Still 'Amazin' ': New York Mets fans haven't forgotten Jack DiLauro, even 53 years later

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

MALVERN – Jack DiLauro wanted to become a Major League Baseball pitcher.

He did.

His admittedly oversized ego had also primed him to become one of the best lefty hurlers to ever play the game; a Cy Young-award winner in the making; and ultimately a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

He's none of the above.

"I think it's still bittersweet for him," explained his wife, Jane DiLauro.

Like most pro ballplayers, Jack DiLauro's career didn't go as planned. By the time it ended in 1972, he'd toiled in the minor leagues for all or parts of 10 seasons. His win-loss record in two campaigns in the majors was 2-7, though he primarily appeared as a reliever in his 65 games of action.

More: NY Mets 1969 world champions: Most memorable moments

More: Why no team will ever be able to replicate what the 1969 Mets did

Not the kind of stats that would typically place someone high on the list of even the most dedicated autograph-seekers. But at age 78, a half-century removed from the game, DiLauro still receives between 200 and 300 requests for his signature per year. The onslaught of balls, postcards, trading cards and other memorabilia arrive on an almost daily basis in the mail at his Lake Mohawk home.

A handwritten letter last week began with: "Hello Mr. DiLauro, my name is Brady. I'm 15 and I like to collect autographs from great players like you ..." A typed letter from a man in Campbell, California, also from last week, opened with: "Dear Mr. DiLauro, Happy belated New Year to you!"

DiLauro reads every one.

He signs and returns everything.

You see, with apologies to the late Andy Warhol (if he ever really did say everyone would experience 15 minutes of fame), the true measure of a person's fame lies in the eyes of the beholder.

'Just a lovable team with no real stars, just a bunch of platoon players.'

For starters, just making it to the big leagues is a rare feat. The grand sum of men who've appeared in a Major League game since the creation of the National League in 1876 is 19,969, according to the Baseball Almanac.

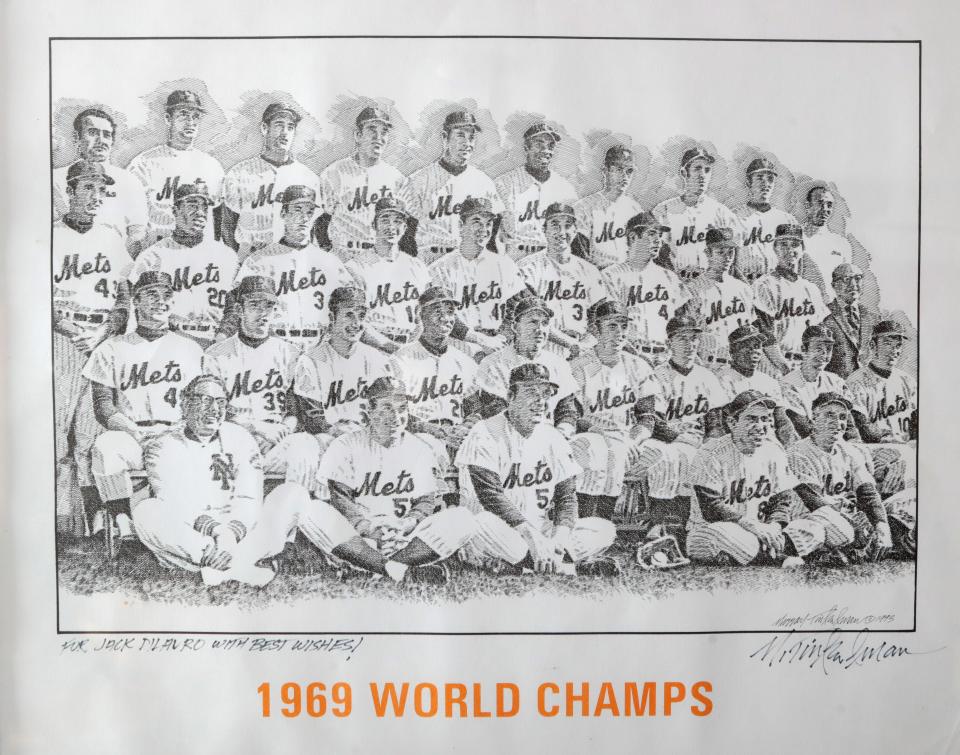

Then consider the magical 1969 season when DiLauro pitched for the New York Mets, a season where everything went right for him and the team. That's when DiLauro earned his everlasting fame.

