Stress, low pay, uncertainty drove these Pa. teachers away from a profession they loved

Timothy Gleason trained to become an educator under the dark dome of a planetarium, as he taught a new generation how to gaze at the stars.

His original aspiration had been astrophysicist, but while he was in college for that degree, he led a few fellow students on telescope tours of the night sky at a nearby observatory. The small brush with teaching, he said, changed the course of his professional life.

Sharing knowledge with people seemed like more fun than tinkering with computer code all day, he concluded. So Gleason tweaked his major, fulfilled his student teaching requirement at a planetarium and landed a one-year post as a ninth-grade substitute teacher in the Keystone Central School District in Lock Haven.

The first sign of trouble with his new gig happened when he checked out the supply cabinets.

Many of the science supplies were dry-rotted, he recalled, and when he tried to test out one of the lab syringes, it emitted a puff of dust. Convinced he’d stumbled into the wrong place, he asked his colleagues where he could find the real supply closet.

“Obviously, I found the wrong one,” he thought at the time. “And the other teachers were basically like, ‘Oh you sweet summer child. No, that’s it.’”

After an exasperating year, Gleason ended up leaving his post, landing a job outside of teaching that afforded him more resources and involved less stress.

But while he’s found a personal solution, Pennsylvania’s school leaders and policymakers are still working to address the challenges he faced in the classroom. According to education experts, these same dynamics are causing other teachers to walk away or discouraging college students from pursuing the profession in the first place — fueling a teacher shortage that is afflicting schools across the commonwealth.

Pennsylvania’s teacher shortage is hard to quantify and understand because of gaps in data about where the need is most acute, according to a recent report on this challenge. However, the number of teaching certificates issued in the commonwealth has plummeted by roughly 73% from 2010 to 2021, while the number of emergency instructional permits has spiked by more than 200%, according to the Pennsylvania State Education Association.

“The commonwealth is not producing enough teachers to meet demand, and, as a result, we do not have enough caring, qualified adults in our school buildings to address the many challenges our students face,” Rich Askey, president of the Pennsylvania State Education Association, said in a recent press release.

People aren’t attracted to teaching because of the relatively low pay, stressful and isolating working conditions, inadequate mentoring and preparation and declining societal status, stated the recent report from Teach Plus Pennsylvania and the National Center on Education and the Economy.

State policymakers are advancing a slew of proposals to remedy the shortages, with proposals to raise the minimum teaching salary, create programs to forgive student loans for educators and establish scholarships for paraprofessionals who want to become teachers.

These solutions, though, will come too late for former educators like Gleason.

Coins for school supplies

Gleason’s second clue that trouble was ahead arrived shortly after the supply closet experience, when he dashed into the school office to photocopy his class syllabus. Upon entering the room, he discovered another teacher perched on a desk, stashing printer paper into the drop ceiling.

He told Gleason he was preparing for the lean days to come; the school had purchased a certain amount of paper for the year, he said, and there was no money to buy more when it ran out.

“Trust me,” the teacher told him, “by the end of the year, you’re gonna need to know that this is here.”

Gleason said his colleague’s predictions proved to be accurate — and the need for classroom materials extended far beyond paper. He remembers spending many afternoons after work shopping for pencils and other basic supplies at Walmart to restock his classroom.

At the time, his wife was still in college, and the couple was depending solely on his income. The trips to Walmart put an added strain on their already tight budget.

It got so bad that finding a roll of quarters underneath his bed made him feel like he’d “struck the jackpot.”

Toward the end of the year, Gleason recalls a series of events that formed the final straw for him. The district decided to lay off the most recently hired teachers to close a budget shortfall, sending waves of anxiety through the schools.

More: Inside this year's fight over Pa. school board seats and what happens in the classroom

On top of that, his students were growing restless after their standardized exams were complete. Gleason remembers that one day while getting ready for class, one student chucked a whole orange toward the front of the room, and it landed with a splat on the white board. Gleason said he was so burnt out by that point that instead of figuring out who had thrown the orange, he wiped the juice off the board and kept going as if nothing had happened.

One day, a friend texted him about a job in the science outreach office at Penn State University, and Gleason sent in his resume right then and there. He’s been working the new job, which still allows him to do some teaching, for the last five years, and he has no regrets about making the switch.

