Struggle to survive: Monarch population at all-time low, new report says

Natural landscapes, once vibrant with a diverse array of native grasses and wildflowers, now stand barren — replaced by freshly plowed soil and scraps of litter scattered by the wind. Backyard gardens, once adorned with the blooms of various flora, have succumbed to the dominance of bright green Bermuda strands. And extensive stretches of milkweed have either fallen victim to herbicides or instead become asphalt landscapes and residential communities.

In a foreseeable outcome of these events, experts said one major consequence was always certain: Monarch butterflies would disappear.

For decades, scientists have alerted the public of this probable scenario, so it is unsurprising that the National Commission of Protected Natural Areas in Mexico — where the species' eastern population migrates for winter — announced earlier this week the species' lowest population on record. Diminishing to 0.9 hectares (approximately 2.22 acres) of overwintering area — the most reliable metric used to estimate sustainable populations — that number was more than double at 2.21 hectares (approximately 5.46 acres) just last year, according to the report.

At the same time, the western counterpart of the species in California has also experienced a notable decline over the last two winters. Earlier this week, the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation revealed results from the organization's annual Western Monarch Count, in which scientists and volunteers track butterfly populations across 256 overwintering sites. In total, they counted 233,394 butterflies — down nearly 30% from last winter's count of more than 330,000.

As some experts theorize, both populations are, perhaps, overwintering in new locations as they adapt to climate change — seemingly disappearing to the human eye. Or, alternatively, the entire species actually is dying off en masse, as many more believe. Regardless of which scenario is more accurate, either should serve as a telltale sign to the regions they've long inhabited.

"Failing to protect one of the most iconic insect species in the U.S. suggests we are not capable of managing sustainable systems for both conservation and human uses," said Scott Longing, associate professor in the department of plant and soil sciences at Texas Tech University. "By ensuring its habitat is protected and nutritional resources are available, other wildlife should benefit."

More: California's monarch butterfly numbers drop; experts say storms may be to blame

Where did all the butterflies go?

Known for their incredible migration, trekking more than 2,200 miles from Canada to Mexico twice a year, the monarch butterfly is one of the most recognizable species in the nation. Often at the forefront of environmental campaigns, the species has long served as a beacon for wildlife conservation.

In the years leading up to their rapid decline in the 1990s, observers along their migratory routes could witness the remarkable sight of dozens to hundreds of bright orange monarch butterflies gracefully fluttering through the area on any given early spring or fall day. Now, spotting a hundred of them gathered in a single area would be almost unimaginable unless the space was specifically managed or designed to attract this species.

But even then, it's a gamble.

Despite creating a habitat for native species in her backyard, Tierra Curry mentioned that she only saw three monarch butterflies throughout the entire summer at her home in Kentucky — a notable decline from years prior.

"I know that the previous summers I've had dozens and dozens," said Curry, who is a senior scientist for the Center for Biological Diversity. "I've got four plants of milkweed, and I converted my lawn to native habitat and to only see three all summer — that was just bad."

Currently, the species is still awaiting a decision from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for its listing under the Endangered Species Act, which the agency will determine this year, though the International Union for Conservation of Nature listed the species in 2022. The latter, at the time of its decision, estimated a decline of 99.9% for the western population since the 1980s and 84% for the larger eastern population since the mid-1990s.

It's impossible to attribute the blame on one single cause: Cropland conversion, herbicides, automobiles and development have all undeniably impacted the eastern population, while the western population is dwindling due, in part, to such reasons as logging, deforestation and wildfires. And adding another layer to the multifaceted factors affecting the species, in the most recent decline of the western population, the Xerces Society also attributed harsh winter storms.

"(These storms) meant we entered the spring breeding season with fewer butterflies and saw lower numbers this summer," said Emma Pelton, a monarch conservation biologist for Xerces Society, in a news release. "So, it is not surprising that the overwintering population is down."

Numerous expert organizations, including Xerces Society and the Natural Resources Defense Council, have asserted that the initial decline of the eastern population of monarch butterflies — those familiar in the Midwest and South — are intertwined with the widespread adoption of genetically modified crops resistant to glyphosate. According to the National Pesticide Information Center, glyphosate is a non-selective herbicide, meaning it will kill most plants.

This new resistance meant that crops were now protected from herbicides, while effectively removing weeds perceived as agricultural pests. But this implementation came at a cost, culminating in the near-total elimination of milkweed — the species' primary host plant — from agricultural fields throughout the Midwest, a region crucial for the annual migration and overall population of the monarch butterfly.