That team, dubbed the Amazin' Mets and Miracle Mets, ranks up there with some of the sport's most universally beloved and best squads, such as the 1927 "Murderer's Row" Yankees, 1950 "Whiz Kids" Phillies and 1979 "We Are Family" Pirates. Not just because the Mets won 100 regular season games, disposed of the Braves in three straight then cruised to a World Series title over Baltimore in five games.

The 1969 Mets were a feel-good story.

"Just a lovable team with no real stars, just a bunch of platoon players," said Gary Kaschak, who along with DiLauro teammate Cleon Jones co-authored the book "Coming Home: My Amazin' Life with the New York Mets." The hardback version will be released this summer.

The franchise was only in its eighth season. The team was a habitual underdog. The often bumbling Mets regularly lost 100 games a season. They'd finished no better than ninth place in the National League, before the league split into East and West divisions for the 1969 campaign.

What they had, though, was lots of young talent.

Future Hall of Fame pitchers such as Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan. A soon-to-be great relief pitcher named Tug McGraw, who'd later be immortalized in the song "Live Like You Were Dying," by his country music superstar son, Tim. A superb mix of solid young stars, role players and journeymen, including Jones, Bud Harrelson, Tommie Agee and Donn Clendenon. And an old school manager, Gil Hodges, who seemed to put everyone in the right place at the right time.

"He was a very quiet man, but when he spoke, you listened," DiLauro recalled.

Kaschak said the team captured the heart of New York for so many reasons. Not too long before the Dodgers and Giants had exited the city for the West Coast. The Yankee dynasty had ended with Mickey Mantle's retirement after the 1968 season. America was in the midst of the Vietnam War. Martin Luther King had been assassinated. Woodstock was underway.

"The Mets were a welcome distraction from all that; it wasn't just in New York; it was everywhere," Kaschak said.

'My mental state was bad ... depressed.'

During the winter prior to that season, DiLauro figured his career may be coming to a close.

At 25 years old, the 6-foot-2, 185-pound Akron North High product who went to the University of Akron to play football, had been in the Detroit Tigers minor league system since 1962.

He'd spent offseasons working factory jobs to make ends meet, then working out alone by throwing baseballs against a wrestling room mat in the old Memorial Hall at Akron, or tossing pitches to the father of his first wife.

"I'm not complaining; it's all I had and knew," DiLauro said.

By then, he'd compiled a 65-48 record as a career minor leaguer. He was 11-6 in 1968 at Detroit's AAA team in Toledo. But he was increasingly frustrated he never got the call to the big leagues.

"My mental state was bad ... depressed," DiLauro said. "I was 8-0 at one point and still didn't get called up."

Then, he learned he'd been traded to the Mets.

"Just great," he told himself with mounds of sarcasm.

He'd never sniffed the majors with the Tigers. Now, he was headed to the Mets, who were full of young, live arms. Besides Seaver, Ryan and McGraw, the organization was loaded with other upcoming star pitchers, such as Jon Matlack, Jerry Koosman and Gary Gentry.

DiLauro couldn't have picked a worse destination.

'I might have had the best pickoff move in the minors or the majors at the time.'

He went to spring training with the Mets before the 1969 season, then was assigned to the team's AAA farm club in Tidewater.

