LAPD officers are firing bullets and 'less lethal' rounds at same time, with deadly results

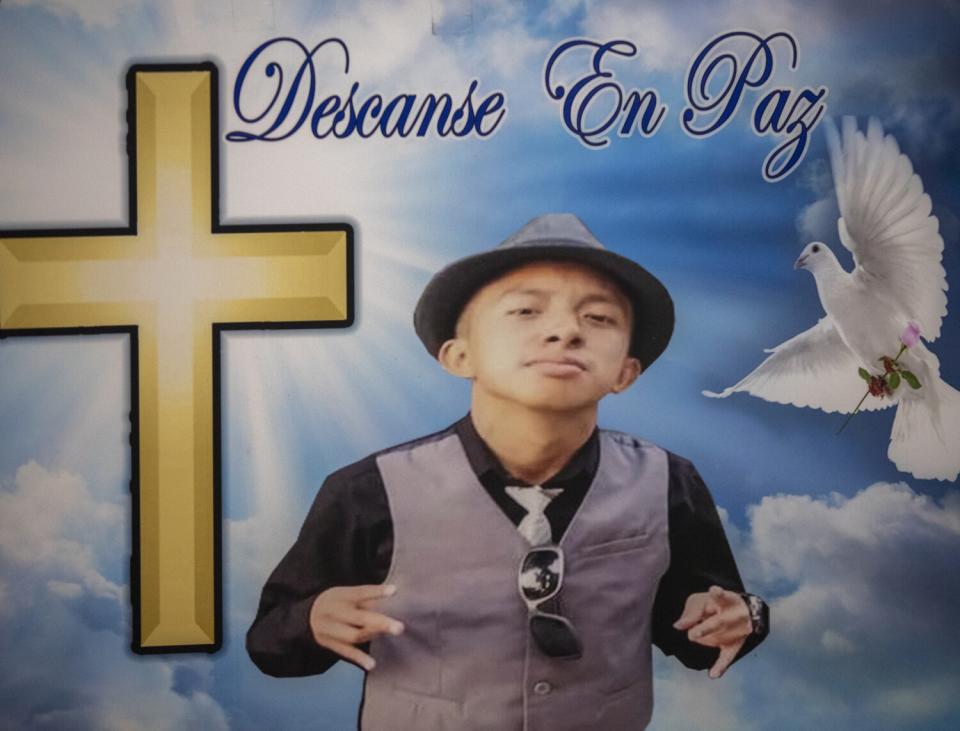

Margarito Lopez Jr. had been threatening suicide with a butcher knife to his neck for nearly 10 minutes when he suddenly stood and took a few steps toward the line of Los Angeles police officers in front of him.

The officers had been trying to calm the troubled man in bursts of English and Spanish, according to police video from the encounter. They kept their distance while trying to talk Lopez out of harming himself. They lined up behind a barrier they'd created with their patrol cars. And they brought out a projectile launcher as a "less lethal" option in the event they needed to use force.

Lopez stood on the sidewalk and slowly began to turn away. Then the officers opened fire with the projectile weapon — and their handguns. He crumpled to the ground, dead at 22.

The officers' decision shocked Lopez’s sister and others watching on the street.

"They could have done so many other things," Sonia Lopez said in a recent interview with The Times. "They didn’t even try to see if something else would work."

Lopez's shooting outside a South Central apartment building in December is one of at least eight in the past two years in which groups of officers simultaneously fired handguns and weapons meant to avoid killing, such as projectile launchers or Tasers, according to a Times review of nearly 50 LAPD shootings since the start of 2020 along with hours of associated police video.

The approach gave the "less lethal" options little or no time to work and resulted in five deaths.

The shootings often came in sudden bursts after longer standoffs, when officers had readied themselves with alternative weapons but failed to prioritize their use before resorting to deadlier force.

Some suspects were shot at a distance from police, including one man with a sword who was simultaneously shot in the street with a projectile and a rifle round from 77 feet away. Others were hit at close range, including a man who was simultaneously shot and Tasered next to his mother in a narrow hallway.

In all eight shootings identified by The Times, the suspect was armed with a knife, blade or blunt object, never a firearm, making them part of a broader increase in LAPD shootings of people without guns. The trend has raised alarms within the LAPD, and top commanders have promised to revisit training to better teach officers to slow down and let Tasers and projectiles take effect if possible before firing live rounds.

The trend also has infuriated the families of those shot and other police reform advocates, who say the incidents show not only a critical breakdown in police training, but also a lack of concern among officers for the people — many of them mentally ill — they end up shooting.

"The LAPD manual says there must be reverence for human life," said Luis Carrillo, the Lopez family's attorney. "They do the opposite of having reverence for human life. It’s like a knee-jerk reaction where they just go from 0 to 100."

Lopez's shooting followed two similar incidents in which officers fired live and less-lethal rounds at men armed with knives who appeared to be in some sort of crisis.

