Astronomers Are Stumped by New High-Frequency Wave on the Surface of the Sun

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

Astronomers have discovered a bizarre, new high-frequency wave on the surface of the sun.

☀️ You love space. So do we. Let’s nerd out over it together.

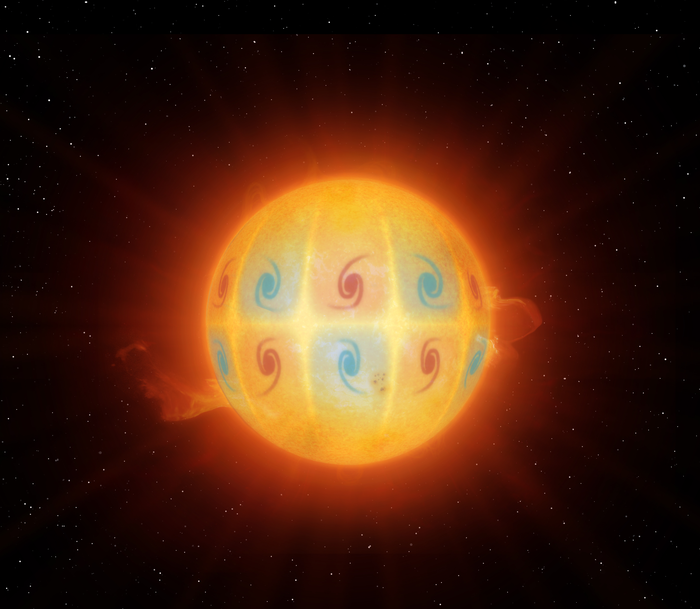

These acoustic waves, which astronomers spotted within a dataset spanning 25 years of observations by both space and ground-based observatories, travel three times faster than predicted by current theory. On top of that, the waves also form vortices that swirl in the opposite direction of the sun’s rotation.

A team of researchers from New York University, New York University Abu Dhabi’s Center for Space Science, and the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Mumbai, India, described the high-frequency retrograde (HFR) waves in a paper published March 24 to the journal Nature Astronomy.

Other types of waves are driven, in part, by magnetism, gravity, or convection, but that doesn’t seem to be the case with these newly discovered acoustic waves. Something else is powering them. (Curiously, similar high frequency waves have been observed in the ocean, the researchers explain, and atmospheric scientists have not yet uncovered their origins either.)

“If the HFR waves could be attributed to any of these three processes [gravity, magnetism, and convection], then the finding would have answered some open questions we still have about the Sun,” Chris S. Hanson, a research associate at New York University Abu Dhabi’s Center for Space Science said in a press statement. “However, these new waves don’t appear to be a result of these processes, and that’s exciting because it leads to a whole new set of questions.”

Astronomers study acoustic waves like these because we’re a long way from developing technology capable of peering deep into the sun’s interior. Still, scientists have gathered an unprecedented amount of data about our closest celestial neighbor. The next decade promises to be an even more exciting time for heliophysics—or the study of how the sun interacts with other bodies in the solar system.

In 2018, NASA launched its Parker Solar Probe—named for the late solar physicist Eugene Parker—from Florida’s space coast. Over the course of its seven-year mission, the spacecraft will get closer to the sun than any other spacecraft in history. Just four years in, it’s already broken speed records (Parker’s max speed is 430,000 mph) and made a series of surprising discoveries about solar winds, high-energy particles, and more.

Then, in February, 2020, the European Space Agency launched its Solar Orbiter probe, which the agency designed to study space weather; the heliosphere, or the protective plasma bubble that encases our solar system; and the sun’s poles, a mysterious region that has so far been understudied.

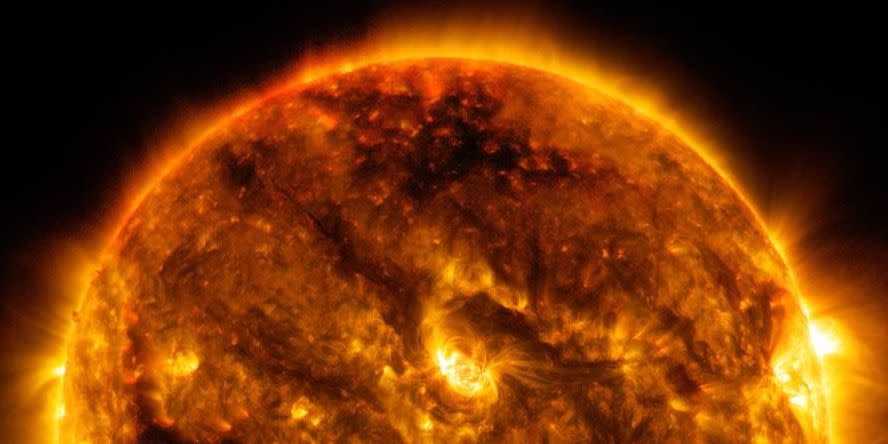

Just six months after it launched, the spacecraft managed to snap the closest-ever image of the sun. This image, in particular, revealed the presence of tiny solar flares, dubbed campfires, which could explain one of the most intriguing solar mysteries: why the sun’s corona—or the outermost layer of the sun's atmosphere—is hotter than its surface.

We’re entering a bright and—dare we say it—shining new era of solar science. The discoveries these observatories make could help researchers better predict destructive space weather and understand how the sun’s cycles impact physical processes here on Earth.

And that’s just the beginning.

You Might Also Like