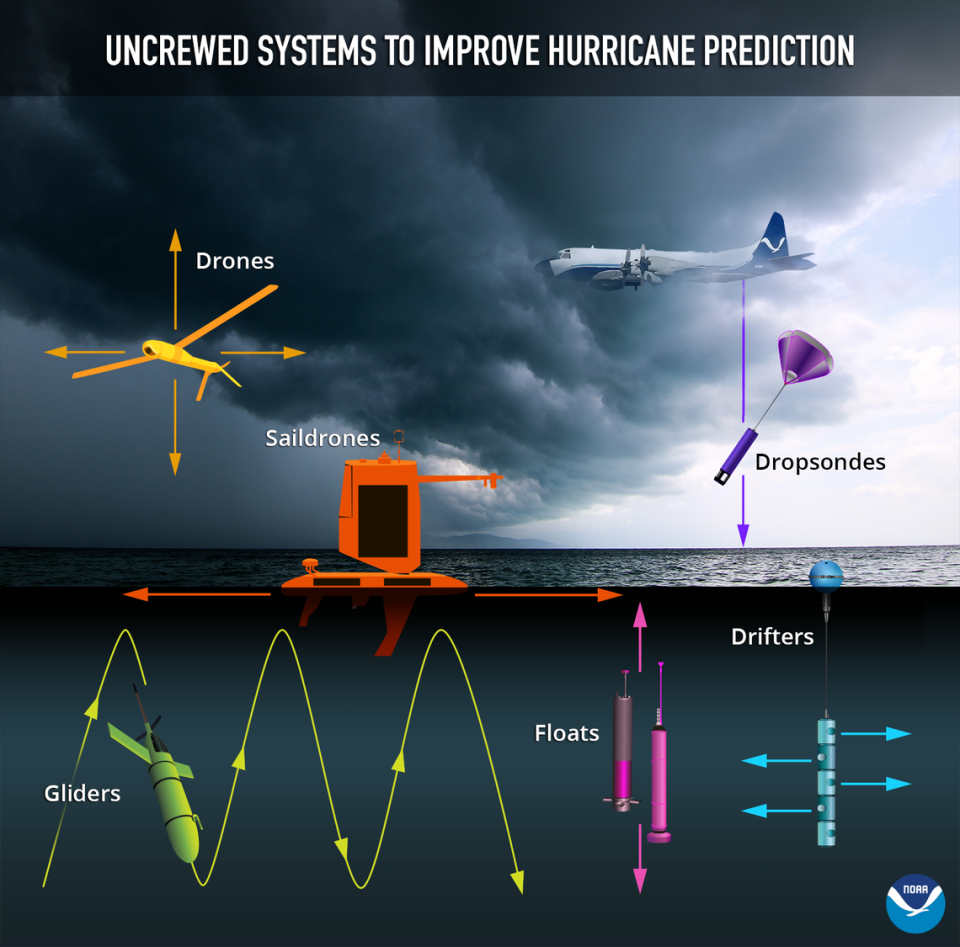

Drone tech and other remote devices are now being used to measure storms at all angles.

Here’s a look at some of the tools being deployed by NOAA:

Below the surface: Gliders, battery-powered drones that look like torpedoes, use buoyancy and gravity to glide up and down the water column. They provide water temperature, salinity and other data and can operate for months at a time.

At the surface: Saildrone Explorers cruise where the sky meets the sea — a crucial place in the development of hurricanes. They measure data points like air, water and sea surface temperature, salinity, relative humidity, barometric pressure and wind speed and direction. Last year, the Saildrone provided visuals from a different perspective — inside Category 4 Hurricane Fiona. “Being able to see those videos from the Saildrone is just eye-opening because I’m very interested in what’s happening at the ocean’s surface,” Holbach said.

In the air: “Uncrewed aircraft systems,” also known as drones, are sent into the layers of the hurricane where NOAA’s crewed planes can’t descend — heights of about 4,000 feet and below. The drones measure for maximum wind speed, pressure, humidity, turbulence and other factors. Drones in various phases of testing include the Blackswift, a small, lightweight flier, and the larger Altius, both of which penetrate into the storm.

Last year, the Altius rode into Hurricane Ian’s Category 5 force winds when the Hurricane Hunter crew had to turn back for safety. The drone lasted 102 minutes and was able to transmit back to the NOAA crew from 130 miles away.

Another new addition to the drone fleet is the Dragoon, an aircraft in the testing phase that can fly for over 26 hours and will be used to monitor the outside perimeter of storms.

Riding the wind: Dropsondes, small tube-shaped instruments outfitted with sensors, are launched directly into the storm from NOAA’s crewed aircraft. As they catch a ride on the hurricane express, they report vital info back to scientists.

This hurricane season, NOAA scientists are looking to bring all the helpful tech together in one hurricane.

“If we can get the glider, the saildrone and uncrewed aircraft all measuring in the same place at the same time, that gives scientists a really incredible picture of the air-sea interaction with dynamics,” said NOAA Corps Captain William Mowitt, who directs the agency’s Uncrewed Systems Operations Center.

Data collected by the uncrewed technology will also feed into the Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System — a new forecast model that NOAA is launching this year.

NOAA received $6.9 billion in the 2023 federal budget, with an emphasis on programs that improve the agency’s ability to “predict extreme weather associated with climate change.”

Will drones replace NOAA’s Hurricane Hunters?

Are drones taking over for humans in exploring hurricanes? Not any time soon.

With the next generation of NOAA’s famous “Hurricane Hunter” aircraft currently in development, people are still going to be flying into storms for many years to come, said Joseph Cione, lead meteorologist with NOAA’s Hurricane Research Division.

However, he predicts a “slow transition” toward fully uncrewed systems over the next several decades.

For now, NOAA researchers say going into the storm still provides valuable firsthand insights.

“That’s one of the things I love about getting on this plane and flying,” Holbach said inside of NOAA’s hurricane hunting P-3 Orion aircraft, nicknamed “Miss Piggy.”

“I learn so much just from looking out the windows, seeing what it looks like and being able to immediately connect that to the data.”