Stuck in the muck: Will Wilmington's west bank ever be developed?

Editor's note: This article has been updated to clarify that current New Hanover County zoning regulations allow for development on the west bank.

The Left Bank of the Seine in Paris it isn’t.

But there’s still something alluring about the west bank of the Cape Fear River as it streams through downtown Wilmington.

For some, it’s the lack of buildings and the embrace of nature so close to an urban area.

For others, the lure of empty riverfront land across from a thriving downtown is a missed opportunity, an eyesore waiting for a solution. If Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, S.C., can develop their other riverfronts, why can’t Wilmington?

Developers for decades have toyed with the idea of building on the limited high ground amid the soggy marshes and forests of Eagles Island and Point Peter dotted between the remains of the area’s maritime past.

But a lack of infrastructure, along with concerns about the viability of any major developments among the sensitive environmental wetlands, doomed those earlier plans.

Interest in the future of the west bank was rekindled two years ago when developers floated proposals to build a pair of high-density projects along the riverfront. Those plans prompted a conservation group to launch an effort to raise $16 million to purchase and conserve the land, an effort that ultimately failed.

But the building plans also stalled, stuck in the muck over just what officials and the community really want for the largely undeveloped land that’s a historical tapestry of Wilmington’s past.

That’s a question New Hanover County officials are now trying to answer.

A history of agricultural uses

When colonial residents of Brunswick Town in the early 1700s decided to move farther up the Cape Fear and make Wilmington the state's major coastal hub, they chose the river’s east bank because it offered higher, more solid ground to develop and build on than marshy Eagles Island. Its high bluffs also offered easy access to fresh water and more security.

For decades, the left bank was largely left undeveloped aside from some agricultural uses. But as North Carolina became central to the British naval stores industry, mills and shipyards to meet the burgeoning business began to proliferate along the left bank. This industrialization continued during the Civil War and into the early part of the 20th century.

But as the needs of the shipbuilding industry grew in size, the industry migrated back across the river, leaving the left bank largely a cemetery of abandoned warehouses, boatyards and vessels.

A century later, remnants of the riverbank’s past industrial history dot the shoreline amid the hulking presence of the 35,000-ton Battleship North Carolina. A few maritime businesses also hug the river between Point Peter and the Isabel Holmes Bridge.

TIDAL WOES: Why officials are betting on wetlands to keep the Battleship North Carolina afloat

Obstacles to development

While developers have hungrily eyed the prime riverfront location within shouting distance of booming downtown Wilmington for decades, a number of obstacles – political and practical – have kept development of the river’s west bank at bay.

With much of the land across the river being too wet for development, any future building would have to be centered along the Cape Fear. A handful of private parcels line the waterfront, both north and south of the battleship. Based on current zoning classifications, although it could be economically challenging, developers can build on those lands if they so choose right now without needing special permission from the county.

Because the available land for development is so small, any projects would likely have to be high-density and potentially tall to make them financially viable. A proposal in the early 2000s to build a pair of 20-story towers next to the battleship, however, generated howls of protests from residents of Wilmington’s Historic District worried over what impacts the project would have on, among other things, their viewscape.

A more practical issue is the lack of infrastructure, namely water and sewer, on the west bank to support any intensive development. While a small water line that runs under the river does supply the battleship, it wouldn’t have the capacity to support other projects. Extending lines that already comes down U.S. 421 south of the Isabel Holmes Bridge would be a very expensive and challenging project.

Other issues include traffic access, emergency response, zoning questions, and just what sort of development – if any – county officials and the public would like to see across from downtown.

Local politics also have gotten immersed in the discussions, with developers threatening to seek voluntary annexation by Leland or Wilmington.

Q&A: As Cape Fear River west bank developers eye Leland, here's how annexation would work

Deciding what should be allowed

Rebekah Roth, New Hanover County’s planning director, said the developable land on the west bank is zoned a mix of commercial, industrial and mixed-use and is inline with the county’s comprehensive plan, adopted in the early 2000s, to allow development in the area.

Now, county officials are looking to refine the parameters of what type of projects should be allowed to mitigate risk and take environmental considerations, including major flooding concerns, into account. Some property owners on the west bank have said they are waiting to see the new regulations before moving forward with their development plans.

County officials say it’s a fine line they are looking to walk.

“I know that these private property owners have a right to do what they want to do with their property, but they don’t know what they can do …” said Commissioner LeAnne Pierce.

