What are students learning about climate change in Georgia? And why? It’s complicated

Today’s eighth-grade class was born around 2010, the start of the first “hottest decade on record.”

And this year has been the hottest year ever, according to scientists.

Just before this year’s winter break, the students in a physics class at Dalton Junior High School in Northwest Georgia learned about waves and albedo from teacher Sarah Ott. The lesson is about the phenomenon of the percentage of reflected versus absorbed light.

“Why will the lack of polar ice caps increase temperatures?” she asks in the assignment. The students conducted an experiment to learn that the darker color absorbs more heat and thus more ice will melt. The lesson ends.

Although the albedo phenomenon is important to understand, so is the current climate change phenomenon, experts argue.

Yet, there is no requirement for Georgia teachers to teach that human activity is responsible for the current crisis, the severity of the current changes, and future predictions, nor how to mitigate and adapt with solutions, according to current Georgia state standards.

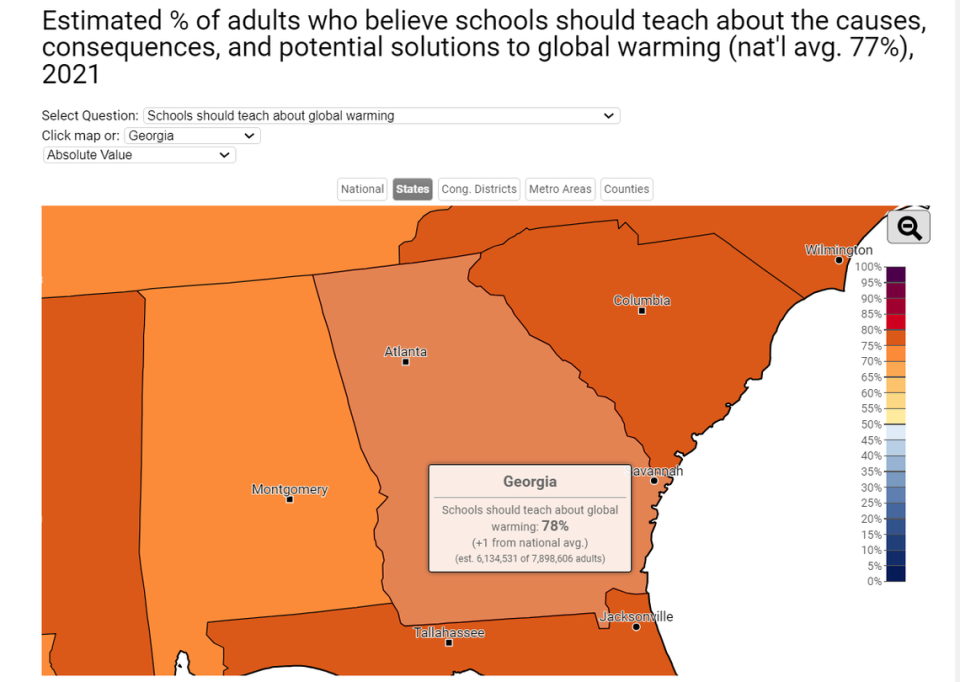

Despite this, 78% of Georgia adults believe schools should be teach about the causes, consequences, and potential solutions to global warming, according to a 2021 poll by Yale Climate Change Communication.

Georgia is a barrier island state, with nine barrier islands.

“Coastal resilience, sea level rise, and other elements of climate change directly impact the entire state in many ways, there is an economic impact to all of this,” Amanda Townley executive director of the National Center for Science Education (NCSE) said. “There are many different climate issues and it’s most unfortunate that we are not doing better in our climate change education. The exclusion of climate education from standards is truly terrifying.”

Standards Open to Interpretation, whose accountable?

In 2020, the NCSE and the Texas Freedom Network Fund vetted all 50 states’ standards to determine whether middle school and high school state science standards address climate change concerning these four key points: it’s real, it’s us, it’s bad, & there’s hope/solutions.

Georgia was one of six states that earned an F from the review scorecard.

“Georgia focuses a lot on natural cycles in its standards,” said Casey Williams, an environmental psychologist from Kansas University, and one of the reviewers from the study. “Natural cycles are a part of climate change, but without the context of the last 200 years of the Industrial Revolution contributing to rising CO2 emissions and what that’s doing to our climate then it loses some perspective.”

The global average atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide has risen from about 380 parts-per-million (ppm) to 423 ppm in Gen Alpha’s short 13 years on this planet, according to observations from the Mauna Loa Observatory.

Any state that scored a B+ adopted the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). Williams said the NGSS is based on the National Research Council’s recommendations, calling it, “one of the biggest overhauls for science education in the last 20 years.”

The Georgia Department of Education (GaDOE) told the Ledger-Enquirer that the state standards are “Georgia owned and Georgia developed” which go through a lengthy approval process, and do not incorporate the NGSS standards.

The Muscogee County School District uses the state’s standards, a district spokesperson said.

The current Science Standards of Excellence in Georgia were last updated in 2019, except for some subjects remaining unchanged since 2016, including environmental science, biology, and earth systems high school courses.

One environmental science standard, SEV2, states, “Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to construct explanations of stability and change in Earth’s ecosystems. Analyze and interpret data related to short-term and long-term natural cyclic fluctuations associated with climate change…”

Townley said SEV2 is the only mention of climate in all of the environmental science standards, and laments that the standard does not go far enough. She went on to add biology is missing climate change from its standards.

“Georgia has no mention of climate change anywhere in biology, even though it largely impacts so many different parts of biology,” Townley said.

