The stories of Herbert Johnson and Brad Smith are important history. Here's how we told them.

SPOILER ALERT: This note divulges plot developments in the Legal Lynching series and is meant to be read after the stories.

Reporting of this story began in December 2022, while we were working on another story that required reading several years’ worth of Barrington Town Council meeting minutes.

Among those records was a July 7, 1931, entry:

“The Chief of Police was granted a leave of absence to go to Albany, N.Y. to assist and plead for the life of Herbert Johnson, a former resident of this Town, sentenced to die during the week of July 20th.”

We knew there had to be a story behind that! Our first stop: our own archives, which held the original stories of the chief's trip from 1931.

The reporting adventure that followed took us through dozens of hours of research at archives in Rhode Island, Massachusetts and New York State, plus dozens more searching online archives that covered those states, plus Connecticut, Ohio and Illinois.

In all, we reviewed thousands of pages of documents.

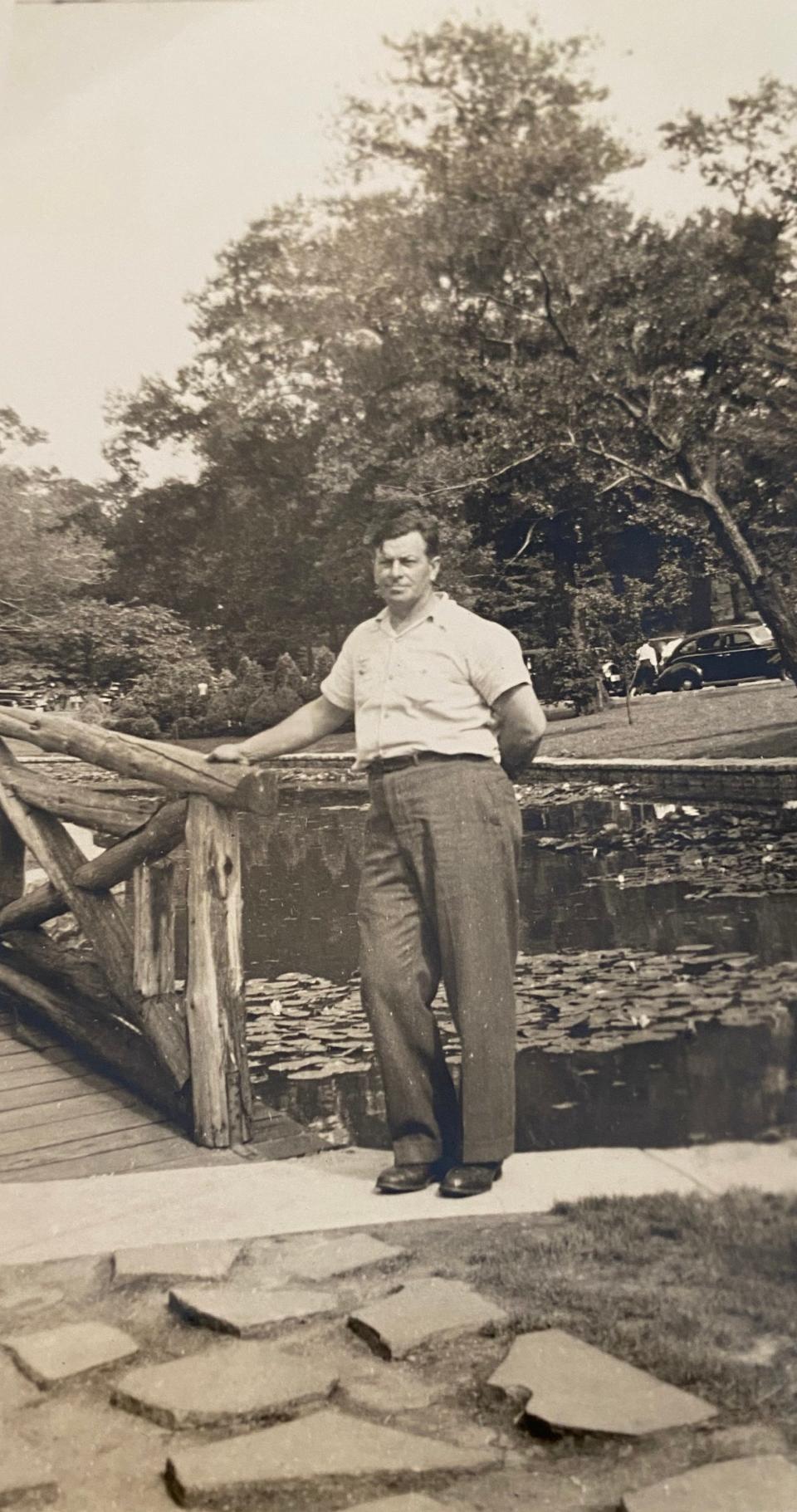

The reporting took us to the upstate New York courthouse where Sheriff Henry Steadman was shot, to the beach where Willie Egan was shot, and to the ravine where Herbert Johnson was captured.

