The Strange Tale of Darwin and Kidnappers at the ‘Bottom of the World’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Most know that Charles Darwin was sailing aboard HMS Beagle when he made his famous call at the Galápagos, the remote Pacific archipelago that legend associates with his famous theory of evolution. Fewer, however, realize that the Beagle's five-week visit to the Galápagos belonged to a five-year (1831-36) global voyage conducted for survey, mapping and only inadvertently scientific purposes. Darwin, then in his early twenties, played no formal role on the voyage but had been invited to join it to serve as a dinner conversation partner on natural-history topics for Robert FitzRoy, the ship’s captain. In late 1832, the Beagle called at Tierra del Fuego, at “the bottom of the world,” for the purpose of repatriating three “Fuegians,” natives of that isolated realm, inadvertently kidnapped on an earlier Beagle surveying expedition commanded by FitzRoy and taken to England for a year of “civilizing” by English tutors.

In the below excerpt from Tom Chaffin’s Odyssey: Young Charles Darwin, the Beagle and the Voyage That Changed the World, the naturalist grapples with an episode that would leave a profound mark on his evolving view of the world.

By 1832’s final weeks, Captain FitzRoy’s thoughts had turned toward the Tierra del Fuego survey and repatriating the three Fuegians there. The afternoon of December 10, early summer in those austral climes, thus found his ship scudding along with a “strong breeze,” approaching Port Desire on southern Patagonia’s Atlantic coast.

Two days later, however, what Darwin called “the heaviest squall I have ever seen” battered the ship. And though it was early summer in that latitude, “the air has the bracing fear of an English winter day.” Further confounding expectations, three days later, the fifteenth, found the Beagle, sailing under “very foggy” conditions. “Every thing,” Darwin complained, “conspires to make our passage long.”

But the Beagle persevered; and, on Sunday, December 16, south of Cape St. Sebastian but still in Atlantic waters, “We made the coast of Tierra del Fuego.” A few men aboard that day had been on the ship’s earlier visits to Tierra del Fuego. But, noted Darwin, “The Beagle had

never visited this part before; so that it was new to every body.” No one aboard thus knew whether the area was inhabited.

But the mystery soon lifted. “Our ignorance whether any natives lived here, was soon cleared up by the usual signal of a smoke,” Darwin wrote. Furthermore, FitzRoy recalled, Natives soon appeared on the shore, calling across the bay’s waters, “waving skins, and beckoning to us with extreme eagerness.”

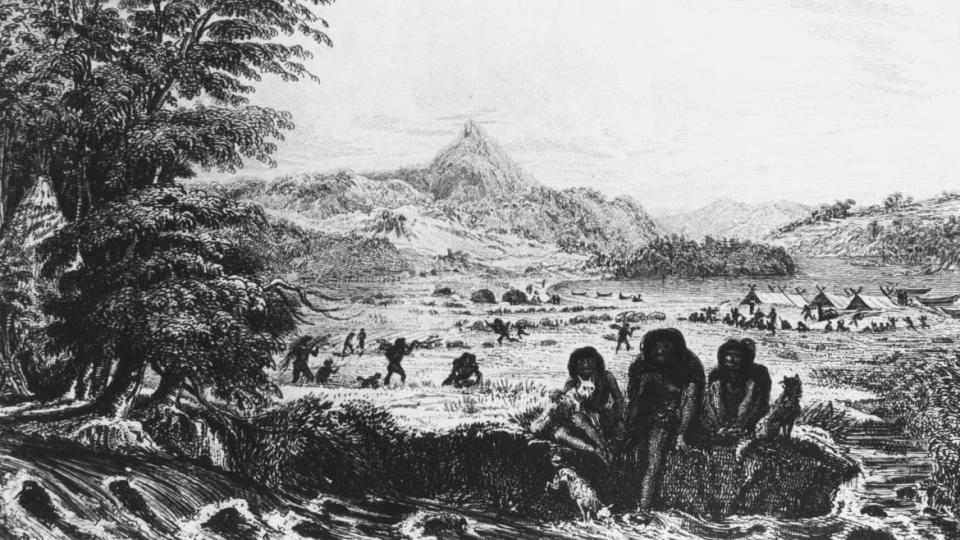

Fuegians at Woollya with the Fitzroy expedition's camp in the background in 1831.

