'And Still We Rise': Exhibit at Galveston's new Juneteenth museum tells powerful history

GALVESTON — Let's dispense with one Juneteenth legend right away.

Major Gen. Gordon Granger, commander of the District of Texas, did not read, as is often imagined, General Orders No. 3 — which informed Texans that slavery had ended — aloud from a balcony of Ashton Villa, the 1859 brick Victorian Italianate mansion on Galveston's Broadway Avenue.

Instead, on June 19, 1865, the ordinance issued by the general was more likely posted at key points around the port city.

In fact, the Galveston Historical Foundation and the Texas Historical Commission chose the Osterman Building, not Ashton Villa, for the official Juneteenth state historical plaque because that's where Granger's Union headquarters had been located, and thus the point of origin for the ordinance.

More:'We didn't let this place die': St. John Colony, Texas, endures for 150 years of grace

The Ashton Villa legend is easy to track down, according to Kathleen DiNatale, an expert guide to a savvy new Juneteenth museum, located in the mansion's former carriage house.

"For years, people gathered to celebrate Juneteenth on the Ashton Villa grounds," she says. "And for years, (state) Rep. Al Edwards read the ordinance to the crowds. I'm not absolutely sure it was from a balcony, but he did read it on the grounds."

At other times, the ordinance might be read by a historical reenactor.

During the 1970s, Edwards, a Democrat from Houston — sometimes called the father of Juneteenth — pushed a bill to name June 19 a state holiday. The legislature passed the act in 1979, and Gov. William P. Clements Jr. signed it into law. The first state-backed Juneteenth holiday came in 1980.

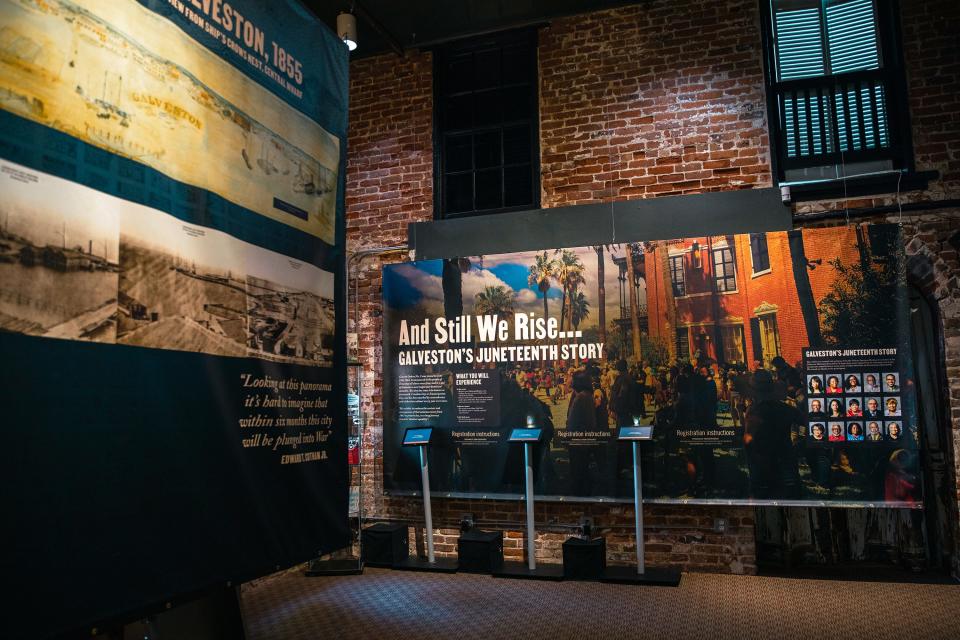

These days, a monumental statue called "The Legislator," often identified as Edwards, stands guard by the garden path to the Ashton Villa carriage house, which now serves as home for "And Still We Rise: Galveston's Juneteenth Story," a permanent exhibit that opened on June, 19 2022. The previous year, President Joe Biden signed a bill that designated Juneteenth as a federal holiday.

"This exhibit is so powerful," DiNatale says of "And Still We Rise." "People are willing to take time with it. This is history that was hidden, so when people find out about it, they are profoundly affected."

More to learn in three packed rooms

The exhibit, "And Still We Rise," is not large, only three darkened rooms arranged in an L-shape. And, at first, it's not easy to find. The parking lot lies on the north side of the villa, across from the Rosenberg Library, while the main entrance to the museum opens to the south side near a formal garden and behind an iron gate.

