We need to stop 'polaroiding' our Black youth with records. Let's give them a path to dream

“Reality is wrong. Dreams are for real” — Tupac Shakur

That’s a powerful statement from a young Black hip-hop and rap artist who died a violent death in Las Vegas in 1996 at the age of 25. Many would say he got it backwards. Some may recognize truth in his words.

The reality is that dreams are often thwarted for Black youth in our society. Many of them experience trauma regularly in communities that are riddled with gun and gang violence, incarceration, police brutality, oppression, depression, suicide, disease, poverty, neglect, etc. The reality they live in is wrong on many levels. The dreams they have are real yet may never be realized.

Previous Maxine Bryant column: This year, observe Juneteenth as a reminder that the living have a responsibility to keep living

Other Maxine Bryant columns: Learn from U.S. history — the Black vote matters. So show up at the polls in May.

Subscribe to The 912: Amplifying the Black community in Savannah, featuring Black stories, art, food and more

Consider, for example, youth in Chatham County who have been labeled as “designated felons." Their future seemingly has been sealed. Their reality is a label that marks them for life. That reality is wrong.

Designated felons are youth ages 13 and up who have committed an act that would be classified as a felony if committed by an adult. Designated felonies are categorized as Class A and Class B. Both include provisions for repeat offenders. One definition is “any act that would be a violent felony is considered a Class A Designated Felony, if the child has previously been adjudicated three times on felony charges.”

Recent jail stories: Cash bail is big business in Chatham County, but a Deep Center report shows the costs to taxpayers

The imagery that often comes to mind for youth labeled as designated felons are hardened young people (specifically Black male youth) who have committed heinous crimes: murder, aggravated assault with a weapon, etc. While there are some that indeed fall into this category, many have been labeled for getting into multiple fights. All too often, the behavioral choices of their youth haunt them for life.

Recently, I spoke with a 49-year-old Black male who served time as a youth from age 15 through 19. He exited the system, pursued, and obtained his education and is now a Ph.D. professor at a noted university. Yet, he has been unable to have his juvenile record expunged and many of his rights as a citizen elude him.

That reality is wrong. His dream to be free from society’s picture of him is real.

Former felons struggle to find jobs: 'You can become bitter or you can become better'

Student leader: America's incarceration problem demands policy solutions

The harms of terms such as ‘designated felon’ are many. First, it focuses on the individual and not the trauma contributing to his/her behaviors; secondly, it sets the youth up for “self-fulfilling prophecy” (when people become what they are told they are); and thirdly this designation potentially remains connected to a person for life. Instead of the list of crimes connected with this designation becoming smaller, it has ballooned, particularly in Chatham County.

In Chatham County, Black youth are disproportionately represented in our juvenile system. According to the REAL Task Force Report, 76% of the youth in Chatham County’s juvenile system are Black.

