Stopping the 'madman': Rockport, Indiana woman to appear in PBS Vietnam documentary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

EVANSVILLE – When Mary Munchel saw the article about napalm, she knew she had to do something.

A mix of sticky gel and gasoline, the substance was all over Vietnam in 1969. The U.S. military weaved it into incendiary bombs and dropped it on villages and jungles, leaving it to adhere to the skin – so hot and poisonous that it could burn off your clothes, damage your organs and ultimately kill you.

Munchel read about it all in Ball State University’s underground newspaper. It shocked the undergrad to her core. How, she wondered, could America be doing this?

Working at an Indianapolis insurance agency during her summer break, she decided her co-workers should know what she knew. So she posted pictures of napalm victims in the company’s lunchroom.

Local history:25 years ago, Prince was slated to perform at an Evansville bar. He played pool instead

“My boss called me into his office and called me a communist. He told me he could fire me if he wanted to,” she said. “That reaction really pushed me further into thinking seriously we shouldn’t be in Vietnam.”

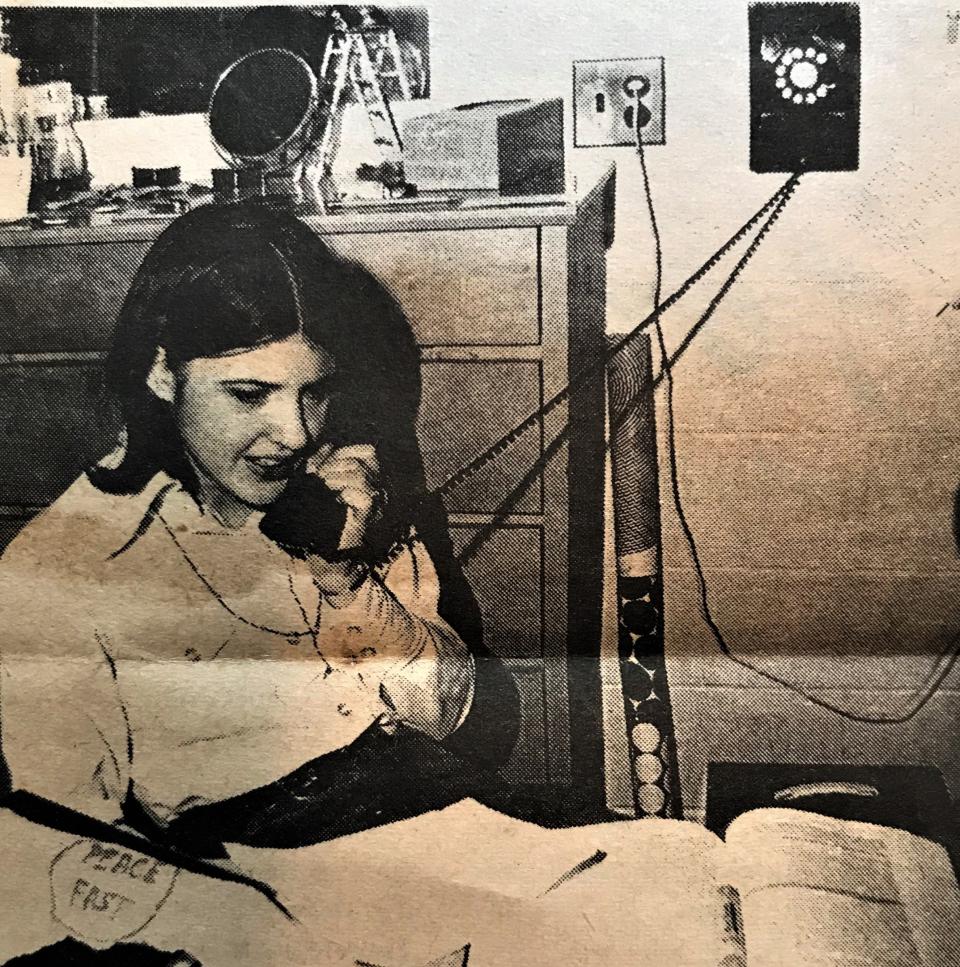

Within months, Munchel would become a key figure in Indiana’s growing antiwar movement. She organized Ball State’s chapter of the Vietnam Moratorium Committee, helped set up marches and protests in Muncie and beyond, and soon found herself as the centerpiece of an NBC news report, serving as a symbol of youth fighting back against “the establishment.”

More than 50 years later, her work will be part of the PBS Documentary “The Movement and the Madman,” which chronicles protesters’ efforts to prevent then-President Richard Nixon from using nuclear weapons in Vietnam. The multi-part film will premiere Tuesday, March 28.

Now Mary Posner after marrying her husband Lou, she’s spent decades working as a clinical psychologist in Rockport, Indiana. But her activism never left her. On the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam Moratorium Committee in 2019, she gathered some of her old compatriots and took part in a daylong conference at Ball State.

That led to an invitation to speak at a panel at George Washington University – which led to her giving a speech in front of the White House for the Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee.

And that led, finally, to the producers of “Madman” tracking her down for an interview.

“You just never know how one step is going to lead to another,” she said.

‘The Movement and the Madman’

That was certainly true of Posner’s activism.

When she arrived back at school in September 1969, she learned the national moratorium committee had planned its centerpiece event for Oct. 15. They were encouraging everyone to boycott their normal daily activities and instead spend their time protesting the war.