“I still get to work with kids. I still get to do education,” he said. “The pay is about the same, but if I’m not spending my own money on supplies, it works out.”

The average starting pay for a Pennsylvania teacher is about $47,800, or the 11th in the nation, according to the National Education Association.

But while the commonwealth is among the higher-paying states, teacher salaries have failed to keep up with the rising costs of a college education, stated the report by Teach Plus Pennsylvania, an organization that seeks to mobilize teachers to get involved in policy discussions. The inflation-adjusted weekly wage for most college graduates has climbed by about 28% since 1996, but teacher pay has remained relatively level, according to the report.

“Overall, the rising cost of college compared with the stagnant wages of teachers leads to an unattractive cost-benefit equation for prospective teachers, particularly for those from low-income backgrounds who must take on significant debt to attend college,” the report states.

A Pennsylvania lawmaker, Rep. Patty Kim, has proposed improving teacher pay in the state by increasing minimum educator salaries from $18,500 to $50,000. The Dauphin County Democrat’s legislative proposal would then raise the annual pay to $60,000 over time.

‘Chipping away at those inspirational things’

Melissa Statman used to show her high school students how to make flash paper that burned in different hues depending on the chemicals they contained. She’d learned by experience that lessons involving fire were always winners with the students — and helped them remember the scientific concepts she was trying to teach them.

She also enjoyed taking them down to pull samples of water from local streams for her science lessons.

But as time went on, Statman felt like the type of teaching she loved was fading away, squeezed out by test preparation.

“They kept chipping away at those inspirational things we could do with students,” she said. “Because it was all about a test score.”

Statman had earned certifications that enabled her to instruct in a wide range of courses, from physics to forensic science. And while she enjoyed bouncing from one subject to another, it was also taxing.

Her job duties multiplied even more after her northwest Pennsylvania school district launched a cyber academy and assigned her to teach math and science for the new program. Statman found she could barely keep up with teaching 12 classes, staying up to speed on numerous different subjects and meeting one-on-one with students.

At one point, she was routinely waking up at 4:30 a.m. to take student attendance because it was her only pocket of free time in the day.

Statman, who suffers from rheumatoid arthritis, said her condition was worsening in a vicious cycle because of her job demands. As her stress shot up, her pain increased, which in turn worsened her insomnia and compounded her anxiety even further.

Advocates have cited isolating and taxing working conditions in schools as a factor driving teachers out of the profession. Though there’s a lack of data on why Pennsylvania educators leave their jobs, researchers have consistently found that low salaries and poor job environments are the primary reasons teachers quit.

Several other states have taken steps to address this by creating new opportunities for career advancement and mentorship and setting aside funding so districts can reward their highest-performing teachers.

In Statman’s case, she was both working as an educator and serving as president of the local teachers’ union to help tackle some of the concerns her Penncrest School District colleagues were raising about their workplace.

But as COVID-19 set in, she watched as turnover on the school board changed the panel’s dynamic.

More: Libraries to locker rooms: How a religious law firm is changing PA school policies

The first year of the pandemic, Statman said union leaders were able to sit down with officials and negotiate an agreement to keep teachers safe. The second year, the board as newly constituted seemed to have little interest in bargaining, she said.

Exasperated, she checked the teachers union website on a whim one day and found a job posting in Maine. In December, she walked away from her roughly 25 years in teaching and started her new job with the Maine Education Association.

“I have a demanding job,” she said of her new union position. “But I still feel like I can breathe now. … And I can sleep.”

‘Bitter icing’

Jake Miller, a former teacher in the Cumberland Valley School District, credits the educators of his childhood with saving his life.

An elementary school teacher helped him get through the year of his parents’ divorce, he remembers. In a school where kids were bullying Miller for his eyeglasses, one teacher introduced him to new friends. A reading specialist figured out that Miller was suffering from dyslexia and taught him to speed-read, despite his learning disability.

In middle and high school, teachers instilled in him a love for math and literature and inspired him to take his studies seriously instead of drinking and doing drugs.

His mother encouraged him to enter the teaching field himself, and as a college student, he decided he’d give it a try.

But Miller’s entry to the profession was no breeze; he has a vivid memory of a placement teacher telling him he wasn’t cut out for the classroom and that he should pursue a career in politics instead.

