As storms brew in the tropics, Wrightsville Beach nervously waits for its beach nourishment

A contract has been signed, and a winter window for the work has been set.

Now all Wrightsville Beach has to do is wait, with fingers crossed, that its beach can hold out for a few more months before it gets a fresh injection of sand.

The New Hanover County beach town has been waiting more than two years for crews to pump new material onto its main attraction. The delay has meant Wrightsville's eroded beach, especially the section between the town's two piers, this summer has had to weather a glancing blow from Hurricane Idalia, swells from powerful Hurricanes Franklin, Lee and Nigel as they moved north well offshore, several bouts of King Tides, and more heavy surf from Tropical Storm Ophelia late last week that brought frothy waves and blustery conditions to the region's beaches.

SURF'S UP! PHOTOS: As Idalia nears Wilmington, surfers enjoy swells from Hurricane Franklin

And hurricane season still has more than two months to run, ending Nov. 30.

But so far, town officials have said the dunes appear to be holding aside from some scouring and a few overwashing events during Hurricane Idalia.

Why was the nourishment delayed?

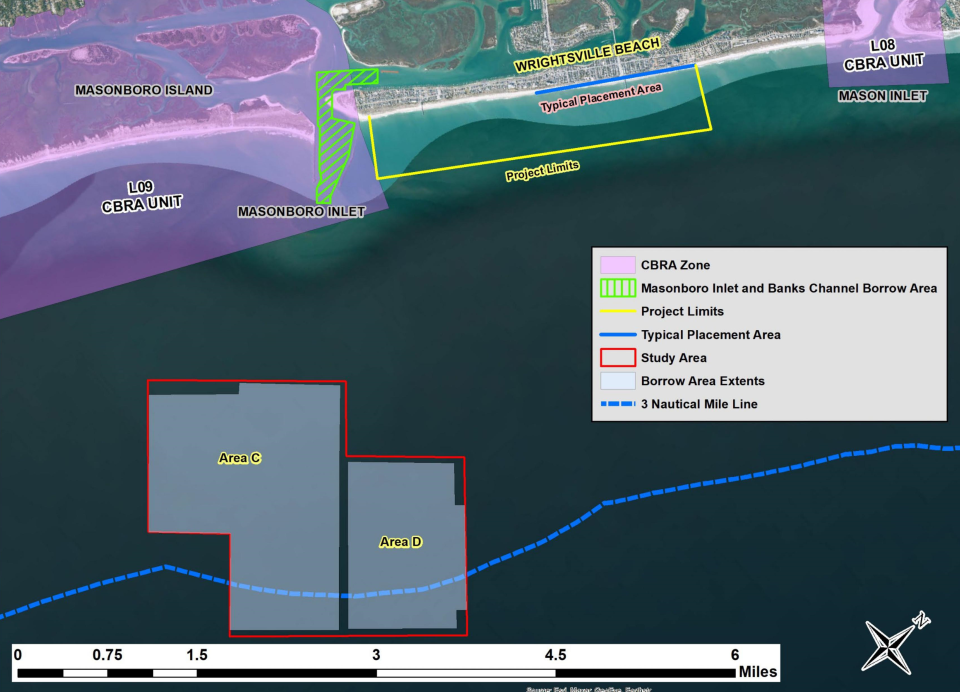

What had been a skirmish over language broke out into a full-fledged sand war in 2021 when the Biden administration decided to enforce a rule that prohibits sand from federally designated Coastal Barrier Resources Act (CBRA) zones, like Masonboro Inlet, from being used for projects outside the zone. The CBRA zone designation is meant to prohibit expenditure of federal dollars on projects in hazardous coastal areas.

Since the 1960s, Wrightsville Beach has dredged sand from Masonboro Inlet, which separates the beach town from undeveloped Masonboro Island, every three years to boost its engineered beach to better deal with the daily wave action and larger erosion events tied to hurricanes and nor'easters.

SAND WARS Wrightsville Beach wants Masonboro Inlet sand for nourishment. Feds say birds need it more

But environmentalists have said using sand from CBRA zones for beach nourishments violates the spirit of the law and keeps protected areas protected as important coastal habitats and as vital buffers for communities facing increased risk from stronger storms fueled by climate change.

Without access to the inlet's sand, Wrightsville Beach would have to go looking offshore for sand − a move that would require jumping through several regulatory hoops to make sure the sand was safe to be mined and pumped onto the beach.

What changed?

This summer the Army Corps of Engineers announced it was issuing an "emergency exception" to allow Wrightsville Beach to circumnavigate the CBRA ban and use sand for its beach from its historical Masonboro Inlet borrow area.

The move came after local officials pressured the federal government to approve a waiver because of the precarious state of Wrightsville's beach, the potential safety threat to people, property and vital infrastructure from erosion and overwash events, and the historical use of the inlet sand in the past. But corps' officials stressed that granting the waiver was a one-time exception, with future nourishments having to meet the same criteria to use sand from the inlet again.

What happens now?

Earlier this month the corps awarded a $13.6 million contract to Marinex Construction for the nourishment project.

Assuming the project doesn't run into anymore regulatory or financial hurdles, the corps expects the nourishment to take place during this winter's environmental dredging window which runs from mid-November through March 2024.

Unlike past nourishments of Wrightsville, Carolina and Kure beaches, this project also will be 100% federally funded. That's in large part thanks to U.S. Rep. David Rouzer, R-N.C., who secured the full federal funding in response to Wrightsville's project getting so delayed. Historically, the federal government pays for two-thirds of a federal nourishment project with state and local sources contributing the rest.

The congressman also has submitted a bill that would allow beach towns to keep using historical sand sources within CBRA zones.

RISING RISK A warming ocean is helping a flesh-eating bacteria creep north. What it means for the NC coast.

Reporter Gareth McGrath can be reached at GMcGrath@Gannett.com or @GarethMcGrathSN on Twitter. This story was produced with financial support from 1Earth Fund and the Prentice Foundation. The USA TODAY Network maintains full editorial control of the work.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Wrightsville Beach nourishment project approved after two year delay