A Striking Photographic Depiction of America's Voting-Rights History

There’s no better time than now to view photographer, author (American Originals is his most recent), and AD contributor William Abranowicz’s latest collection: "This Far and No Further—a Photographic History of Voting Rights." “Photography has played a major role in moving social justice issues to the forefront,” says Abranowicz, whose work was first spurred by a visit to Selma during a single spare hour when in Alabama on a book project. “It blew me away," he recalls. "The walk over the Edmund Pettus Bridge and thoughts of the 1965 marches and beatings really moved me, far beyond what I expected.”

This show—an eerie, contemplative collection of landscapes, faces, and key structures, architecture and objects—debuts October 18 at Cliff Fong’s Gallery Matte Black in West Hollywood and is on display until November 29. But that’s not the end. Abranowicz plans to finish the photography for the project by early 2019, then work on essays and curate original FSA oral histories with former slaves for a book to be published before the 2020 election, reminding Americans how critical their single votes can be. Of his decision to focus on the subject, he says, “Think of the Vietnam War and the whole civil rights era. Images changed the course. Photography has that wonderful power.”

His own reading list grew exponentially with the dive into this subject. John Lewis’s autobiography Walking With the Wind conjured images in his head, and Abranowicz continued poring over everything he could find on the period, especially at local libraries as he traveled the network of infamous Southern landmarks. “There’s a big tourism market in civil rights,” says the lensman, adding, “even the U.S. government has a trail, and the National Park Service has a wonderful body of research and data on important—and often neglected—sites.”

Abranowicz spread his wings from his first Selma experience, journeying to Montgomery and Birmingham, Alabama, and the Mississippi Delta to capture a startling reality. “Montgomery is a sleepy city,” he says—one with several major Confederate monuments, including one at the door of the capitol building that reads “something like, ‘fought to protect the noblest of the races,’” and another in honor of a doctor who performed gynecological experiments on slaves. “A block away is the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Decter Ave. Church,” he points out. “It’s a sleepy place, but one that has this undercurrent of divisiveness.”