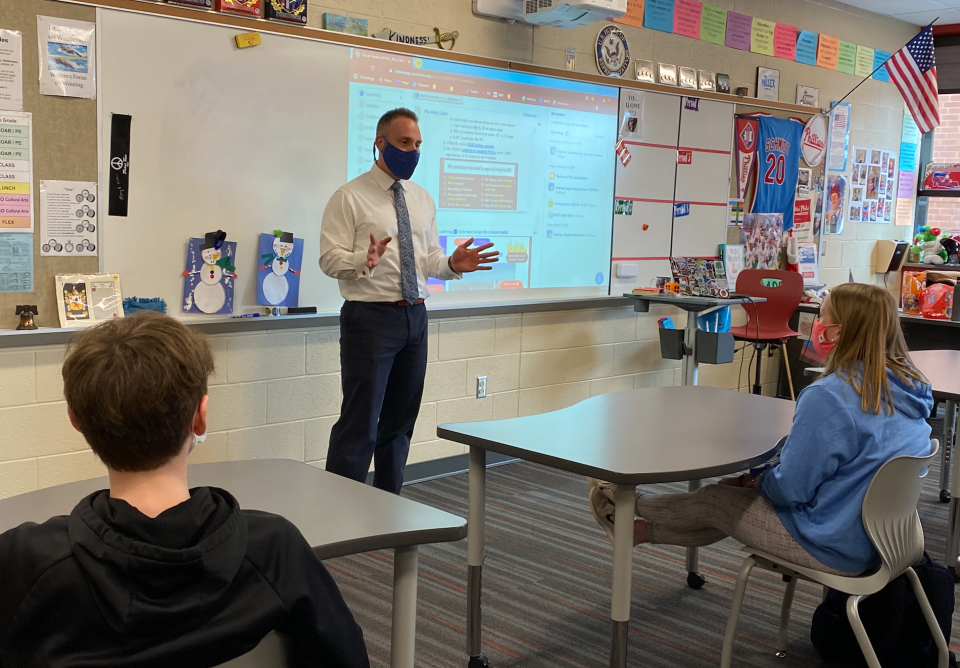

He stuck with it anyway, landing a job at his former high school and later at a Mechanicsburg middle school. And though it was tough at first, he says he eventually began thriving in the profession. Miller, who has taught social studies, English and math, earned statewide recognition in 2016 for his history teaching and was a 2019 semifinalist for Pennsylvania teacher of the year.

As time wore on, though, his job went from demanding to grinding.

Miller struggled to keep his head above water during COVID-19, between the time he had to take off when his own children contracted the illness and having to cover for other teachers who were out sick.

On top of all that, one of Miller’s lessons on the post-Civil War period touched off a firestorm in the community. To help students empathize with people from that era, he created an activity in which students imagined living as a person from that time — and highlighted the many barriers that Black people faced.

Miller said the students seemed to love the exercise. A group of vocal parents, on the other hand, “grabbed their pitchforks” and threatened to sue the district and Miller over the lesson, which they felt contained elements of critical race theory.

“That just felt like very bitter icing on the cake,” Miller said.

So after 16 years in education, he walked away from the profession last year.

Advocates say the wave of political activism that has borne down on school districts over the last several years has at times opened a divide between teachers and some members of their communities. Conservative activists have accused teachers of trying to sexualize kids, inflame racial tensions and indoctrinate children into progressive or Marxist ideologies.

Because of this divisiveness, “it’s going to be harder to attract and retain good teachers and good administrators,” said Sharon Ward, a senior policy adviser for the Education Law Center. “I think, as a result, we’re going to have kids who are really unprepared.”

Since quitting teaching, Miller has become a business consultant, a job that he finds less stressful and that delivered a 50% raise over his teacher salary.

He recently visited a local high school to teach teens about how to prepare their college application, and afterward, one of his former students walked up to give Miller credit for helping him become the man he is today.

“I will never, ever get that type of impact doing business consulting,” Miller said.

Still, he doesn’t regret his decision to leave teaching. His new job is better for his mental health and his finances. He’s no longer making a difference with students in the classroom. But he now ends his work day with “something in the reservoir” for his own kids.

This article originally appeared on Bucks County Courier Times: Pa. is struggling to attract, keep teachers. Here are three examples.