Stetson University art exhibit displays labor strife from the past and the present

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

There's a thread that runs from striking silk workers in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1913 through the picketing Hollywood writers of last summer: Fear of how technology might eliminate their livelihoods.

That strand is on display at Stetson University's Hand Art Center, where a modern-day artist has responded to a series of works by a Modernist more than 100 years ago. The result is "The Beauty of Politics: Oscar Bluemner and Luca Molnar," on display until March 23.

The artists' styles are a study in contrast, not only to each other but to the nature of most political art, says Katya Kudryavtseva, assistant professor of art history at Stetson, who curated the exhibit.

"We see political art, most people think it’s something slogan-filled. It’s something that can be immediately understood, something that can be immediately interpreted, which, you know, this is how propaganda works," Kudryavtseva said. "It has to be understood in a split second."

While striking in their own right, neither the Bluemner nor Molnar works present in the way, say, the Obama "Hope" poster, does. There are dimensions of nuance in Bluemner's depictions of the Paterson skyline, dominated by silk mills, while in Molnar's mosaics, patterns with abstract meanings are layered with images that are not nuanced but reference historical thread to unwind.

"This layered approach allows the spectator to have a dialogue about politics, about those images and so forth," Kudryavtseva said. "They do not give ready answers. They do not say, ‘This is what is right and this is what is wrong.' ... Preaching to the choir, it has its benefits, but you know, it’s often not very interesting as art. Works (of Bluemner and Molnar) can be appreciated on multiple levels.”

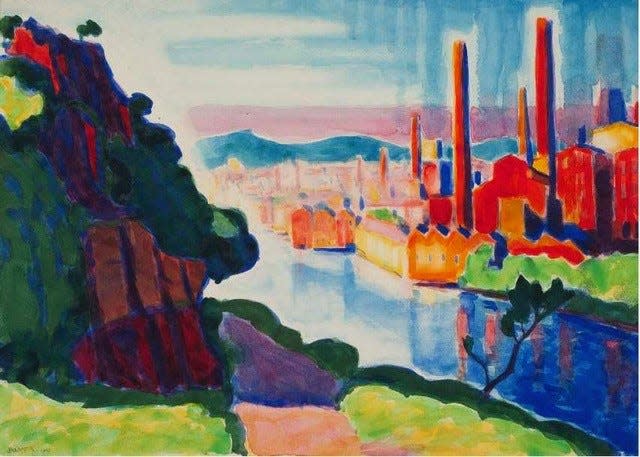

Bluemner's paintings of Paterson

Bluemner (1867-1938) was a Prussia-born Modernist painter whose background also included training as an architect. He moved to the United States in 1892 and eventually made his way into a circle of artists led by photographer Alfred Stieglitz, husband of Georgia O'Keeffe.

Bluemner was well-regarded by critics but mostly lived as a starving artist who died by suicide in 1938. One of his children, Vera Bluemner Kouba, a DeLand resident who died in 1997, bequeathed more than 1,000 of her father's paintings.

Hand Art Center Video: Luca Molnar: The Beauty of Politics

His paintings of Paterson typically depict landscapes, buildings, objects − not people.

He was living in New Jersey at the time of the silk strike, which history remembers for its size (25,000 strikers), but also its significance as a moment of change. It was a workforce of varying European ethnic groups that had, to that point, been believed by managers to be unlikely to unionize because of conflicts amongst themselves. But the Paterson workers were different.

"They successfully overcame differences of nationality, craft, and gender," wrote Steve Golin for PBS' American Experience website. "Their democratic self-organization served as a school in self-management."

The Paterson weavers and dyeists had not had a raise in some 20 years and pushed back against demands on productivity. Where silk weavers typically operated two looms, the machines used to turn thread into fabric, some mills had begun assigning workers to three and four looms at one time, driving fears that machines would soon eliminate jobs.

The strike was ultimately unsuccessful; the workers returned without having their demands met. But it resonated.

The skyline of Paterson, dominated by mills and dye houses, was a subject of Bluemner's, and prior to 1913, he bathed the geometric forms representing buildings in a yellow sunlight. But in similar renderings after the strike, he used a bold, bright red.

Bluemner's frequent use of that palatte earned him the nickname, "The Vermillionaire," in reference to the vermillion color family of red and red-orange.

Uninitiated viewers today might look at Bluemner’s choice of red on the Paterson mills as something festive, Kudryavtseva said.

"But for a contemporary artist and for Bluemner himself, it’s a particular political messaging," she said. "If you’re siding with the red flags, it’s a message of solidarity.”

While Americans might associate the red with Soviet-style communism, that didn’t come until after the 1917 Russian revolution. Still, for workers during the 1913 silk workers’ strike, red was a message of solidarity.

In her curator's notes, Kudryavtseva says Bluemner's choice of painting Paterson was a political statement. And his decision to paint the buildings and not people was also a statement. She quoted him: "The world is tired of seeing … painters rush from the poles to the equator … to compete with the photographers and the illustrated weeklies.”

Luca Molnar: Historical patterns repeat

Molnar was born in 1991 in Budapest, Hungary, but grew up in North Carolina and New Jersey, near Paterson.