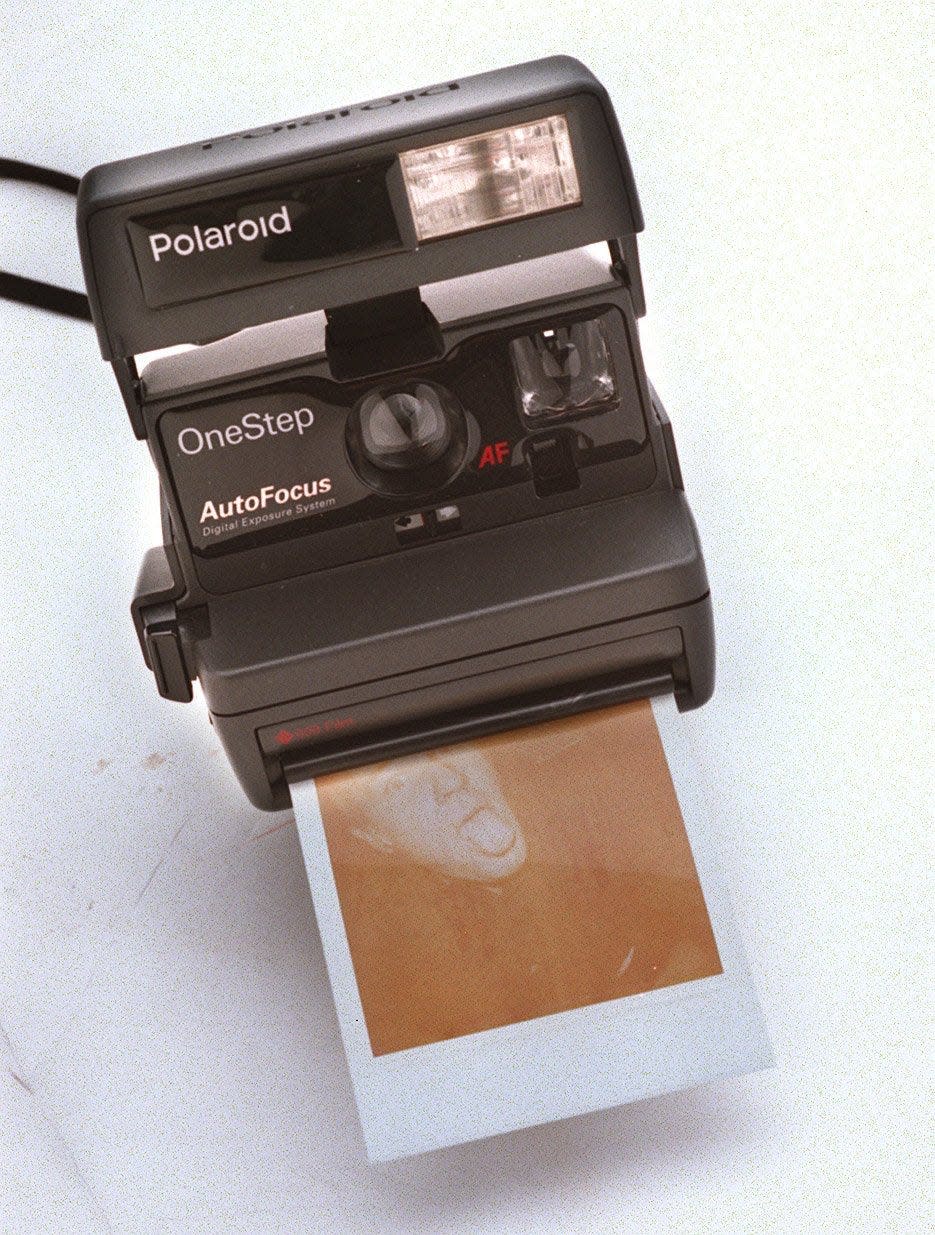

Remember the polaroid camera? We’d take a picture of a person and instantly the picture would eject from the camera with a covering over it. We’d shake the picture and pull back the covering. Voila! We’d have a captured picture of that moment. We couldn’t change it or edit it. That picture will always be the same

Too often that’s how we treat young people who make bad choices. We “polaroid camera” them. We put them into the frame of a “bad person”, a designated felon, a convicted youth – for life. We hold them hostage to a frame that captured the worst moments of their life. They are marked.

Nowadays, we have the capability to take pictures with our cell phones. Immediately we can edit the picture – change the background, remove a whole person from the picture, edit facial features, etc. We can instantly become picture editors. We can do that in life also! We can become societal picture editors by supporting youth to grow into responsible adults instead of branding them for life. The people I know who were able to turn their lives around following incarceration as a youth had strong supporters who provided guidance, encouragement, and love during their transition into responsible citizenship.

SMN reports: Former felons navigate the complexities of housing, employment and mental health in re-entry

A former gang member quoted in the 2020-2021 DEEP Center Annual Report puts it this way, “Youth can walk around trouble if there’s some place to walk to and someone to walk with."

Fortunately in Chatham County, there is a collaborative effort among several agencies that has shown promise in changing the trajectory of young people’s lives who have been labeled as “troubled," “at risk," or “designated felons." In 2017, the pilot Work Readiness Enrichment Program was launched by the juvenile court and relies on a partnership with Savannah-Chatham County Public School System, Goodwill, Frank Callen Boys and Girls Club, Head Up Guidance Services, and the YMCA of Coastal Georgia.

Each agency contributes a particular expertise combined often with tangible assets. This is a great example of parts of the “village” showing up.

According to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, which financially supported community safety forums that laid the foundation for the program, the Work Readiness Enrichment Program focuses on boys ages 14-16 “who have been charged with felony-level or multiple crimes and are disengaged or significantly behind grade level at school.” The pilot was promising, and plans were made to extend the length of the program and lay the foundation to sustain it.

Reality is wrong. Dreams are for real. These words can be flipped so that a right reality is created that makes good dreams real.

'Odds were pretty much against him': Creely's turbulent childhood shaped by drug addiction

How? An African proverb provides simple wisdom: “A child is what you put into him.”

When we sow trauma in troubled communities without addressing the cause, the child will grow up traumatized. When we sow hatred and prejudice, the child will grow up hating people who look like him/her and those who do not. When we sow love, understanding, and support, the child will grow up with a sense of self-love, full of esteem and able to sow positivity into others.

Here's the question: what will we sow into our youth? Let’s flip the script written by Tupac: Reality is right and positive. Dreams are meant to come true.

Maxine L. Bryant, Ph.D., is an assistant professor, Department of Criminal Justice & Criminology; director, Center for Africana Studies, and director, Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Center at Georgia Southern University. Contact her at 912-344-3602 or email dr.maxinebryant@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Black youth incarceration in Chatham County GA: How do we fix it