MULLING IT OVER: Months after first proposal, plans for Wilmington west bank hotel, spa still under review

Proposals on deck

One of the large projects floated for the west bank is a 290-unit hotel and spa by developer Bobby Ginn, which would be built next to the battleship and across the river from the foot of Market Street.

New Hanover County property records show that Wilmington Resort and Club, LLC, registered to Bobby Ginn, purchased almost 19 acres at 105 and 125 Battleship Road Northeast for $8 million last October.

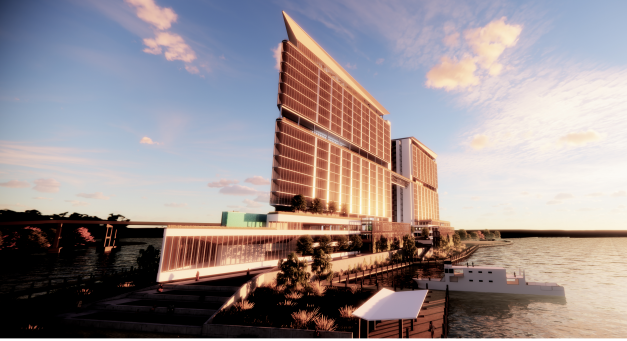

The other major project would be built roughly a half-mile north on 8.2 acres at Point Peter, where the Cape Fear and Northeast Cape Fear rivers meet. KFJ Development initially proposed an ambitious $500 million proposal for three skyscrapers that would include 300 apartments, 550 condominiums, a hotel and commercial areas.

While any future project will likely be scaled down, KFJ’s Kirk Pugh said he still hopes to find a middle ground with county officials that would allow “Battleship Point” to move forward.

“Our project is still very much alive, but our plans are somewhat dependent on what the county ends up doing with the zoning ordinance,” he said. “Depending on what they create and what options we have, and what options we have for a variance if needed, that’ll determine what our final plans end up looking like.

“As far as I’m concerned, we’re still moving forward with it. It’s just a matter of trying to get some traction and figure out what we’re going to be able to build.”

STALLED OR JUST PAUSED? After months of quiet, what's next for Wilmington's west bank?

The role of climate change

A coalition of environmentalists, researchers and historical preservationists say they already know what should be done on the west bank – little to nothing.

With climate change forecast to raise water levels by up to 3 feet in places by the latter half of this century, they say allowing development in a low-lying area that’s already prone to flooding is short-sighted.

A recent study commissioned by the battleship, which has launched an ambitious project to help mitigate chronic flooding that often leaves the attraction marooned, showed a more than 7,000% increase in tidal flooding since the historic vessel came to Wilmington in 1961. Between just 2011 and 2020, there was an eyewatering 770% increase in flooding events − a figure that's likely increased since then as researchers document sea-level rise increasing.

Adding to the concern, Wilmington’s official tide gauge at the base of the Cape Fear Memorial Bridge, which has been measuring water levels since 1908, recorded its highest reading ever in August 2020 when Hurricane Isaias skirted the region just offshore.

DEEP DIVE: Developers want to build on Wilmington's west bank. Is that even feasible?

Climate change is expected to fuel the formation of bigger and more powerful hurricanes and more intense rainfall in inland areas, events that could mean more runoff cascading into the Cape Fear River and increasing the potential for flooding.

Other concerns include increased stormwater runoff that could impact nearby wetlands and areas like the battleship and development damaging or burying cultural resources, including remnants of the historical Gullah Geechee presence on Eagles Island.

Developers have said projects can be designed to handle flooding concerns, such as having parking decks as their lower levels to reduce the amount of impervious surface versus surface parking and to keep people out of harms way, and existing regulations require the protection of cultural resources and stormwater impacts on neighboring properties to be taken into account.

But Kemp Burdette, the Cape Fear riverkeeper with the environmental advocacy organization Cape Fear River Watch, said it's not worth the risk when we know what's coming.

“That area is just not suitable for any kind of intense development," he said. "It just doesn’t make any sense to build structures that people are going to live in in a place that you can’t access during King Tide or even many regular high tide events.

"I think we need to find another solution that helps all parties and protects the public, and I think we can do that."

Reporter Gareth McGrath can be reached at GMcGrath@Gannett.com or @GarethMcGrathSN on X/Twitter. This story was produced with financial support from the Green South Foundation and the Prentice Foundation. The USA TODAY Network maintains full editorial control of the work.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Will Wilmington, NC's west bank ever be developed?