'Do not report.' 'Do NOT publish.' Why we're publishing 'The Stocking Mask' in 2022.

STAUNTON, VIRGINIA — An unmarked SUV driven by a man in uniform pulled into the Food Lion parking lot at a quarter till five on a Friday afternoon.

The cop scanned the lot for a blue Toyota family van. He drove up to it, window down, and waved a plain manila envelope containing a few dozen sheets of paper at the person standing by the back bumper.

“I normally have an official letter with stuff like this,” he said. He looked at it, shrugged, extended his arm.

I took it.

“Still looking for the rest,” he said, and drove off.

It was September 2021. After two years of searching for any official records of the 1979 Staunton "Stocking Mask Rapist" cases, I finally had a handful of police incident reports. Three of the five rapes he committed. Several break-ins where he ransacked women's dressers. All told, not even half of the crimes to which he eventually confessed.

On the top of each of the decades-old incident reports that Staunton Police Department’s Sgt. Butch Shifflett found for The News Leader, a hand-written direction was scrawled, the urgency of which still strikes a chord across the years.

“Do not release” was written on one; on another, “Do NOT publish!” The author of the directive was none other than the former chief of police, who signed off on the incident reports over 40 years ago.

At that moment in a parking lot, there was still more missing than there was found, more questions than answers.

*

It was raining outside the warehouse in Verona, Virginia, and my fingers were numb from the cold wind blowing in the open loading dock. I was realizing I had gotten in over my head.

Literally. I was precariously balanced between 6-foot-high piles of dusty, massive green hardcover books that looked like a giant’s forgotten library. Hundreds of volumes, each representing a month of the collected daily editions of The Leader newspaper.

And stacked in no particular order, of course.

Eventually I found what I was looking for — the 18 volumes representing the year 1979 and the first six months of 1980. I was going to turn every page of those giant books and see the actual articles written about the intruder who’d terrorized this small southern city for nearly a year.

What I found amazed me.