Explorer Ferdinand Magellan, in 1520, reputedly named the archipelago Tierra del Fuego (“land of fire”) after the torches that Indigenes brought to the islands’ shores as his ships passed. Now, three centuries later, the Beagle’s officers, squinting into spyglasses, could clearly “see a group & some scattered Indians evidently watching the ship with interest.” Speculated Darwin, in his diary, “They must have lighted the fires immediately upon observing the vessel, but whether for the purpose of communicating the news or attracting our attention, we do not know.”

Later, recalling that first sighting to Caroline Darwin, Charles elaborated,

An untamed savage is I really [I] think one of the most extraordinary spectacles in the world. The difference between a domesticated & wild animal is far more strikingly marked in man. In the naked barbarian, with his body coated with paint, whose very gestures, whether they may be peacible or hostile are unintelligible, with difficulty we see a fellow-creature. No drawing or description will at all explain the extreme interest which is created by the first sight of savages.

English naval officer and meteorologist Robert Fitzroy who circumnavigated the globe in HMS Beagle in 1831 accompanied by Charles Darwin.

More admiringly, FitzRoy reflected, “I have often been astonished at the rapidity with which the Fuegians produce this effect (meant by them as a signal) in their wet climate, where I have been, at times, more than two hours attempting to kindle a fire.”

**

Terra del Fuego, at the “Bottom of the World,” occupied an austere, even terrifying, zone in the European imagination. For centuries of Old

World–born travelers, the archipelago constituted a realm beset with real and imagined perils—ship-pulverizing storms, disorienting labyrinths of channels and islands, starvation and cannibalism, nightmarish cold and darkness, and suicide-inducing isolation. Bearing witness to those dan- gers, European travelers left place-names there that doubled as cautionary tales: Desolation Bay, Fury Bay, Devil Island, Useless Bay, Port Famine.

Situated between Latitudes 52° and 56° South, the archipelago sprawled over 28,000 square miles, an area roughly the size of Ire- land. The Strait of Magellan separates Terra del Fuego from the South American mainland. Isla Grande, the archipelago’s (and South America’s) largest island, dominates its east and north, where the terrain tends to be relatively low-lying. In the west, geologically an extension of the Andes,

several mountains exceed 7,000 feet.

**

As the Beagle sailed south on December 17, a “strong wind” and obliging tides blessed its passage. “But even thus favoured,” Darwin noted, “it was easy to perceive how great a sea would rise were the two powers opposed to each other. The motion from such a sea is very disagreeable; it is called ‘pot-boiling’, & as water boiling breaks irregularly over the ships sides.” Hugging the coast, the Beagle passed “high hills clothed in brownish woods [which] take the place of the [earlier passed, steep] horizontal formations.” Still further south, now along Isla Grande’s east coast, the ship, that afternoon, entered a bay whose history and name evoked safe

anchorage—the Bay of Good Success.

On December 17, 1832, when the Beagle reached the bay, the days were growing longer, though not always brighter. Indeed, a “gloomy” sky hung over the cape’s waters at the next daybreak, at just after 3:00 A.M.

The scene captivated Darwin: “The country is not high, but formed of horizontal strata of some modern rock, which in most places forms abrupt cliffs facing the sea. It is also intersected by many sloping vallies.

These are covered with turf & scattered over with thickets & trees, so as to present a cheerful appearance.” In the distance, to the south, rose “a chain of lofty mountains, the summits of which glittered with snow.”

“Here,” noted Darwin, “we intend staying some days.” FitzRoy’s deci- sion to linger in the bay notwithstanding, the Beagle’s crew was already aware they were not alone. Earlier that day, while entering the bay, they had noticed, “a party of Fuegians . . . watching us.” The observers were “perched on a wild peak overhanging the sea & surrounded by wood.”

