Study: Climate change is pushing the Sonoran Desert toward a weedier, barren future

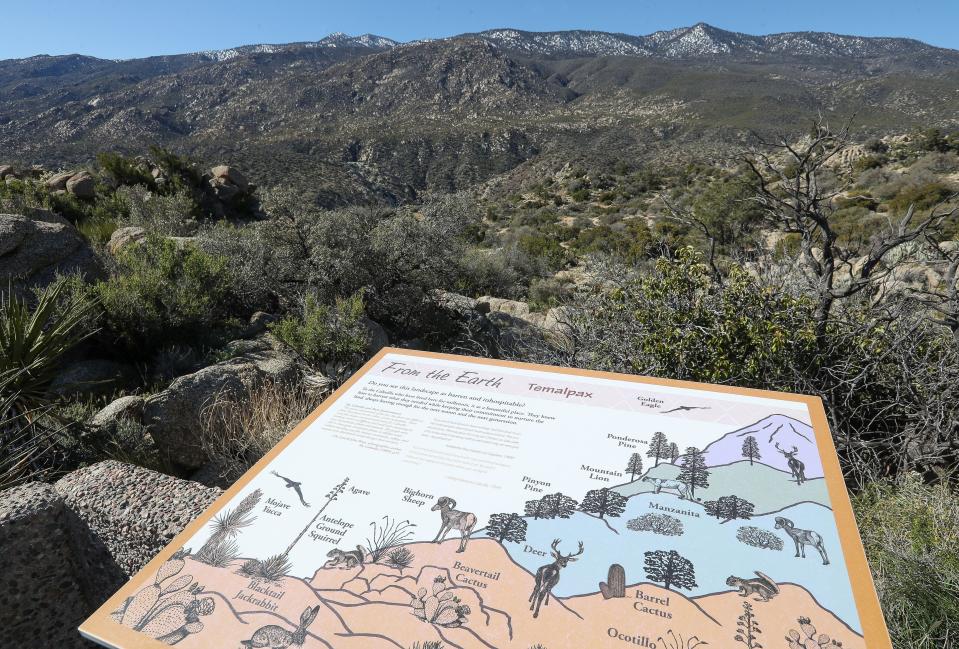

From pinyon pines to ocotillos, plants in the Sonoran Desert are shifting where they grow in response to climate change, and many of the plants aren’t thriving in their new ranges, according to a new study from researchers at the University of California, Riverside.

The study, published in the journal Functional Ecology in March, focused on observations by the research team at the Boyd Deep Canyon Desert Research Center, located south of Palm Desert and east of Highway 74 in the Sonoran Desert, in 2019. The Sonoran Desert covers the southeastern corner of California, including the Coachella Valley, and stretches into southwest Arizona and the Mexican states of Sonora, Baja California, and Baja California Sur.

Researchers traveled from the top to bottom of an 8,000-foot research area that stretches from the desert to the mountaintops, and through a range of plant communities, from desert scrub plants to pinyon-juniper woodlands to coniferous forest. The same research area was examined by ecologists in 1977 and 2008, which was used as a basis to compare with the recent findings.

The study’s analysis of nearby weather station data showed “substantial warming trends” across elevations in the Boyd Deep Canyon research area, with annual minimum temperature increasing by 2.77 degrees Celsius at the lowest elevation transect, 3.84 degrees Celsius at the middle elevation, and 2.3 degrees Celsisus at the highest elevation from 1947 through 2018. One degree of Celsius is the equivalent of 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit, so annual minimum temperatures went up by between 4.14 and 6.9 degrees Fahrenheit, depending on the elevation.

While many studies have shown how hotter and drier temperatures are redistributing plant species in alpine regions and mountain ranges, the UC Riverside study demonstrated that even hardy desert ecosystems long thought to be tolerant to stressors like drought and heat are feeling the impacts of climate change and warming temperatures, possibly even more so than some other ecosystems.

