Study discounts belief 1918 flu pandemic targeted healthy young adults

Oct. 9 (UPI) -- New evidence from the remains of 1918 influenza victims contradicts a long-held belief that healthy young adults were disproportionately affected during that pandemic more than a century ago.

Researchers at McMaster University and the University of Colorado Boulder announced Monday that there is "no concrete scientific evidence" to support historical accounts that the healthy were as likely to die from the flu as those who were already sick or frail.

The study, which focused on the relationship between socioeconomic status and mortality, analyzed lesions on 369 victims' bones and their age at death. Researchers found those most susceptible to dying from the 1918 flu already had shown signs of nutritional, environmental and social stress.

"Our circumstances -- social, cultural and immunological -- are all intertwined and have always shaped the life and death of people, even in the distant past," said Amanda Wissler, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at McMaster and lead author of the study published Monday in the journal PNAS.

"We saw this during COVID-19, where our social backgrounds and our cultural backgrounds influenced who was more likely to die, and who was likely to survive," Wissler added.

Pre-existing medical conditions, such as asthma or congestive heart failure, remain common risk factors to this day with the flu or other infectious diseases.

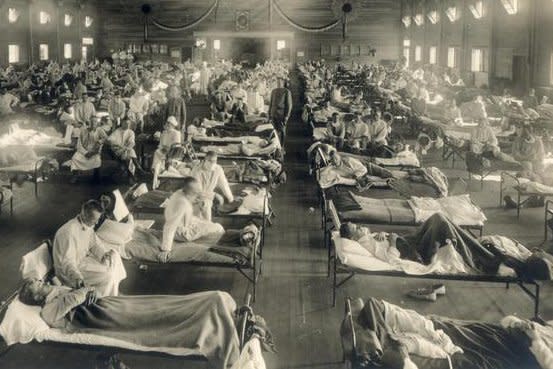

The 1918 flu pandemic killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide. With so many people falling ill and dying, physicians at the time believed the healthy were just as likely to die from the flu.

But researchers in the PNAS study found signs of pre-existing poor health, including irregular growth, diminished height, tooth defects, or lesions -- caused by physical trauma or infection -- in a larger percentage of the bones of those who died during the influenza pandemic.

"By comparing who had lesions, and whether these lesions were active or healing at the time of death, we get a picture of what we call frailty, or who is more likely to die. Our study shows that people with these active lesions are the most frail," Sharon DeWitte, biological anthropologist at the University Colorado Boulder and co-author of the study, said in a statement.

According to researchers, racism and institutional discrimination can amplify the life and death impact of preexisting medical conditions during a pandemic.

"The results of our work counter the narrative and the anecdotal accounts of the time," said Wissler. "This paints a very complicated picture of life and death during the 1918 pandemic."