We searched cemeteries in Barrington and Providence, looking for the elusive final resting place of Herbert Johnson, and visited cemeteries in Newport, Middletown, Central Falls, Barrington and Middleburgh, New York, for the graves of others mentioned in this series.

We read the files of newspapers covering Schoharie and Schenectady counties, New York; Pawtucket; Barrington; Warren; Fall River; Newport; Cleveland; Chicago; and Providence, which was served by several daily papers a century ago in addition to The Providence Journal and its sister paper, The Evening Bulletin.

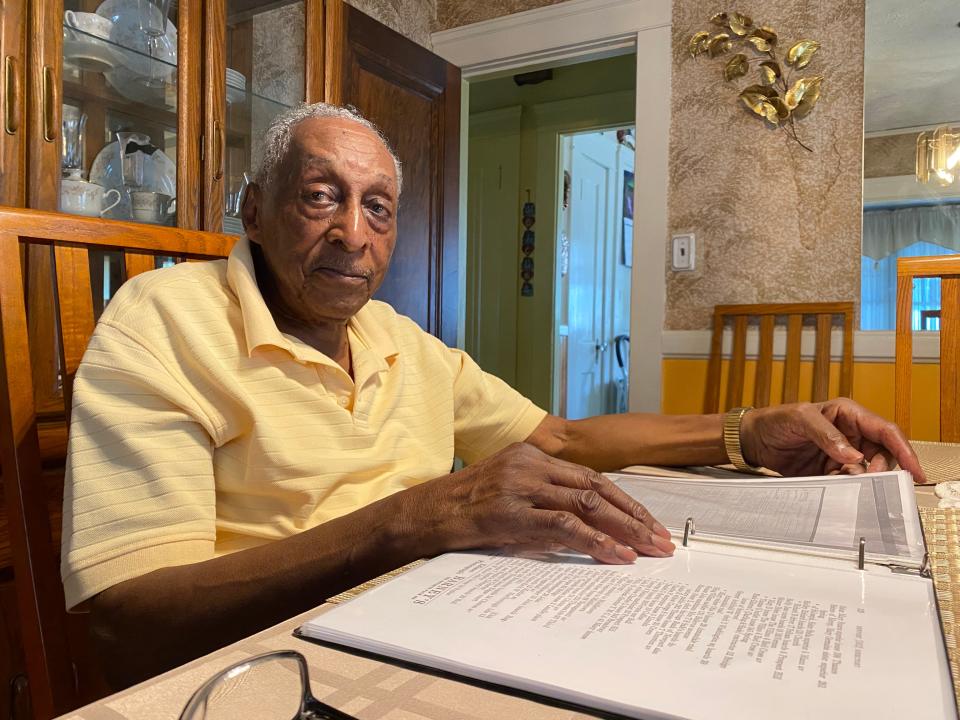

We met, in person or by phone, with relatives of Charles Bradley Smith, Herbert Johnson, Al Pearson and Robert Greene Elliott, the executioner who ended Johnson’s life.

We hunted down records of Brad Smith’s pardon, of Herbert Johnson’s time at the State Home and School, of police logs of Brad Smith’s near-lynching at Easton’s Beach and of Al and Angie Pearson’s divorces, including a handwritten letter from Angie to her first husband after she left town with Al.

We pored over court files in Pawtucket, Providence, Cranston and Newport, as well as Albany, New York.