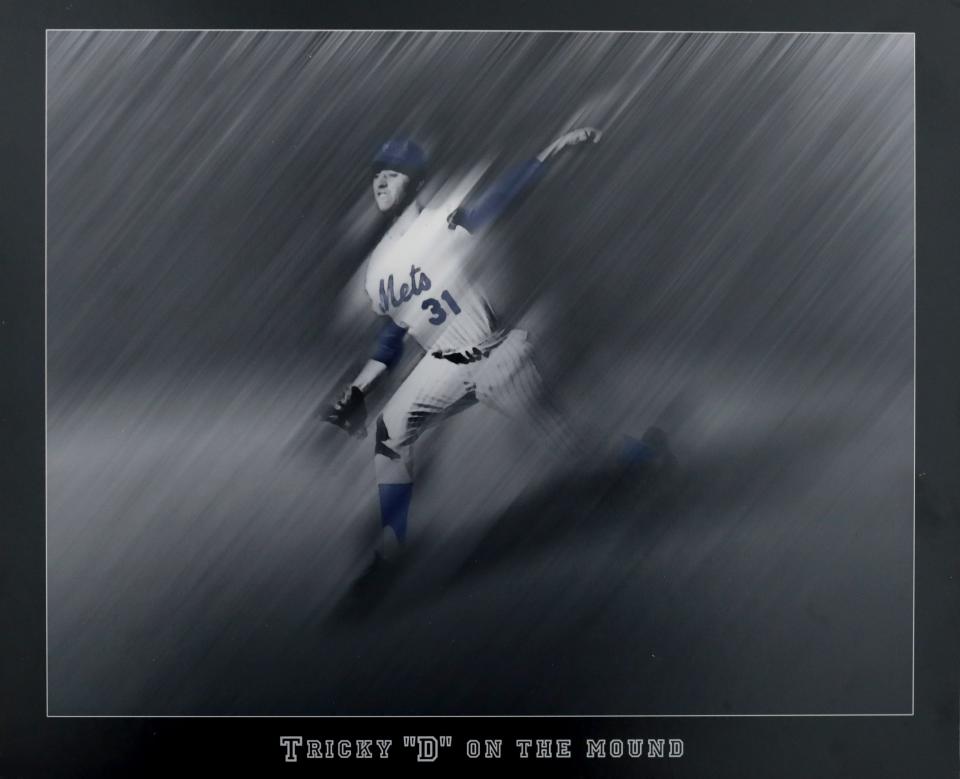

DiLauro, who owned an average fastball at best, had always relied upon his curveball, changing locations and speeds to keep batters off balance. He later learned that Whitey Herzog, a future Hall of Fame manager who was then the Mets' farm director, was a fan of DiLauro's ability against lefty hitters.

"He knew I could get them out and I might have had the best pickoff move in the minors or the majors at the time," DiLauro said, explaining how he'd patterned it off his idol, the great Whitey Ford.