Encouraged by her mother, Molnar painted, sculpted and studied art at Dartmouth and then New York University, eventually landing a job as assistant professor of studio art at Stetson.

Last year, Kudryavtseva − her colleague at Stetson − asked her to consider painting a series in response to Bluemner's "political" works around the silk strike, and it struck a chord. Molnar said she has long been interested in history and the labor movement, while also finding Bluemner's use of color inspiring.

“What interests me the most about history in general is the ways that we tend to learn about it and think about are these sort of discrete things that happened long ago, but the patterns themselves repeat seemingly endlessly," Molnar said.

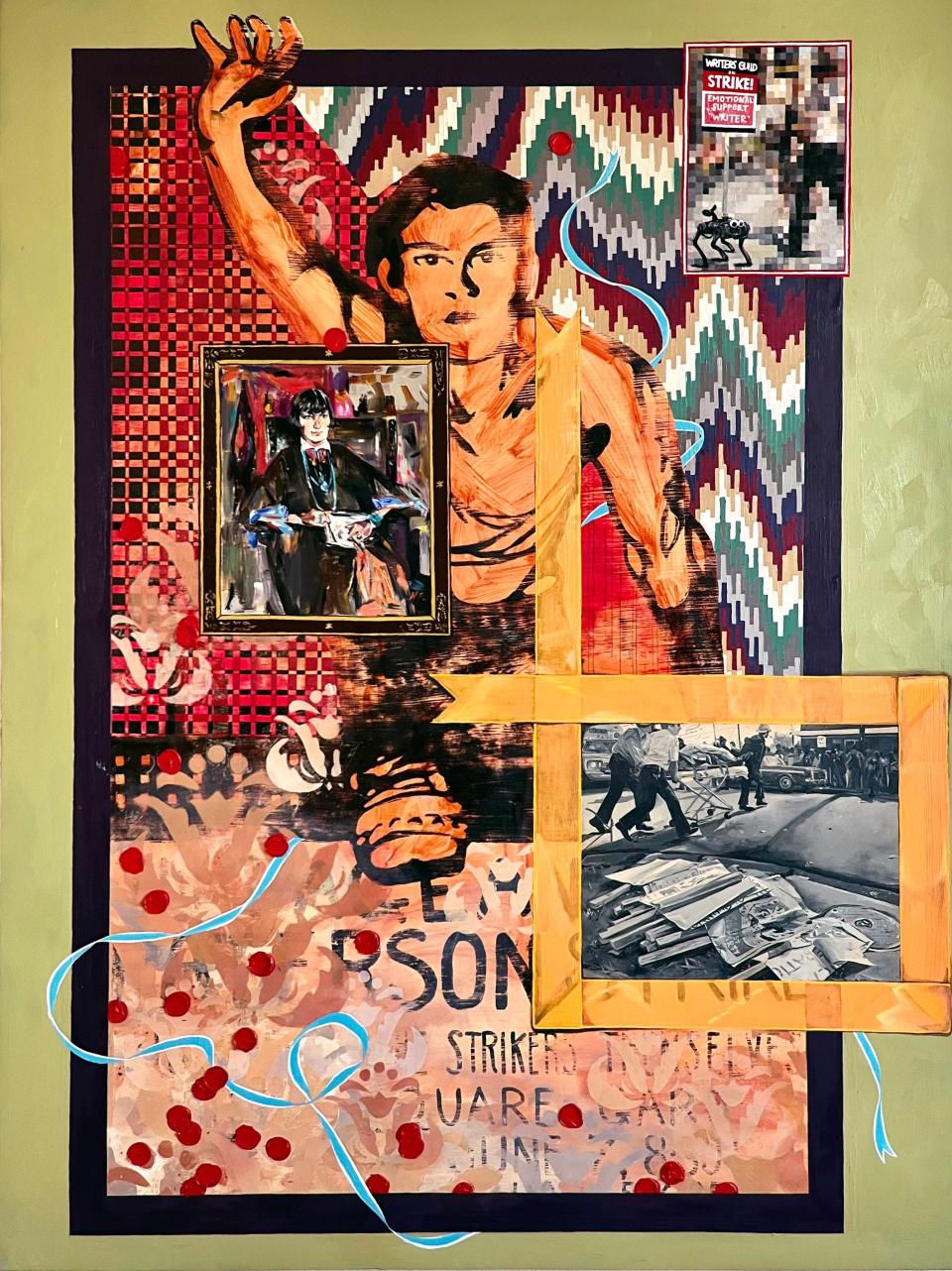

Her piece "Hot Strike Summer" specifically references the 2023 Writers Guild of America strike over, among other issues, concerns that Artificial Intelligence might be used by Hollywood film and TV producers to further cut into the work available to them. She saw commonalities with the Paterson strike.

"The workers were very scared of the effect on them in terms of cutting hours, expectations for this unachievable degree of efficiency and similarly, what a lot of industries right now are facing with AI is this fear of obsolescence, this – not necessarily fear of technology but finding ways to incorporate it that protects workers, protects intellectual property – so that to me is extremely parallel," Molnar said.