In early October, officers shot a mentally ill man named Grisha Alaverdyan simultaneously with live and beanbag rounds after they confronted him on the busy tourist corridor and he took a step toward them with a knife.

Alaverdyan was a suspect in a Hollywood Boulevard stabbing. Once wounded, he turned and ran a short distance from the officers before lying on the ground. He was charged with assault with a deadly weapon, found incompetent to stand trial in mental health court and ordered to receive treatment.

Later that month, officers fatally shot Melkon Michaelidis as he moved toward them with a knife in the middle of a Valley Glen street. The officers had been trying to get Michaelidis to drop the blade for more than six minutes, standing in a line across the street with various weapons drawn — including a beanbag shotgun and a Taser.

"Talk to us," said the officer with the beanbag weapon.

"God's on your side man, just put the knife down," said the officer with the Taser.

Video then showed Michaelidis advance as the officers screamed at him to back up. Then they opened fire simultaneously with beanbag and live rounds.

"Oh, no!" screamed the officer with the Taser — who had yet to fire.

Julie Navasardyan watched it all happen from the Glam Laser & Beauty Studio across the street, where she's worked for two years. She said a crowd had gathered, including people who appeared to be Michaelidis' family and were comforting one another with the fact that the officers had less-lethal weapons drawn that were designed to control, not kill.

The officers "shouldn’t have done what they did," she said. "I just feel bad for the family. They didn’t expect the cops to kill him. They just thought they were going to restrain him."

Most recently, on April 6, officers responded to a report of a man threatening people with a knife in Panorama City. When the suspect, Jesus Castellanos, allegedly began walking toward the officers with the knife, they opened fire simultaneously with a Taser and handgun, police said. He died in a driveway.

Video from that incident has not yet been released.

LAPD shootings of people with knives or other edged weapons have been on the rise for the last two years. They represented 19% of all shootings in 2019, 23% of shootings in 2020 and 38% of shootings in 2021 — a year that ended with officers opening fire 37 times, killing 18 people. That compares with 27 shootings with seven fatalities in 2020.

Among the suspects in the 37 shootings last year, 17 were experiencing a mental health crisis, according to the LAPD. That marked a huge increase over 2020 in shootings driven entirely by incidents in which the suspects had edged or blunt weapons, not firearms. More than a quarter of the suspects were homeless.

In January, LAPD Chief Michel Moore acknowledged that the volume of 2021 shootings was a change in the wrong direction for a department that has seen steep declines in police shootings for decades. And he told the civilian Police Commission that he was ordering a "deep dive" audit of the department's training on the use of deadly force as a result.

Moore said the review would specifically examine whether officers are giving less-lethal weapons enough time to stop people before resorting to firing live rounds — particularly in instances in which suspects do not have firearms. It would also consider whether officers were "accurately interpreting" whether they were in "imminent peril" before opening fire, he said.

Moore and other LAPD commanders were back before the Police Commission Tuesday, presenting their annual use of force report for 2021, which the commission will revisit for a deeper discussion in May.

The issue of better training on the use of less-lethal weapons as an alternative to deadlier force came up again, with Moore and Assistant Chief Dominic Choi assuring the commissioners that they take the issue seriously and are revising training.

Choi said the department had recently developed a training aimed at reducing deadly police shootings by "enhancing command and control efforts and accountability and really letting less-lethal options work before escalating the incident."

The new "Critical Thinking and Force Mitigation" course teaches officers how to have a conversation with suspects rather than just screaming orders at them, Choi said. It also highlights the importance of officers using space and time to prevent confrontations; the tenets of "fair and unbiased policing;" the department's requirement that officers render aid to suspects they have shot; and the availability of other resources to help deal with mentally ill suspects, such as the department's Mental Evaluation Unit, Choi said.

Commission President William Briggs, who along with other commissioners has previously raised concerns about the rise in shootings of people with knives, said they want to see "more de-escalation and use of non-lethal force" — and more training on both.

"I firmly believe we need to better train our officers around this issue, and this is one of the reasons why we as a commission have requested an increase in the department's budget to better train our offices for these types of situations as well as others," Briggs said.

Sonia Lopez wishes the officers who shot her brother had been better trained — or just more compassionate.

Margarito, the youngest of 10 siblings, stood less than 5 feet tall, and he looked much younger than his 22 years. He'd grown up in a two-story home along East Adams Boulevard, and often sat on the front steps where he'd dance to music and dream of being a famous singer.

How the skinny young man could have represented enough of a threat to a team of officers for them to fatally shoot him does not make sense to her, she said.

"There were so many of them, and not one of them thought of using a Taser?" Sonia said. "They should have thought. Maybe he’d still be alive."

Instead, neighbors and friends have turned the spot where Lopez was shot into a memorial, even though he was buried in the family's native Guatemala.

Every day, his sister said, people come and leave candles.

"This is his cemetery," she said, "here in front of the house."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.