Stomach-churning, creepy and surreal: David Cronenberg’s return to body horror

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

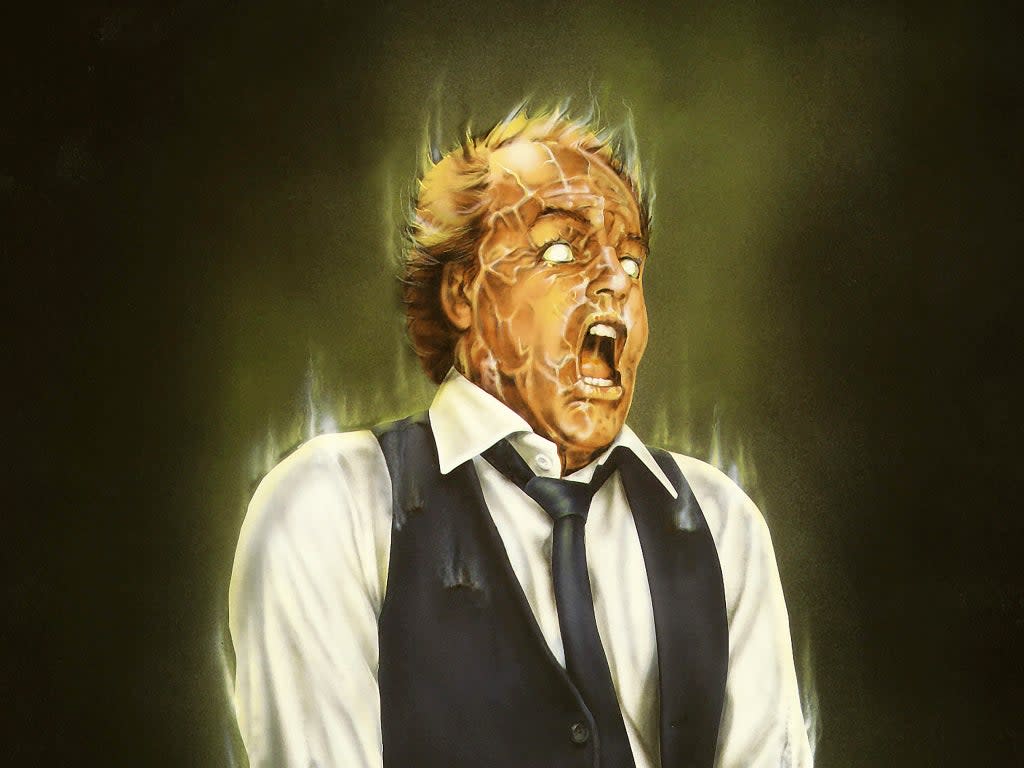

It’s the most famous scene in Scanners (1981). A bespectacled, white-collar business executive (Louis Del Grande) sitting at the front of a lecture hall, grimaces and writhes. His fingers fidget in an ever more manic fashion. The audience looks on in grim fascination. Finally, his head explodes in a huge, orgasmic eruption of blood and gore.