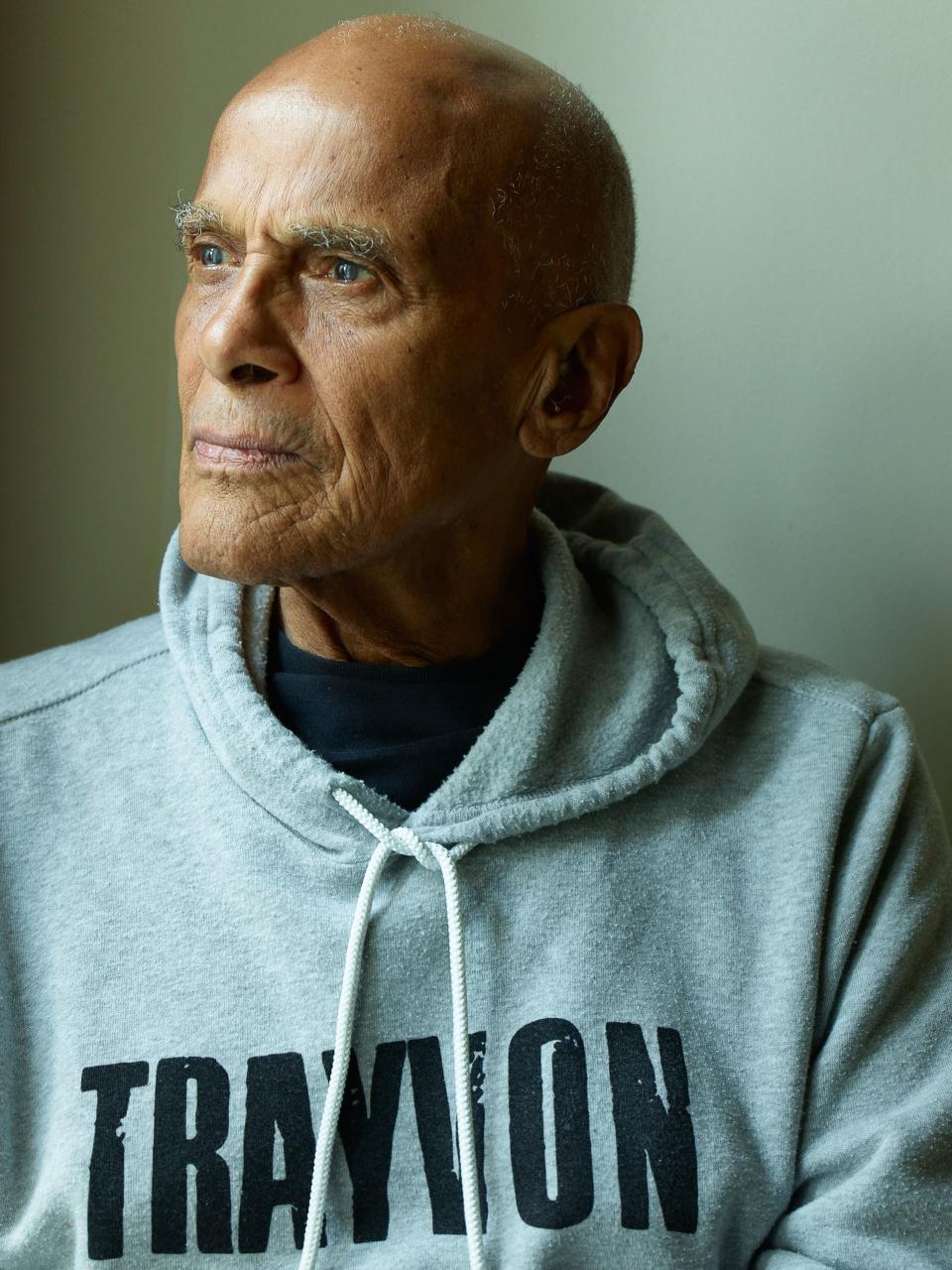

Most symbolic to Abranowicz is an abstract image he made from Commercial Street of the Alabama River, where steamboats brought chained slaves from New Orleans to be marched up to trains—an assembly line of injustice that grew slavery in the state from 40,000 to more than 400,000 in just a couple years. Portraits also figure into the equation. Luck and access played a role in photographing the likes of John Lewis (who he ran into in a hotel lobby in Boston, where Lewis gave the commencement speech at Abranowicz’s daughter’s graduation), a Trayvon Martin sweatshirt–clad Harry Belafonte (through mutual friends), and Sergeant Shriver Poverty Law Center lawyer Kimberly Merchant, whom he sat beside on a plane.

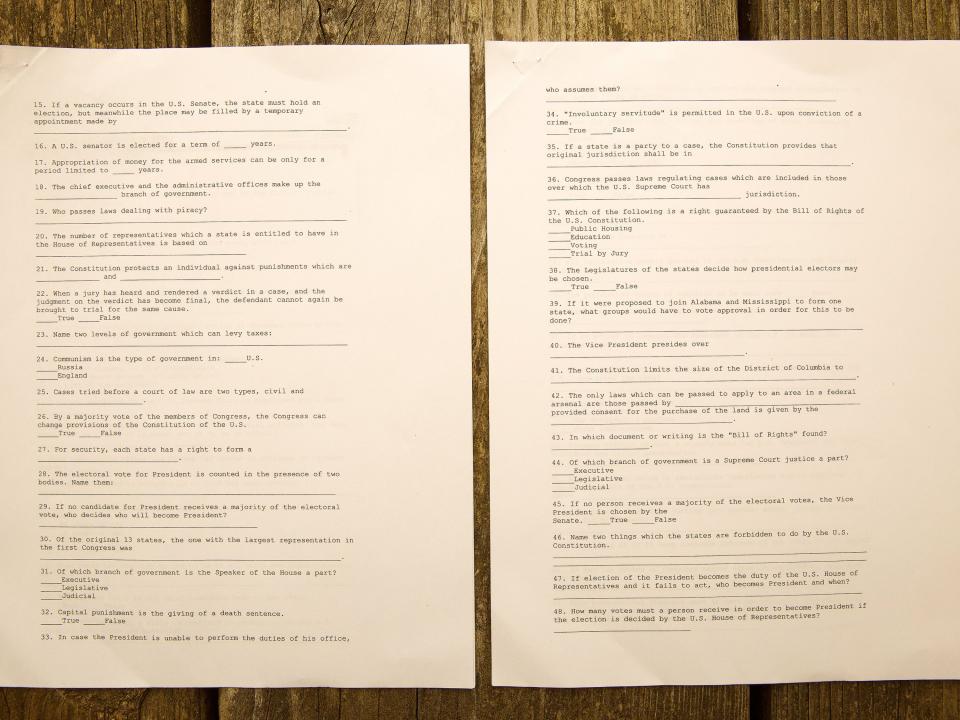

Because of the nature of this multi-pronged history, voting rights naturally spills over into civil rights. To Abranowicz his most searing images are of the trail of Emmett Till and the seed barn where he was tortured, the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the shoes 14-year-old Denise McNair wore when killed at the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, and a copy of the voting registration literacy test. In a political climate that could hardly get more contentious, tragically, these artifacts and events have never been more relevant. Ultimately Abranowicz put this frighteningly honest collage together to “see if I can get people to feel what I do in these places, and to understand what it took to procure the vote for this movement.” And, he adds, “now how failing it is that 50-plus years later, voting suppression efforts are underway in 24 states, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. It’s a dark topic, but Leonard Cohen and Remi both talk about wounds letting the light in.”

RELATED: Step Inside the New National Memorial for Peace and Justice