As we passed by they all sprang up & waving their cloaks of skins sent forth a loud sonorous shout. This they continued for a long time. These people followed the ship up the harbor & just before dark we again heard their cry & soon saw their fire at the entrance of the Wigwam which they built for the night. After dinner the Captain went on shore to look for a watering place; the little I then saw showed how different this country is from the corresponding zone in the Northern Hemisphere.

When Darwin later that day, still December 17, joined the captain to go ashore to search for freshwater sources, the young naturalist was weeks away from his twenty-fourth birthday. Over those hours and the coming days, that looming milestone prompted reflections on the physical distances he’d traveled over the past twelve months.

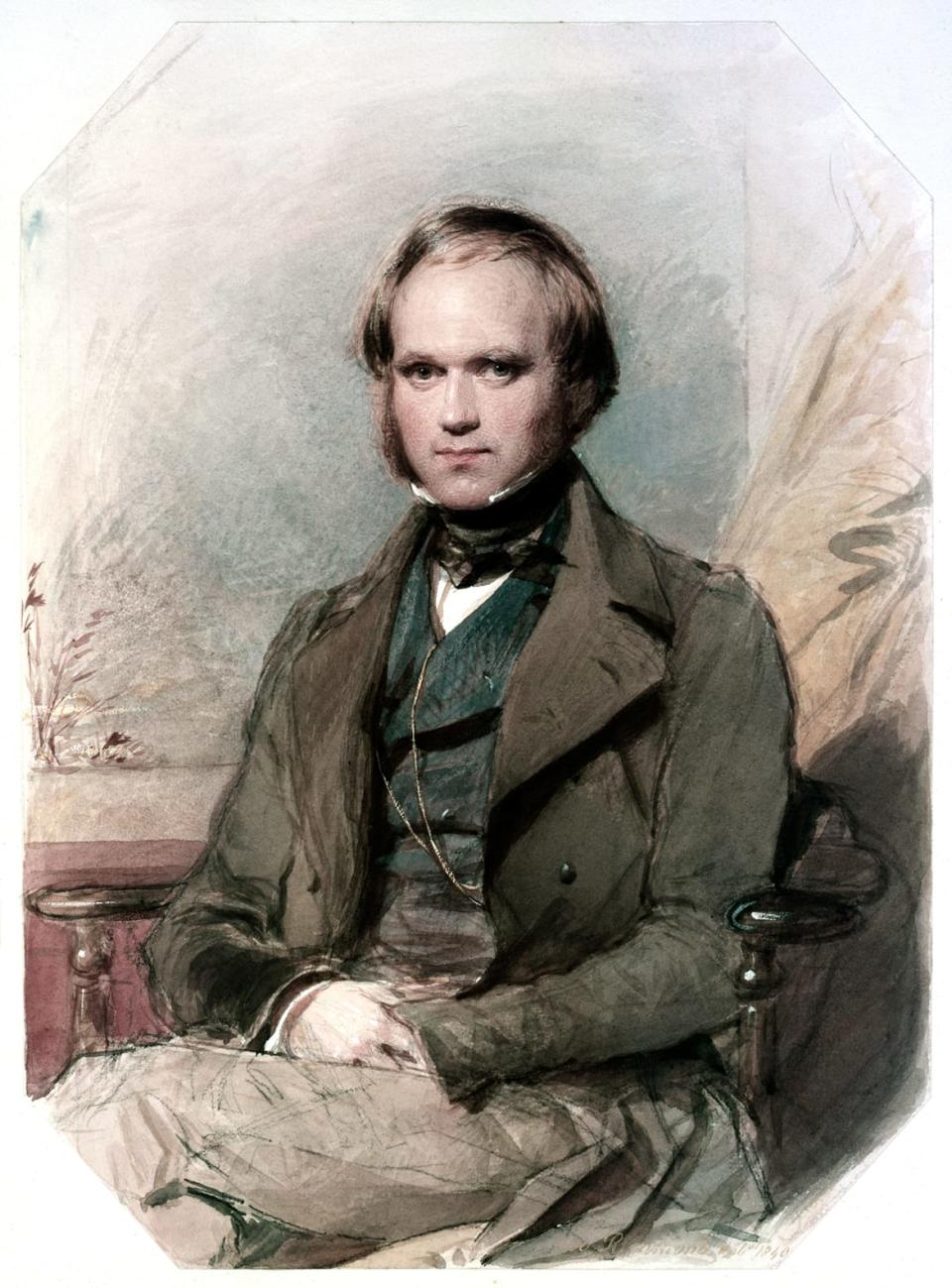

A young Charles Darwin in 1840.

Far from Shrewsbury, he was now journeying in the paths of explorers whose adventures he’d marveled over as a boy in books, such as C. C. Clarke’s Hundred Wonders of the World. Indeed, the Bay of Good Success in which the Beagle lay anchored, named by explorer García de Nodal, had been later visited by, among other celebrated travelers, English explorer James Cook. “To me it is delightful being at anchor in so wild a country as Tierra del F.,” Darwin reflected. “The very name of the harbor we are now in, recalls the idea of a voyage of discovery; more especially as it is memorable from being the first place Capt. Cook anchored in on this coast.”

More prosaically, Darwin described the bay as “a fine piece of water & surrounded on all sides by low mountains of slate.” Some of the land- scape’s features even brought to mind the Welsh mountains in which sixteen months earlier he assisted Professor Sedgwick’s fieldwork. “These are of the usual rounded or saddle-backed shape, such as occur in the less

wild parts of N: Wales. They differ remarkably from the latter in being clothed by a very thick wood of evergreens almost to the summit.”

That night, a gale rose from the shoreward mountains—pounding with wind and rain the Beagle, swinging at anchor in the bay. Inside, meanwhile, just above the ship’s stern, Darwin, snug in his cherished poop cabin, found ironic comfort in the vessel’s rocking, and the creaking of its wooden planks, in the storm-roiled waters. Drifting in and out of sleep in his hammock, he found added solace in the bay’s name and history.