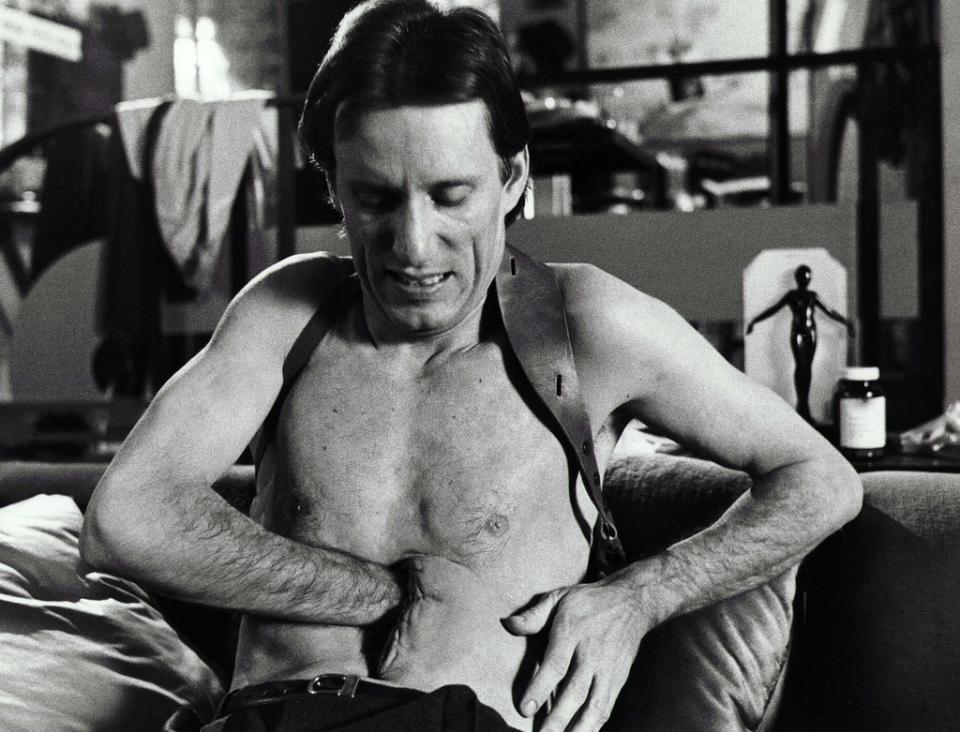

In Videodrome (1983), a VHS tape begins to pullulate and throb. Max (James Woods) is asked to “open up” before the cassette is inserted into a horizontal slit in his stomach. When Max sticks his hand into his own entrails, the cassette has mysteriously changed into a gun. A voice in his head tells him: “Kill your partners.”

Then there’s Rabid (1977). Following a road accident, Rose (Marilyn Chambers) has radical plastic surgery, which results in a blood-sucking, phallic stinger sprouting from her armpit.

These are typical scenes of “body horror” from David Cronenberg’s early films. You can find similar moments in many other Cronenberg films from Dead Ringers (1988), starring Jeremy Irons as twin doctors using sinister gynaecological instruments on mutant women; William Burroughs adaptation Naked Lunch (1991), in which a typewriter takes on a life of its own, turning into a squirming crab-like creature; The Fly (1986), with Jeff Goldblum turning into a giant insect; and JG Ballard adaptation, Crash (1996), which explores the deadly erotic fascination of cars and boasts a notorious scene of a character having sex with a wound on a crash victim’s leg.

It’s hard not to feel a certain nostalgia for all these shock moments. Cronenberg was working during the heyday of “video nasties”. His movies invariably stir up very mixed reactions. There would always be some reviewers ready to pronounce him “vile” and to describe his work as sick “beyond the bounds of depravity”. At the same time, others would hail him as the latest follower in a grand cinematic tradition that stretched back to Un Chien Andalou (1929), the surrealist masterpiece directed by Louis Buñuel and Salvador Dali, which opened with a scene of an eyeball being sliced by a razor.

Cronenberg was a naturally subversive figure. He didn’t regard bodies in the same way as other filmmakers. “When I look at a person, I see this maelstrom of organic, chemical and electron chaos; volatility and instability, shimmering; and the ability to change and transform,” he once noted.

Even those who hated or disapproved of Cronenberg’s films were secretly frightened of his intelligence and vast frame of reference. He wasn’t just making exploitation movies. He was probing away at taboos and exploring how technology was changing both human behaviour and physiology itself. He was a poet of sexual mutation and disease. His films also had a macabre humour. As he acknowledged in an interview with author Serge Grünberg, he wanted to provoke audiences. “I don’t make a film to be loved…I’m looking for a kind of complex reaction. If someone is disturbed and angry, but somehow also seduced and attracted at the same time, then that’s something I would like.”