There is a “clarification statement” below SEV2 that states, “Short-term examples include but are not limited to El Niño and volcanism. Long-term examples include but are not limited to variations in Earth’s orbit such as Milankovitch cycles.”

The examples in the clarification statement are natural sources, and not referencing anthropogenic sources, a GaDOE spokesperson said, adding that teachers are not limited to only these examples but can choose to cover additional examples.

Townley points out the variance in district-level teaching is problematic, calling it the “baseline” for what is taught in a classroom. Districts may add to the existing curriculum but not amend it.

The good and bad of teacher autonomy

Sarah Ott, the physical science teacher in Dalton, believed climate change to be ‘a hoax’ up until about 2016. She broadcasted her reckoning with the denialism movement in a recent BBC article. Once an avid Rush Limbaugh listener, she heard a National Public Radio story about “Climategate” and realized none of the hoax claims lined up with the science.

Now, she advocates for climate literacy and acts as a teaching ambassador for the NCES, according to Townley.

“Climate change isn’t necessarily one of my standards, but it’s a real-world connection to what we’re learning in class that helps them understand things on a smaller scale,” she said. “I do talk about climate change. I bring it up. I don’t go into it as much with as much detail as I used to be able to because of the way we changed our schedule and it’s just a matter of time.”

As far as teaching it, she has her own climate anxieties, doesn’t want to overwhelm students, and hopes they can get into more details next year.

“I think they will probably get more of the climate change discussion in ninth grade,” she said.

Ott reviewed the environmental standards with the L-E.

“If I am, my old climate denier self and I’m looking at the environmental science standards, I see a way to spin it in a way I want to spin it,” she said.

Ott, like Townley, points to SEV2, and suggests the clarification statement needs expansion.

“A clarification statement should say short-term [climate] examples would include El Nino volcanism Milankovitch Cycles, but it would probably be best if there was another sentence here that said something about how these are non-anthropogenic sources. I don’t see anything in here about [human impact],” Ott said.

It is left to the teachers’ discretion and the student’s curiosity to create any discourse in public schools in the state of Georgia, unless otherwise detailed in the district’s standards.

“There’s a juxtaposition between telling students that this is an issue and it’s a problem we have to solve versus analyzing and interpreting data and letting the students or the teachers kind of decide for themselves whether or not they think this is a problem,” Williams, the Kansas University professor, said.

Williams’s dissertation largely focused on the amount of experience teachers have with teaching climate change.

“They don’t have much training in climate science, and most teachers are not aware of how to address the issue in the classroom,” Williams said. “So if the curricula are more open-ended, it can lead teachers and students down a road that can further contribute to confusion and misconceptions.”

A lot of science classes are electives--climate change is interdisciplinary

Some of the science classes that may offer an opportunity to cover climate change are electives, and not required, so many students aren’t getting the coverage they need.

“Climate change isn’t even talked about unless it’s in an Earth Systems or environmental science classroom and those are usually just electives,” Williams explained.

These concepts ought to be brought up across the board, Townley argued. “We need climate literacy standards in social studies, ideally there is interdisciplinary coverage with a lot more than just one substandard.”

Atmospheric science professor at the University of Georgia Marshall Shepherd has been an advocate to reshape what geography is to the public.

In a recent article, “Climate Change Science is Geography: Why it Must be Taught at the K-12 Level”, published in The Geography Teacher, Shepherd said climate change must be highlighted at the K-12 level.

“Geography is by nature a very interdisciplinary field and academic area that encompasses physical science, climatology, and human geography, which has implications on culture and society,” he said. “What better way to tell those stories within the lens of climate change?”

Right now there are elective geography courses offered in high school taught in social studies classes. Shepherd shares the notion with Williams and Townley of climate change science being introduced in middle school, early and often.

“There are probably students who never hear anything about climate change.

The only measure that holds students and teachers accountable is the Georgia Milestone test. In the 8th grade class of 2023, almost half of the 8th grade students scored in the “beginning learner” range at 47%. For Muscogee County, the percentage of beginning learners was even greater at 63%.

Climate Comprehension on the rise at CSU

Interestingly, one environmental science professor’s test at Columbus State University (CSU) suggested that students are becoming increasingly climate literate with respect to NCSE climate standards.

Since 2015, Professor Troy Keller, who teaches Environmental Sustainability at CSU has handed out a “pre-test” on the first day of class to assess where students are when they start his class.

His students can range from freshmen to seniors and most are non-science majors. , though the majority are freshmen or sophomores. The class covers the required science lab credit. Keller said most of the students are non-science majors. The classes range from 125-225 students per semester.

The 10-question test has four that are directly related to climate change competency and understanding: it’s real, it’s us, and here are the solutions.

In the spring of 2016, the average score was 42%.

This year the average score is 74%.

“There has been a significant improvement, from increased awareness,” Keller said. “If we assume the mix of student demographics is the same and we are roughly sampling the same group, that is a pretty startling change.”

His questions are about topics like greenhouse gas emissions, sustainable individual behavior, and climate change mitigation.

“I need to know if they understand what drives climate change,” Keller said.

”

As far as the fourth pillar that NCSE uses in their state grading rubric; “there’s hope”, Keller said students do come to him looking for this.

“They express concern, anxiety about what’s happening,” he said. “I’m not a counselor, but I am an optimist. I don’t want to be Pollyanna about it either. Another big piece of this is climate change is not in a silo. It’s a biological issue, a social issue, a business issue, a history problem. It needs to be integrated across all different disciplines.”