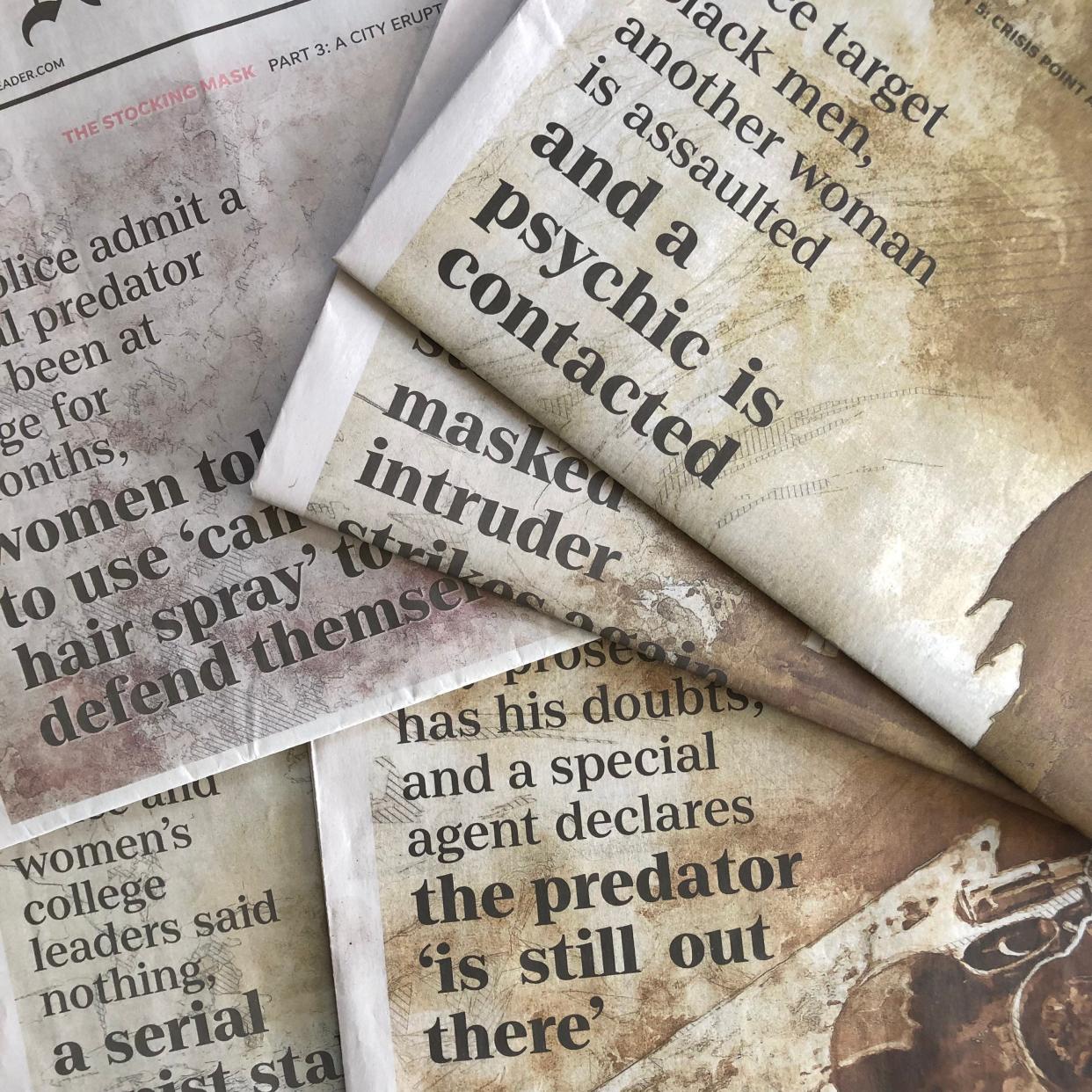

What I didn’t find intrigued me more — and angered me. No stories in The Leader warning women about multiple incidents by mid-March involving an intruder in a stocking mask, armed with a knife, attacking girls and women in our city. The 'stocking mask rapist' wouldn't make the front page of the paper until he'd raped at least three local women and attacked several more.

Read parts 1 and 2 of The Stocking Mask:

Serial rapist stalks vulnerable city while Staunton police, women’s college stay silent

After a friend attacked, a young writer and his cigar-smoking landlady wonder what can be done

*

This is my adopted home. It’s where I have raised my children from toddlers to teenagers for the last 12 years; and where my wife and I brought them to play in its wonderful parks on weekends before we moved here.

I realized a part of me, as a white male who grew up in a town in Rhode Island considered to be a very safe place for families, was seeing the Staunton I wanted to see. Looking back to 1979, I saw something different.

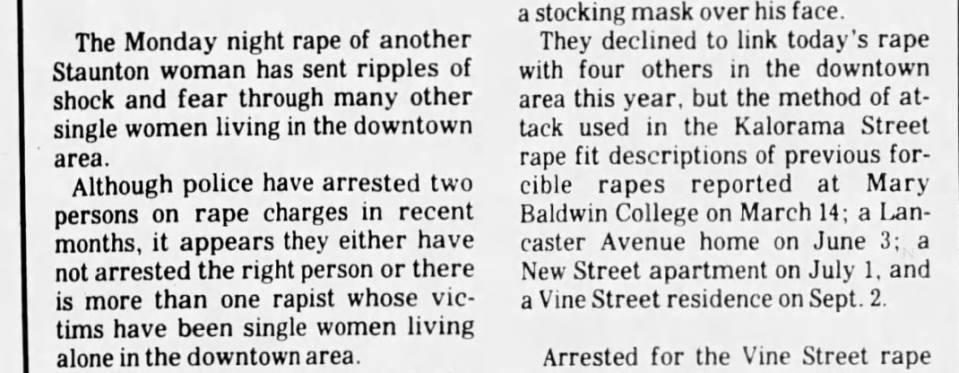

I saw a police force that botched an investigation by assigning a predator’s crimes out to multiple detectives and patrol officers as unrelated incidents, and agreed to withhold incident reports from the press for months in some cases. To protect the victims? To protect the city’s reputation? What about the women who were leaving their windows open at night, unaware a threat was roaming their streets at will in the evenings?

And when the pressure came to take action, they responded by arresting multiple Black men. At one point, two Black men were incarcerated while the man in the stocking mask struck yet again.

I saw the police and the city — and my newspaper — respond to the threat to women by publishing “commonsense” tips for how women could avoid becoming a victim. These tips included, of course, how women dress and walk and behave in public.

I realized how hard it would be as a white man to write authentically about the degree of threat felt by both white women and Black men in 1979, when I was 14.

As one Black Staunton resident told me about that year, it wasn’t any different than any other year. The crime spree, he said, “just exposed things for how they were.”

The story had to be told.

*

The only reason I was here was because I got a retired Special Agent of the Virginia State Police angry.

“Here” was the headquarters of the Virginia State Police near Richmond. More specifically, a conference room with a long table.

On the table, a 42-year-old report by the special agent who’d begun assisting Staunton police in mid-October of 1979.

The special agent had provided me the case number for his report. When the Virginia State Police rejected my second request for the report with a response saying that the exact case number was “not specific enough,” he went the extra mile and sent them his personal copy of the report.

I remember holding that report, typed on onion skin paper to aid in making carbon copies, some pages of handwritten notes on the back sides of incident reports, some on green-tinted lined paper torn from a spiral notebook. Because the report had not been copied and redacted, I was not allowed to take photos or even notes. I wasn’t even allowed to read it, just to look at it and direct a FOIA officer which documents I wanted copied.

I wanted them all.

As I had pursued records of the case, it felt like this was a story one town not only wanted no memory of but also wanted no records that it had ever happened.