Until recently, though, it seemed that the Canadian director’s moment had passed. His ideas had been absorbed into the mainstream. Recent Marvel movies like Morbius (2022), in which a sickly scientist gains superhuman strength by absorbing the genes of vampire bats, and Venom (2022), with Tom Hardy being taken over by an alien parasite, had plot lines which, a generation ago, might have been found in Cronenberg stories, rather than in summer blockbusters.

Cronenberg himself appeared disillusioned with cinema. In interviews, he struck a strangely querulous, Mr Magoo-like note, saying that he had stopped going to the movies because he couldn’t find anywhere convenient to park. His more recent features, A Dangerous Method (2011) Cosmopolis (2012) and Maps to the Stars (2014), had moved away from exploding head-style body horror, instead exploring Freudian-era hysteria and the psychological neuroses of Hollywood film stars and hangers-on. He hinted that he might not make any more movies.

It is therefore heartening to see Cronenberg returning to the Cannes festival with a new feature, Crimes of the Future, which promises to be every bit as stomach-churning as the director’s bloodiest and most extreme early works. He has even filched the title and some of the themes from his own 1970 feature of the same name. The first Crimes of the Future was about a dermatologist on the run after killing off the “entire population of sexually mature women” with cosmetics that had lethal side effects.

“You fill me with a desire to cut my face open,” Léa Seydoux tells Viggo Mortensen in one of the clips included in the trailer for the new feature. Die-hard Cronenberg fans will be pleased to see the film has plenty of imagery of creepy-looking medical instruments piercing bodies and of scarred and bloodied flesh.

Mortensen plays an avant-garde performance artist who seems to deal in stolen organs. He has embraced “Accelerated Evolution Syndrome” which allows him to grow “new and unexpected organs in his body.” Seydoux is cast as his partner and Kristen Stewart is the investigator following their movements.

The horror fan sites are building this up as a film that will leave chaos and controversy in its wake. “The last 20 minutes are a very tough sit. I expect walk-outs, faintings and real panic attacks (I almost had one myself!),” an anonymous programmer recently told website World Of Reel after coming out, shell-shocked, from an early screening.

It would be a considerable achievement for Cronenberg, who turns 80 next year, to provoke as much outrage with his new film as with incendiary works like Rabid and Crash. These days, when he attends festivals, he is generally given lifetime achievement awards rather than threatened with bans. Nonetheless, his brand of body horror seems more relevant today than ever. In an era of pandemics, hacking, Artificial Intelligence, genetic engineering, deepfake videos, and extreme plastic surgery, the bizarre transformations that he used to show in his sci-fi films have become increasingly commonplace. In his 1999 film Existenz, long before Oculus headsets and the growth of VR gaming, Cronenberg posited the idea that video games could be plugged into their players’ nervous systems.

Laura Poitras’s recent short documentary Terror Contagion tells a contemporary story that could come straight from a Cronenberg movie. She investigates how Israeli technology group NSO Group Technologies’ Pegasus spyware is being used by repressive governments to harass and intimidate their critics. Once it gets inside their smartphones, their innermost secrets are revealed, just as those of many Cronenberg characters used to be when their bodies were infected with viruses or their DNA was tinkered with.

“What is really disturbing about this kind of digital violence is the link between the digital violence and actual real-world physical violence,” Poitras said of the Pegasus spyware when I interviewed her recently. Her words were chilling. She wasn’t talking about some futuristic sci-fi movie but about human rights activists targeted by hostile governments, intimidated, and sometimes, for example in the case of Jamal Khashoggi, actually killed.

There is a sense, then, that the real world is catching up with the ideas that Cronenberg was exploring several decades ago. The director, though, has long shown an ability for metamorphosis and re-invention matching that of his own movie characters. That is why such excitement is building around his new feature and its director’s timely return to the ever-fertile ground of true body horror. As he himself recently quipped, he still has “unfinished business with the future”.

‘Crimes of the Future’ screens in competition at the 75th Cannes Festival from 17 to 28 May 2022 (festival-cannes.com/en/)