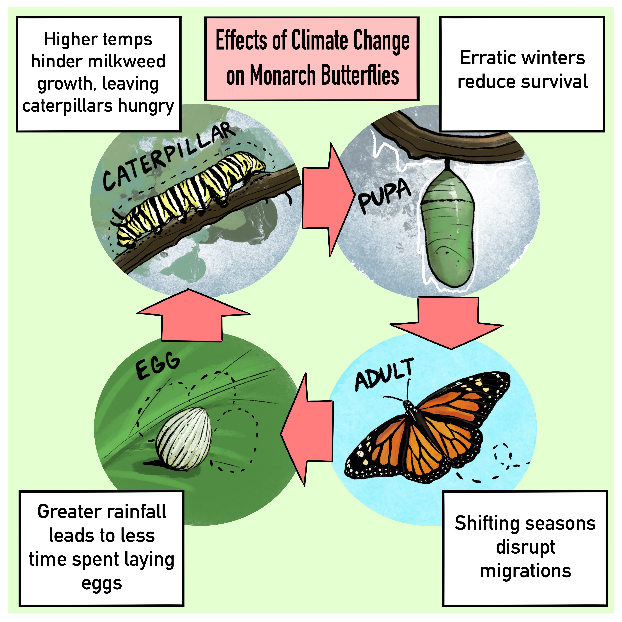

Amplifying the initial challenges, Curry said the climate crisis is exacerbating issues even further throughout every stage of the monarch butterfly's life cycle.

"One important thing about the monarch is, there are scientists who do their counting in the summer, and they say monarchs aren't declining because of their summer count," Curry said. "But the monarchs have to survive the migration in the winter. So, it doesn't matter that there are monarchs and protected areas in the summer if we don't have big enough numbers to survive all of the migratory chaos now."

As displayed in an illustration by the U.S. Geological Survey, in wetter conditions, butterflies lay fewer eggs, while warmer temperatures hinder the growth of milkweed is hindered by warmer temperatures, depriving caterpillars of adequate forage. At the same time, unpredictable winters can freeze overwintering pupae, while shifting seasons can disrupt the butterflies' natural migration pattern.

Moreover, the increasing temperatures have shortened the duration of their diapause — a period of suspended development for insects and other invertebrates, akin to brumation in reptiles and hibernation in mammals, that allows them to conserve energy in unfavorable weather conditions. According to Curry, this change has prompted earlier northward migration over the last few years, and upon reaching the U.S., the milkweed has not yet bloomed, leaving them with minimal to no forage in their travel.

And in a notable development last year, wildfires set ablaze their overwintering grounds in the forests of Central Mexico, Curry added.

"Climate change could undermine the entire migration," she said, noting that it's already eroded a decade's worth of species recovery efforts and hundreds of millions of dollars.

Recovering the species

Despite varying perspectives on the most significant challenges that the monarch butterfly is hoped to overcome, experts universally agree on the importance of ensuring the survival of the species.

The monarch butterfly, functioning as an indicator species, acts as a barometer for the well-being of a local ecosystem through its presence. A higher abundance of monarch butterflies in an area implies a more sustainable environment. Conversely, areas with a scarcity of monarch butterflies may be less environmentally sustainable.

But beyond their role in the natural world — from pollinating hundreds of plant species to serving as food for migratory birds — Curry emphasized the cultural significance of the species.

Native communities in Mexico, for instance, frequently link butterflies with the Day of the Dead, as their arrival consistently coincides with this annual event. For many, monarch butterflies symbolize the souls of departed loved ones returning from the spiritual afterlife to join their family's earthly celebration.

"They're so familiar, and so many people love them. There's such a huge cultural significance in Canada, the U.S. and Mexico," Curry said. "But beyond that, because they were so numerous, they played a lot of different roles in the ecosystem."

Around a decade ago, the majority of species survival plans emphasized the restoration of milkweed plants, which serve as the host for monarch butterfly larvae. The plant contains a toxin that fortifies their system from caterpillar to butterfly, offering protection against predators; it also serves as a primary food source for the species.

Based in the South Plains of Texas, Longing highlighted the particular importance of milkweed availability in the state. Given the current climate conditions, with prolonged periods of drought, the absence of the plant has become evident in monarch populations, he said.

"Texas is central to conservation in the U.S. because it is the gateway to the entire migration corridor of the eastern population of the monarch," he said. "Climate conditions in Texas that promote diverse vegetation and nutritional resources influence the first generation of monarchs that head northerly out of Mexico.

"When conditions are most unfavorable, monarchs probably don’t acquire the requisite resources needed to sustain populations," Longing added.

In a 2016 study published by the Royal Entomological Society, researchers claimed that to increase the monarch support capacity to 3.2 overwintering hectares (7.9 acres), a total of 425 million milkweeds would need to be added. For a proposed conservation goal of 6 overwintering hectares (14.8 acres), the study suggested that 1.6 billion plants would be required.

To provide a sense of scale, the land area needed for milkweed to meet the conservation goal is approximately 92,000 acres — roughly 5,000 acres larger than the city of Lubbock and equivalent to the size of three Palo Duro Canyons. Additionally, if all the plants were stacked together, their height would be long enough to wrap the earth 49 times.

Still, that is, if the populations existed in a stable climate with lower temperatures and fewer climate disasters.

Already, various state and federal agencies and organizations have invested hundreds of millions of dollars into milkweed restoration to support summer populations. But this effort has swiftly proven futile in the face of the impacts of climate change.

"That's why it hit me so hard," Curry said, noting that she was in tears upon learning the data from this week's reports. "No matter how big we get the summer population, they have to survive the winter."

Reporter's Note: The Lubbock Avalanche-Journal translated the names of the agencies in Mexico to English. The official names of the organizations are "La Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales" and "Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas."

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Monarch butterfly population at all-time low, new report says