Posner thought a Ball State branch of the organization would work well. But there wasn’t much time to plan.

“I didn’t think I was that qualified to lead that, but I couldn’t find anyone else to do it,” she said. “So I jumped in.”

The turnout was modest – about 25 people carried signs on campus and read the names of the war dead – but other moratoriums around the country attracted scores more.

It was all happening in the shadow of one of the biggest antiwar marches in U.S. history. And it’s because of it and the moratorium, “The Movement and the Madman” claims, that Nixon abandoned plans to drop nuclear bombs on Vietnam.

The president had grown tired of the stalemate in Southeast Asia. According to journalist Seymour Hersh and others, he eventually put the North Vietnamese on notice.

Local life:Meet the 15-year-old budding violin virtuoso growing up on Evansville's West Side

If they didn’t give up South Vietnam by the end of 1969, he reportedly told them, “I’m going to hit you with everything I have.”

Called “Operation Duck Hook,” Nixon and his national security advisor Henry Kissinger drafted plans to escalate operations in Vietnam and prepare the United States’ nuclear arsenal for action.

As all this was going on behind closed doors, the antiwar movement was reaching a fever pitch. On Nov. 15 of that year, 500,000 protesters swarmed Washington as gobs more marched around the country – including in Muncie, where Posner and about 400 others gathered.

That uprising was one of the reasons Nixon balked, unearthed National Archive records show.

“Nixon began to doubt whether he could maintain public support” for something like Duck Hook, researchers at George Washington University wrote decades later.

‘Muncie’s anger’

Even after all that, Posner continued to protest, facing opposition on all sides.

The Ball State student newspaper wrote editorials against the local moratorium committee. A group called Project Faith collected signatures in support of Nixon. Even the campus leftists spoke out against her. To them, she wasn’t radical enough.

She eventually attracted the attention of the national press. After all, this was happening in “Middletown, USA” – the designation given to Muncie decades before in a series of sociological studies by Robert and Helen Lynd that cast it as the epicenter of conservative, prejudiced America.

And in 1969 and 1970, a story on NBC’s “Huntley-Brinkley Report” claimed, it had found its top antagonist.

Indiana news:Statehouse roundup: police buffer, permitless carry database, wetlands

“The revolutionary upon whom Muncie’s anger focused was Mary Munchel,” reporter Dean Brelis boomed.

The story, which aired in February 1970, chronicled the efforts from Posner and other protesters. Several times in November and December of 1969, they asked the city’s permission to hold demonstrations in front of the courthouse plaza. Each time, they were told the space was already taken by the local AmVets group for a “patriotic ceremony.”

One day, the two groups converged. As protesters carried a casket filled with the names of the war dead, the veterans staged 21-gun salutes every 10 minutes – their crackling firearms drowning out the voices of demonstrators.

“The gunfire was really vicious,” Posner told NBC. “At point one of the veterans said – we were raising our hands in the peace sign – ‘if you raise your hands any higher, we’ll shoot your fingers off.’”

AmVets chairman Fred McCllelan denied that ever happened. But he didn’t betray any semblance of sympathy for the protesters. He said their peaceful actions were worse than burning a draft card. And he told Brelis that if his own child ever protested, he’d punish him.

“He knows what this country stands for,” McCellelan said. “He knows why we’re in Vietnam and why we have to be there.”

Kent State and a new life

In the spring of 1970, Nixon began bombing Cambodia. And on May 4, 1970, – with a wall of National Guard soldiers looming – students at Kent State University gathered to protest. Some threw rocks at the soldiers, who responded by hurling tear gas canisters into the crowd.

At 12:24 p.m., things irrevocably escalated. Soldiers opened fire. Nine were injured. Four – Jeffrey Miller, Allison Krause, Willliam Schroeder and Sandra Scheuer – were killed.

The massacre sparked waves of anger and protest, and “emboldened” demonstrators for a time, Posner said. But that eventually soured.

“I guess we felt less like we really could make a difference at that point,” she said.

Realizing she needed to graduate, she left campus to finish her student teaching. Her time in the campus movement was over.

Local news:'We just want to give back:' After double shooting, Wildts to hold blood drive

That didn’t mean she stopped protesting. She met her husband, a Vietnam veteran named Lou Posner, later that year. While serving, he’d written an article decrying the war and sent it to a Ball State professor Mary happened to be working for.

Over the years, they continued their advocacy together. When they moved to Bloomington to allow Mary to pursue her psychology degree at IU, she and Lou led the Monroe County committee for the impeachment of Nixon.

More than five decades after that article on napalm sent Posner barreling toward activism, the state of protest is much different, she said. A fractured media makes it difficult for people to agree on basic facts, let alone individual principles. But she’s heartened by the efforts of people like Greta Thunberg and the students who survived the school shooting in Parkland, Florida.

She’s also proud of the younger self the documentary has allowed her to revisit.

“People go to college and party and have a good time, and I missed out on some of that,” she said. “I didn’t have much of a social life, and it caused some friction with people that I cared about. But I certainly don’t regret anything I did.”

Additional information from newspaper archives. Contact Jon Webb at jon.webb@courierpress.com

This article originally appeared on Evansville Courier & Press: Stopping 'Madman': Indiana woman to appear in PBS Vietnam documentary