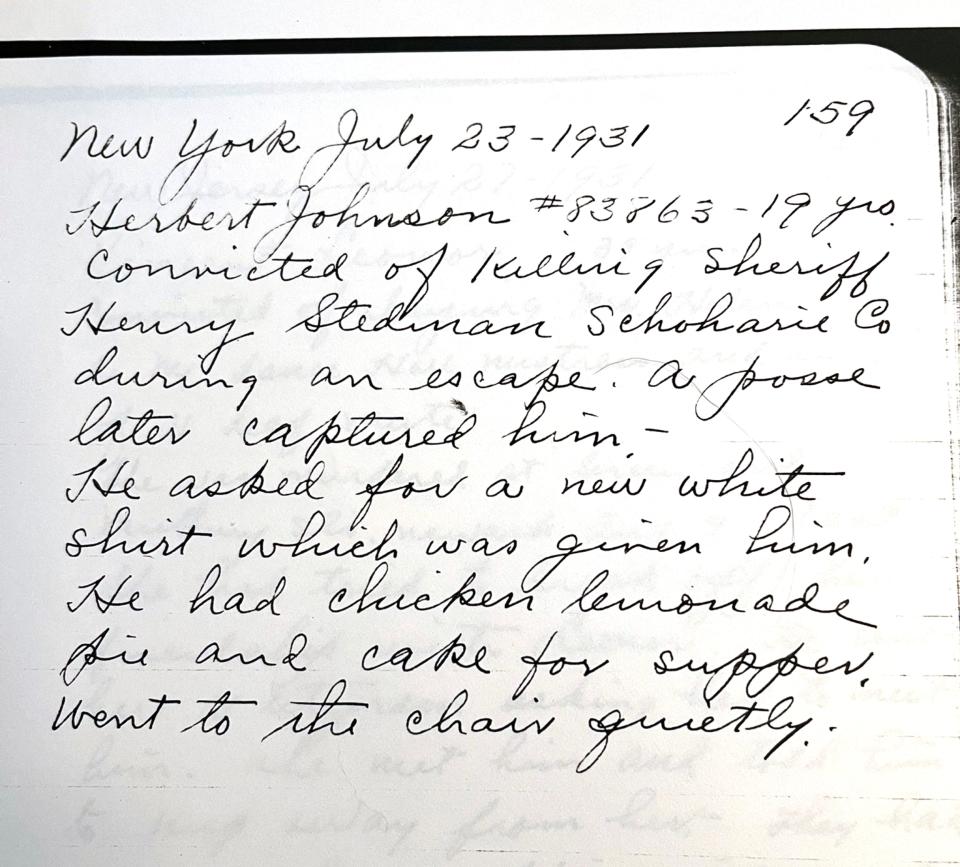

We read Herbert Johnson’s intake records from Sing Sing Prison and his entry in the execution diary.

We hiked through the woods and marshlands of Barrington, searching for the place Herbert Johnson once called home.

We took all that we learned and forged it into the stories of Herbert Johnson and Charles Bradley Smith. They are presented here as stories, the way they would have been recounted by those who were there, with little interruption to cite sources and discuss how we know what we know.

But nothing in this retelling of those stories has been invented. It all comes from contemporaneous accounts from the 1910s through the 1940s, as found in official records and newspapers, as well as the stories passed down to the families of those who lived them.

We would like to acknowledge a debt of gratitude to:

Barrington Town Clerk Meredith J. DeSisto, who repeatedly offered guidance with the town’s tax, cemetery, land, probate, vital and Town Council records.

Kenneth Carlson, of the Rhode Island State Archives, who helped with a host of records, but especially the Newport police log books from 1913, Charles Bradley Smith's pardon and Carlson's knowledge of where to find several records that were not in the state’s collection.

Andrew B. Smith, of the Rhode Island Judicial Records Center, who made repeated trips into the archives searching for historical case records relating to the Johnson, Smith and Pearson families.

Veronica Denison, special collections librarian at Rhode Island College’s Adams Library, repository of the records of the State Home and School, which were key to opening the story of Herbert Johnson’s early years.

Rebecca Valentine and her colleagues at the Rhode Island Historical Society for their help finding dozens of historical newspapers.

April L. Schmick, deputy chief clerk of the Schoharie County Supreme and County Courts, who showed us around the courthouse, including the room where Sheriff Steadman was shot.

Pete Lindemann, of the Cobleskill Times-Journal in Schoharie County, New York, who arranged local history contacts and who provided access to the paper’s bound archives.

Schoharie County Sheriff Ronald R. Stevens, who provided jail records and led a tour of the hills around Schoharie, New York, including the creek where Herbert Johnson was captured.

Anne Brannen, who provided a copy of entries from her great-grandfather’s executioner’s diary.

Cindy Elder, of the Barrington Land Conservation Trust, and a Barrington resident who wishes to remain anonymous, who facilitated access to the land where Herbert Johnson once lived.

Kaela Bleho, of the Newport Historical Society, for help finding photos of Charles Bradley Smith in the society’s Newport Daily News glass plate collection.

The City of Fall River; its city clerk's office, which helped sort out the mystery of Herbert Johnson's birth certificate; and its Board of Elections, which helped in the search for the truth about Beecher Taft, Herbert Johnson's purported father.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: How The Providence Journal reported and wrote the Legal Lynching series