Nevertheless, the exhibit is packed with enlightening historical material displayed on banners, floor maps, digital touch-screen timelines, sharp photographic images, moving videos and well-chosen quotes. It's as if the museum's designers decided to use every inch of the three small spaces, all the way up to their high ceilings.

More:St. John Colony, Texas, celebrates 150 years of Juneteenth jubilees

In terms of storytelling and digital acuity, it's as up-to-date and slick as the much larger "Becoming Texas" at Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, but without the Austin's exhibit's array of key artifacts.

Among the things I noted:

Evidence from the U.S. Census that the number of enslaved people in Texas tripled in number from 1850 to 1860. Which means the practice was not receding at the time, as some have claimed.

A copy of the bill of sale for "Alek," the enslaved mason whose skills, honed in Europe, are preserved in the brick walls of the villa.

An image of Estabanico — alternately Estevanico — the enslaved African known to have explored the Southwest as part of multiple Spanish expeditions in the 1520s and '30s.

An amazing birds-eye-view map of 1871 Galveston reproduced on an amazingly resilient floor mat. I wanted to take it home with me.

Words and images from the historical foundation's African American Heritage Committee, a board that guided the creation of the exhibit.

Images and stories about prominent past Black Galvestonians. (For more on this subject, consult "African Americans of Galveston" by Tommie D. Boudreaux and Alice M. Gatson.)

An 1855 watercolor of the seaport, which shows the source of Galveston's wealth and power.

Five 1861 photos of downtown taken from the Hendley Building, which lends the scene a sharper precision than earlier paintings.

A display on the Battle of Galveston in 1863 and the Confederate recovery of the port in 1863.

An image of the Galveston slave auction house at 2200 Strand. Houston is the only other Texas city where I've been able to confirm the existence of such an auction house, more common in the Deep South.

History of Reedy Chapel African Methodist Church, which was commissioned by enslavers in 1848 to become the first African American Episcopal Church in Texas. A graceful newer building, completed in 1888, still stands.

Recorded memories of Watch Nights, when vigils and prayers of remembrance and thanksgiving were held at Black churches and go back as far back as the 1860s. Later, they were combined at some churches with Juneteenth celebrations.

More displays on the two main phases of Reconstruction, the Freedman's Bureau, Black Codes, which attempted to restrict the movement of African Americans, Jim Crow laws, which enforced segregation, and personal accounts of enslaved people, some written down in dialect during the 1930s.

Local evidence that celebrating Juneteenth slackened during the 20th century, even as the commemoration spread across the country to wherever Black Texans had migrated. The festivities picked up speed again during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and '60s.

Tackling another Juneteenth legend

In the museum's second room, the words of the Juneteenth ordinance can be seen in two versions.

"The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free," it reads. "This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere."

More:Where to celebrate Juneteenth in Central Texas

DiNatale points out that the words “absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property" were not authored by Gen. Granger, or for that matter, by Gen. Philip Sheridan, commander of the Military District of the Southwest, who had used other phrases from the ordinance in earlier orders.

That emphasis on "absolute equality," which goes beyond the language of President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, can be attributed to the chief author of the ordinance, Major Frederick Emery, an abolitionist.

Although the first two sentences of the ordinance contain some inspiring sentiments worth celebrating more than 150 years later, more than half the verbiage reflects the anxieties of an occupying military force in the face of profound social chaos.

The phrase, "the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor," combined with the "freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages" does not in any way support the earlier broad statement of "absolute equality."

The final sentence is even more ominous: "They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere."

The stories told in the museum's sections devoted to the 20th and 21st centuries remind the viewer that "absolute equality" would require more than fine words written in an ordinance.

DiNatale reports that visitors arrive at the museum from all over the country, some merely curious, others well-informed about the Juneteenth tradition.

"I have wonderful conversations with people." she says. "This place makes a difference."

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@gannett.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital Think, Texas newsletter at statestman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletters page of your local USA Today Network newspaper.

'And Still We Rise: Galveston's Juneteenth Story

Where: Ashton Villa, 2328 Broadway Avenue, Galveston

When: 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, noon-5 p.m. Sunday

Cost: Up to $10 (last ticket sales at 4 p.m.)

Information: galvestonhistory.org

Correction: Estabanico — alternately Estevanico — explored the Southwest during multiple Spanish expeditions in the 1520s and '30s, but made it to Texas only in the first one.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Galveston has a small, but powerful museum on Juneteenth