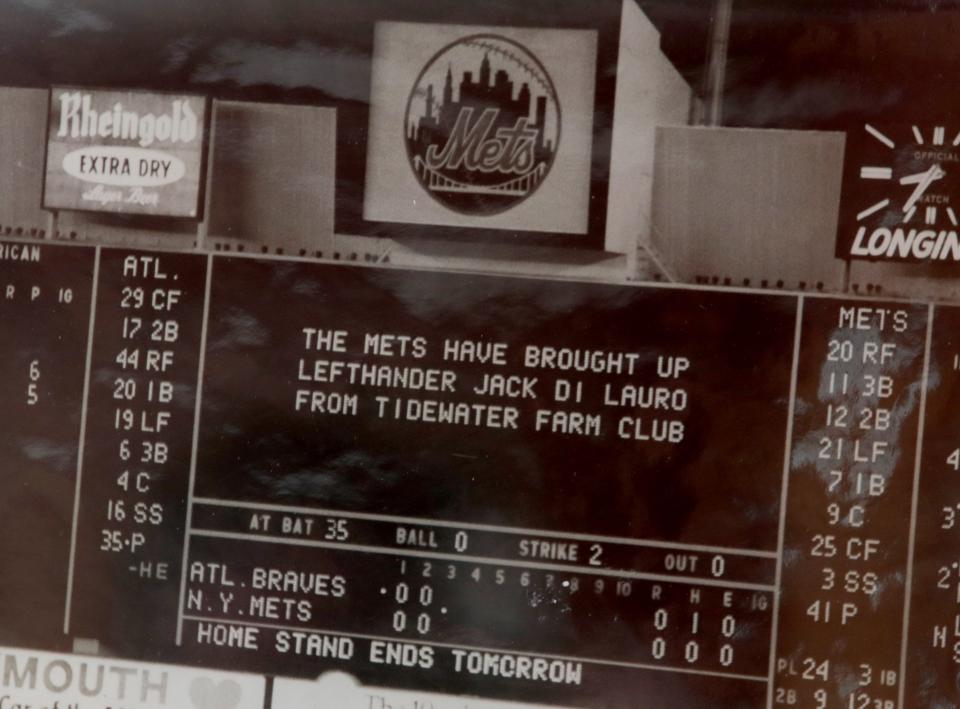

DiLauro impressed in 1969 at Tidewater. A month into the season, he was 2-1 in four starts, with an admirable earned run average of 2.67. On May 11, future strikeout king Nolan Ryan went on the disabled list.

The Mets summoned DiLauro to fill in.

On May 15, at Shea Stadium, he pitched two innings of scoreless relief in a loss to the Braves. Over the next two weeks, he shined in two more similar outings. Then came the game, which likely cemented DiLauro's place on the roster for the rest of the year — despite Ryan's return.

On June 4, again at Shea, DiLauro started against the Dodgers. He allowed only two hits in nine innings and exited with the teams knotted in a 0-0 duel. The Mets went on to win 1-0 in 15 innings. It was their seventh straight victory in what would become an 11-game winning streak.

'If I'd have pitched, that would have meant we were in trouble; and we never really were.'

By season's end, DiLauro's record was a deceiving 1-4, because he'd logged a stellar earned run average of 2.40 in 63 innings. It was the second lowest ERA among the Mets relief corps, and was a full run lower than Ryan's.

Through that summer, he'd held his own. He faced star hitters like Lou Brock, Joe Torre, Willie Stargell, Roberto Clemente, Hank Aaron, Tony Perez, Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, Bobby Bonds, Willie McCovey, Ron Santo, Billy Williams and Ernie Banks. Sometimes, he got them out; other times they won the battles.

DiLauro didn't appear in the playoff games vs. Atlanta, nor the World Series vs. the Orioles. Not because he was in the doghouse. The Mets starters mostly dominated, so he wasn't needed in relief.

"If I'd have pitched, that would have meant we were in trouble; and we never really were," he explained.