Those who know the comfortable feeling of hearing the rain & wind beating against the windows whilst seated round a fire, will understand our feelings: it would have been a very bad night out at sea, & we as well as others may call this Good Success Bay.

**

The next day, December 18, FitzRoy, seeking to establish direct contact with the Fuegians, dispatched a boat to the shore, its passengers including Darwin, the Fuegian Jemmy Button, and several officers. The encounter began amicably. “As soon as the boat came within hail,” Darwin recalled, “one of the four men who advanced to receive us began to shout most vehemently, & at the same time pointed out a good landing place.”

By the time the Englishmen dragged their boat ashore, however, the women and children had scurried away. The remaining men on the beach “looked rather alarmed, but continued talking & making gestures with great rapidity. It was without exception the most curious & interesting spectacle I ever beheld.” Then, returning to a familiar theme, Darwin added, “I would not have believed how entire the difference between savage & civilized man is. It is greater than between a wild & domesticated animal, in as much as in man there is greater power of improvement.”

Apparently, the group the Beagle party saw was a family—its patriarch, an old man who remained on the shore. Beside him stood three “young powerful men,” each “about 6 feet high.” “From their dress &c &c,”

Darwin was taken aback—to him, the four resembling, “Devils on the Stage,” from Carl Maria von Weber’s 1821 opera Der Freischütz, which he’d seen in Cambridge.

The old man had a white feather cap; from under which, black long hair hung round his face. The skin is dirty copper colour. Reaching from ear to ear & including the upper lip, there was a broard red coloured band of paint. & parallel & above this, there was a white one; so that the eyebrows & eyelids were even thus coloured; the only garment was a large guanaco skin, with the hair outside. !is was merely thrown over their shoulders, one arm & leg being bare; for any exercise they must be absolutely naked.