Pieces of that 200-page report, including analyses of fingerprints and lie detector tests and lab results of blood tests, finally began to tell the story, at least from the investigative side, of the hunt for a predator.

But it would take more than that to catch him.

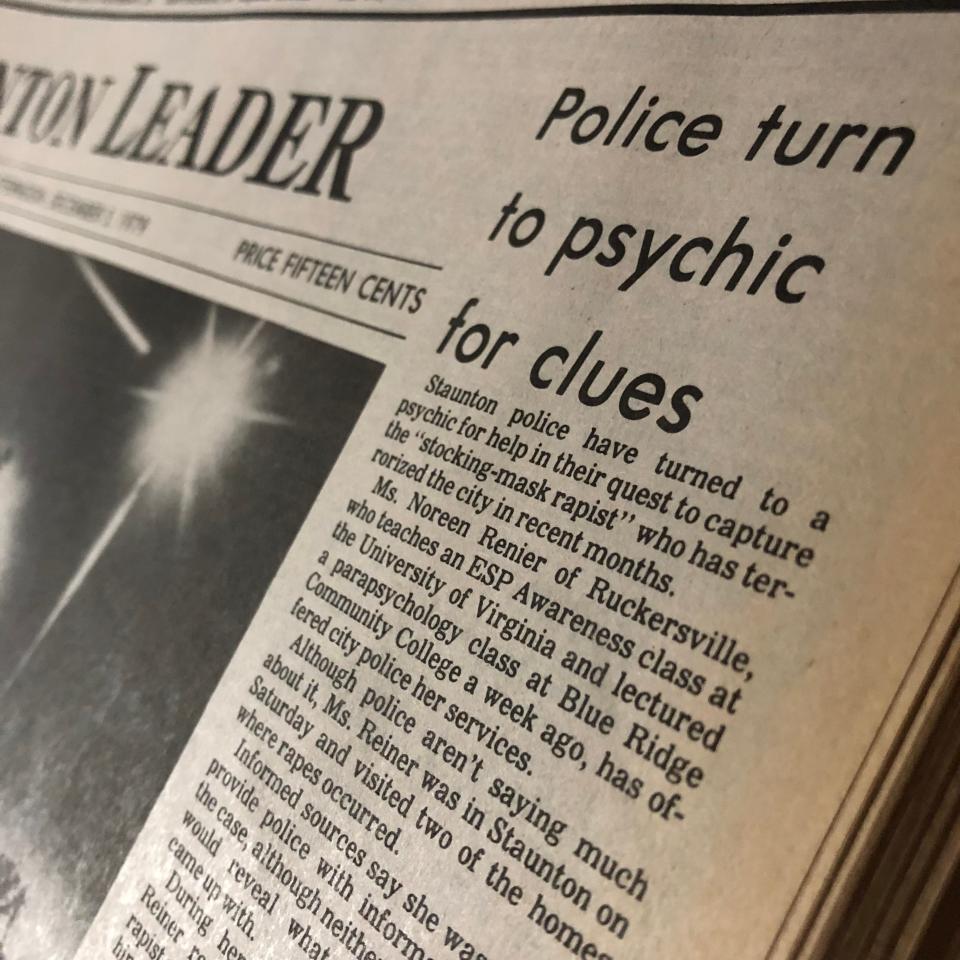

In true 1979 style, it would take a psychic as well. And that psychic would provide, in her own way, directions to the predator’s doorstep.

Every city, town, community has a story that it doesn’t want told. In this case, the city’s institutions, including my own paper, started burying the story before people could even be warned there was a predator in their midst.

Access all the parts of the story here: Catch ‘The Stocking Mask’: Follow the almost-forgotten 1979 hunt for a Virginia serial rapist

*

The modern-day News Leader reached out to people directly involved in the case, including former police officers, the commonwealth’s attorney, the public defender, journalists and editors, natives and residents of Staunton from 1979. Many did not respond but some did, and their voices are included in this story.

Some responded but chose not to be interviewed.

This is not a “definitive” history of the case. It’s likely there are a hundred people in town who could make it even more definitive if they decided to speak about their experiences of that year. It's also likely that not all their stories would fit seamlessly together. A story this old happens in a space where memory and written records don’t always agree on the details.

When those differing stories emerged in my reporting, I went back to sources to ask them which version of events they thought might be more accurate. Mostly, I stuck with the contemporaneous recording of the events, in police reports or newspaper stories.

Through its 2022 lens, this history chose to deeply focus not on the depravity and prurient nature of the crimes. This history does not try to plumb the depths of a serial predator’s mind. It does try to sketch a portrait, instead, of a city in crisis — at a time when all the institutions built to educate, inform and protect its citizens failed miserably in their missions.

— Jeff Schwaner is a journalist at The News Leader in Staunton and a storytelling and watchdog coach in USA TODAY Network. Contact him at jschwaner@newsleader.com.

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: True crime series explores untold story of Stocking Mask Rapist