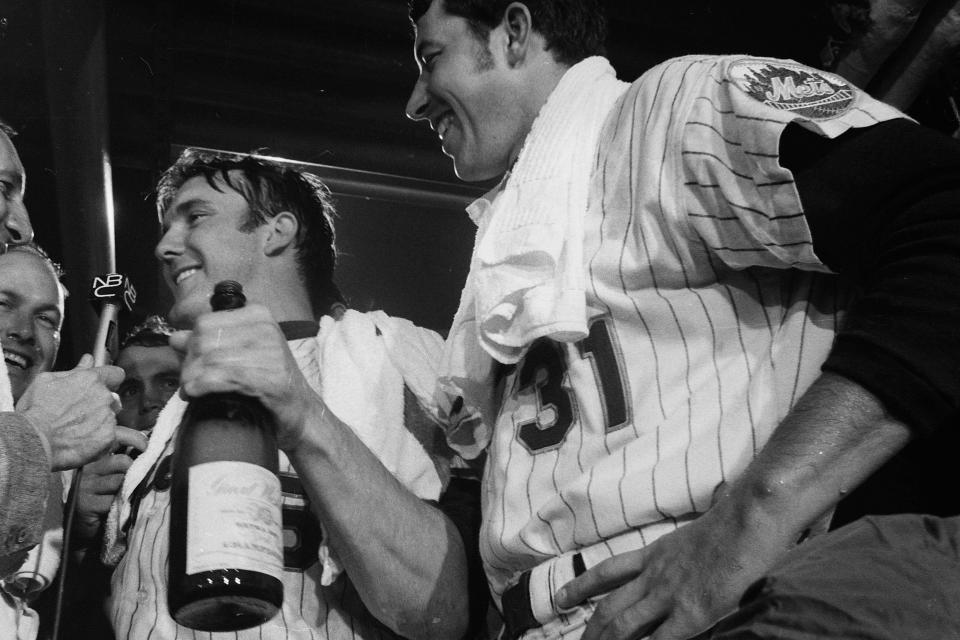

DiLauro was in the bullpen when Jones, the Mets' leftfielder caught a fly ball off the bat of Dave Johnson to end Game 5 of the World Series. Jones famously went down on one knee to celebrate the title.

Shea Stadium erupted. Fans stormed the field. DiLauro and the pitchers headed to the clubhouse. That fall, he and other players made personal appearances throughout the New York area.

The Mets loved New York and New York loved the Mets.

That winter, though, DiLauro learned the team wasn't keeping him on the roster for the next season. Instead, they'd invite him to spring training where he'd get an opportunity to earn a spot.

DiLauro understood — the game was a business.

After the 1972 season, he was done at age 29.

He wound up signing with the Houston Astros for the 1970 season. It was the biggest payday contract he ever landed, $16,000. It was still less than one of his brothers earned making tires at Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. in Akron.

DiLauro appeared in 42 games, compiling a 1-3 record with a less than stellar ERA of 4.28. The next two years he played for minor league teams in the Padres, Braves and Montreal organizations.

After the 1972 season, he was done at age 29.

He continued a career in the sporting goods business, which he'd began while playing ball. He played some more amateur ball locally. He helped coach young players. At one point, he sold his World Series ring at auction — it's something he refuses to talk about now.

Doug Gladstone, who authored the book "A Bitter Cup of Coffee: How MLB and the Players Association Threw 874 Retirees a Curve," said a DiLauro teammate told him the ring was sold for financial reasons.

DiLauro was one of the former players caught in a purgatory of sorts when MLB pension rules changed in 1980. Gladstone detailed how the new setup required four years of big league service for those who played between 1947 and 1979 to be eligible to receive a pension.

Instead, DiLauro and those like him are paid an annual amount based on games of service, with a ceiling of $10,000, which can't be passed on to his wife after he dies. Gladstone pointed out that's a far cry from the vested players who followed, who can earn as much as $245,000.

'That's where Tom Seaver used to sign.'

DiLauro said the whole pension issue was and continues to be a confusing mess, but he tries to keep tabs through an alumni association.

He's even closer to the living Mets from that 1969 team. He knows details about where many of them live and their current health. They get to exchange stories when they go back to New York for reunions and get treated like royalty — especially during the 50-year anniversary in 2019.

DiLauro got a key to the city from then-Mayor Bill de Blasio. DiLauro keeps it in his family room, on a counter above a drawer full of a dozen blue Sharpies that have arrived along with autograph requests over the years. A few pieces of memorabilia, primarily related to the 1969 Mets, have special places on the walls.

One recent day, DiLauro pulled out a ball that had arrived in the mail. It had already been signed by teammates Al Weis and Koosman. The latter's signature was in the "sweet spot" of the ball, where the seams come closest to converging — the desired location is reserved for stars on a team ball.

"That's where Tom Seaver used to sign," DiLauro said.

Koosman inherited the honor.

DiLauro signed on the other side of the ball.

This article originally appeared on The Repository: 1969 Amazin' Mets: Malvern's Jack DiLauro still signing autographs