For their part, the Fuegians seemed equally startled by the Europeans’ appearance. To assuage their fears, the Beagle’s men offered pieces of red cloth which, Darwin noted, “they immediately placed round their necks.” Right away, “We became good friends,” he recalled. “This was shown by the old man patting our breasts & making something like the same noise which people do when feeding chickens.”

I walked with the old man & this demonstration was repeated between us several times: at last he gave me three hard slaps on the breast & back at the same time, & making most curious noises. He then bared his bosom for me to return the compliment, which being done, he seemed highly pleased.

The parties tried to converse but to no avail. (“Their language,” Darwin noted dismissively, “does not deserve to be called articulate: Capt. Cook says it is like a man clearing his throat.”) As both groups soon resorted to pantomime, the Englishmen inferred that the Fuegians wanted knives. “This they showed by pretending to have blubber in their mouths, & cutting instead of tearing it from the body.”

But no knives were proffered that day. Still later, the Beagle’s men were reassured that the Fuegians apparently recognized the power of the firearms

they carried. “They knew what guns were & much dreaded them,” Darwin noted. And “nothing would tempt them to take one in their hands.”

**

During their December 18 encounter with the Fuegians at Good Success Bay, meanwhile, the Beagle’s Englishmen took particular notice of exchanges between Button and the Natives. Button, after all, was dressed in English clothes and spoke with the Beagle’s Englishmen in their native tongue. But, noted Darwin, observing Button’s interactions with the Indi- genes on the beach, “It was interesting to watch their conduct to him.” And without knowing the language of the Fuegians standing before him, Darwin nonetheless deduced their apparent entreaty to Button:

They immediately perceived the difference & held much conversation between themselves on the subject. The old man then began a long harangue to Jemmy; who said it was inviting him to stay with them: but the language is rather different & Jemmy could not talk to them.

The Beagle party’s first encounter with the Fuegians eventually concluded. But later that same day, after dinner, Darwin returned to the

same spot on the shore—with a party that now included Captain FitzRoy, midshipman Robert Hamond, missionary Richard Matthews, and the Fuegian York Minster—older than Button and by then in or approaching his life’s third decade. !is time, Darwin recalled, “They received us with less distrust & brought with them their timid children.” Taking note of Minster, “[t]hey examined the color of his skin; & having done so, they looked at ours. An arm being bared, they expressed the liveliest surprise & admiration. Their whole conduct was such an odd mixture of astonishment & imitation, that nothing could be more laughable & interesting.”