For the show, Molnar produced three larger collage-like pieces peppered with historical imagery and textures. From a distance, they resemble mixed media: Old news clippings and other imagery atop fabrics. But the works are all painted with oil and acrylic.

"Hot Strike Summer" also features an image from a poster dating to 1913. During the silk walkout, in order to draw more attention to their cause in nearby New York City, the striking workers performed in a pageant, or play, at Madison Square Garden. The poster for the event was also a centerpiece for the Stetson exhibit.

“It’s so weird, to be honest. It was a strange idea," Molnar said. "I found it compelling because it was put on while the strike was happening but very much as this sort of artistic propaganda."

Within "Hot Strike Summer" is a copy of a framed portrait of Mabel Dodge, the arts patron and writer who financially supported the strikers. Also, Molnar pays homage to the Hollywood writers' strike using an image of a robot dog holding a strike sign, which she said "speaks to the difficulty of using AI morally in a way that doesn’t upend people’s rights, writers’ roles in society.”

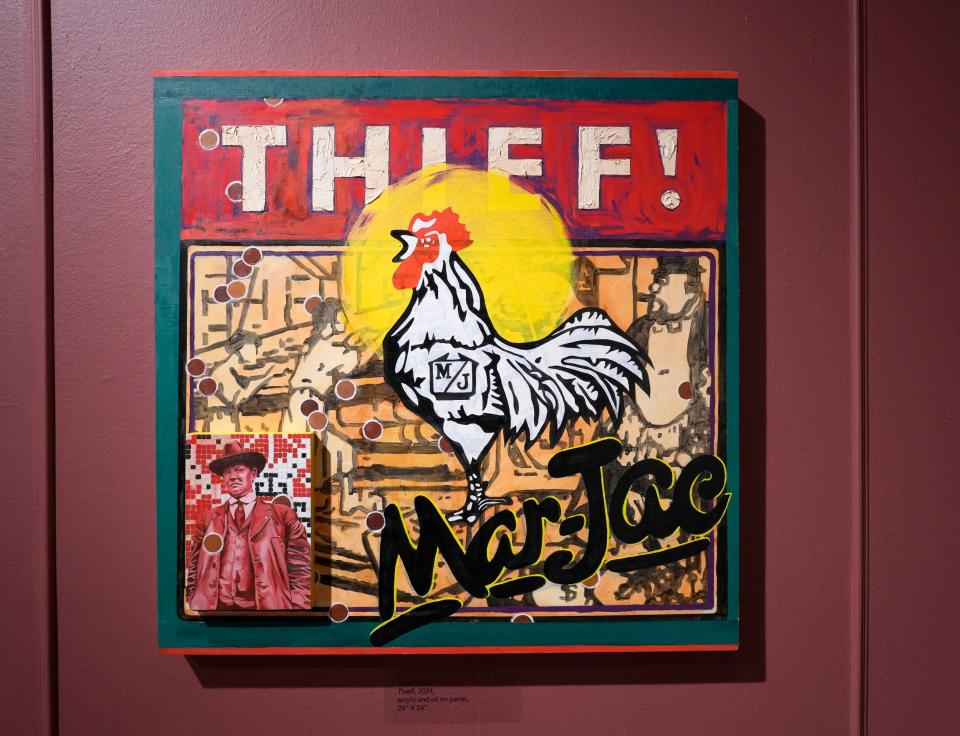

Two other works intermingle historical labor references.

One is the deadly 1979 encounter between members of the Ku Klux Klan and American Nazi Party and Communist Worker Party demonstrators in Greensboro, North Carolina.

The event was billed as a "Death to the Klan March," but ended with five of the marchers being killed by gunfire from the Klan and local police, who were later found by the city to have failed to warn marchers of the violence to come. The Communist Worker Party members were largely from outside the South and had been in Greensboro in an attempt to unionize textile workers.

Another touches on a 1931 Tampa tobacco workers' strike, which, in part, sought to retain Lectors, pre-radio entertainers who read novels and newspapers while the workers labored.

Yet another references a fatal industrial accident last July, where 16-year-old Duvan Perez, a native of Guatemala who was working at a Mar-Jac Poultry plant in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, under a false identity. He was killed while cleaning a machine that had not been properly disconnected from its power source.

The challenge of tying those events together visually played into a strength of Molnar's. She has been using textures in much of her work.

“This style of painting has built up over time quite a bit. Starting in grad school, I got really interested in painting patterns, but at that point, I was making much more abstract paintings," Molnar said.

Initially, she often used maps to make historical and political connections. However, she found using textures inspired by common items such as fabrics and upholstery more directly spoke to the narratives she was attempting to reveal.

"So figures kind of started, slowly, making their way into the paintings. And then I kind of let go of the map and I started thinking more about this literal layering of the images, one on top of the other," Molnar said. "All of that is honestly relatively new.”

Happy Birthday: Stetson celebrates artist Oscar Bluemner's 150th

Perego's big night: Daytona artist receives presidential honor for volunteer service

This article originally appeared on The Daytona Beach News-Journal: Stetson artist responds to Oscar Bluemner's Paterson silk strike works