“We tend to think of deserts as super resilient, and there’s been a general mentality that surely climate change isn’t going to impact these ecosystems that are already kind of living on the edge in places that are hot and dry, but what global research is now finding and our research is supporting is that these ecosystems are actually very fragile, and they’re actually responding really quickly to changes in climate,” said Tesa Madsen-Hepp, first author of the study and a doctoral candidate in evolution and ecology at UC Riverside.

Pinyon pines and junipers are declining

The result of climate change on the desert ecosystem could be a weedier and more barren landscape, as taller trees and plants shift to higher elevations and decline in numbers, while smaller brush-like plants fill in the gaps.

Globally, plants are moving to higher elevations in search of cooler temperatures in response to the warming climate. The ranges of plants in temperate regions have shown shift rates of between 5 and 30 meters a decade on average. But in the Boyd Deep Canyon research area, plants are shifting their ranges upwards at a rate of about 29 meters per decade, the higher end of global rates for plant movement in response to climate change. With one meter equal to about 3.28 feet, this means local plants are moving upward at a rate of about 95 feet per decade.

Some of the plants that are shifting upward include the desert apricot, pinyon pines and juniper trees. And while they’re extending their range upward, this doesn’t mean the overall numbers of these plants are increasing, as it seems like they’re “reaching their threshold in terms of the amount of aridity they can handle,” Madsen-Hepp said.

“Even though they're increasing in terms of where they're distributed, they’re decreasing in terms of how abundant they are. So their overall prevalence at those elevations is actually lower, and the populations are essentially shrinking,” Madsen-Hepp said.

Researchers expected to find that local plants were shifting upwards in elevation, although maybe not quite as quickly as 29 meters per decade. But they didn’t expect to find that other plants are actually shifting down to hotter elevations, extending their ranges downward.

Shorter and “weedier” plants with more shallow root systems like brittlebush, burrow bush, and ocotillo are filling in the gaps left as taller trees and other plants move to higher elevations. These plants can more easily drop their leaves in response to stressful drought conditions, and also don’t rely as much on increasingly scarce deep soil water. This shift has wide-ranging implications for the Sonoran Desert.

“We all get sad about the species we know and love that are potentially declining, but I think the ecosystem-level ramifications of this are really important to emphasize,” Madsen-Hepp said.

Desert could be nearing an 'ecological breakdown'

Taller species provide habitat for both animals in the desert and create shadier microclimate conditions for other plants to establish themselves and grow from seeds, Madsen-Hepp said, with vulnerable young plants often relying on taller nearby plants in order to start growing. This means the decline of taller species in parts of the Sonoran Desert could in turn result in a “feedback effect” of a decline in the establishment of new baby plants of other species.

But Madsen-Hepp also says that other global studies have found that the types of big ecosystem changes that are currently underway in the Sonoran Desert have been associated with “an ecosystem breakdown response” in which plants reach their limit of how much aridity they can handle, resulting in a barren landscape where plants can’t survive.

“I think it is really a really big alarm and a cause for concern that this system might be approaching that point,” said Madsen-Hepp. “So other than just the aesthetic change of the desert, it's a really big transition that we're seeing and that is potentially associated with an ecological breakdown of sorts.”

And somewaht ironically, the havoc being wrecked on desert ecosystems by climate change could also worsen climate change, in the way that the impacts of climate change can often worsen climate change through feedback loops. The desert shrubs capture and store less carbon than the pines and other plants they’re replacing.

The study’s authors say there’s a clear solution to reducing the threats to the Sonoran Desert.

“We often think of the tundra as the bellwether for climate change. Arctic and alpine ecosystems are very sensitive. We’re seeing here that this ecosystem is just as sensitive if not more so,” Marko Spasojevic, senior author and assistant professor in UCR’s Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology, said in a press release. “And we already know the answer to easing the stress on it. It’s very simple. Cut fossil fuel emissions.”

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Climate change threatens Sonoran Desert plants, new study finds