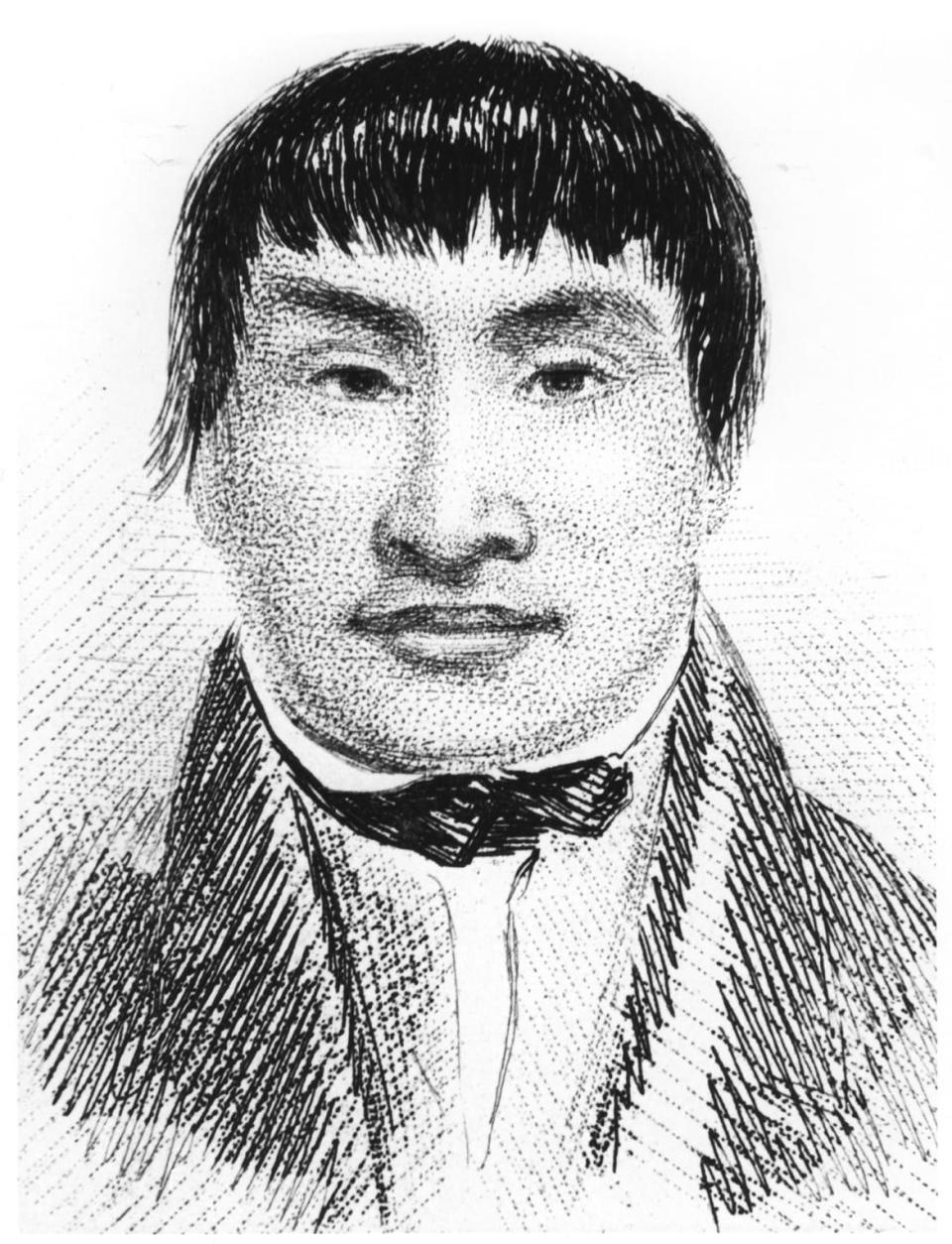

York Minster, a Fuegian 'adopted' by the expedition, as he appeared in 1832.

FitzRoy, describing the Fuegians assembled on the shore, recalled, “five or six stout men, half-clothed in guanaco-skins,” nearly six feet in height “and confident in demeanour.” “Except in colour and class of features,” he recalled, they bore no resemblance to the three Fuegians aboard the Beagle. Recalled FitzRoy, “I can never forget Mr. Hamond’s earnest expression, ‘What a pity such fine fellows should be left in such

a barbarous state!’”

Hammond’s comment, FitzRoy recalled, “told me that a desire to benefit these ignorant, though by no means contemptible human beings, was a natural emotion, and not the effect of individual caprice or erroneous enthusiasm.” More personally, the captain reflected, Hammond’s “feelings were exactly in unison with those I had experienced on former occasions.” And those sentiments led to the remorse that, in turn, “had led to my undertaking the heavy charge of those Fuegians whom I brought to England.”

Whimsically turning the tables, FitzRoy later compared the impression the Fuegians left that day on the Beagle’s men to that left at Dover, England, in 55 BCE, by native Britons, on Julius Caesar and his cohort, the first official representatives of the Roman Empire to arrive on British shores.

“Disagreeable,” FitzRoy wrote, “indeed painful, as is even the mental contemplation of a savage, and unwilling as we may be to consider our- selves even remotely descended from human beings in such a state, the reflection that Cæsar found the Britons painted and clothed in skins, like these Fuegians, cannot fail to augment an interest excited by their childish ignorance of matters familiar to civilized man, and by their healthy, independent state of existence.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.