Study of over 1,300 world languages finds which ones are most complex and why

Societies formed of non-natives and strangers do not speak less complex languages as previously held, according to a new study that sheds more light on the factors that influence the grammatical complexity of a language.

Across the world, languages widely differ in how many grammatical distinctions they have for expressing different thoughts.

This is observable even between closely related languages such as Swedish, Danish, and Norwegian.

For instance, in these languages, the same word hunden, meaning “the dog”, is used to communicate that the dog is in the house or that someone found the dog or gave food to the dog.

However, in Icelandic, three different word forms would be used in these situations, corresponding to the nominative, accusative, and dative case respectively: hundurinn, hundinn, and hundinum.

Such a distinction sets Icelandic apart from its closely related sister languages.

Until now, one prominent hypothesis about why some languages show more complex grammar than others links grammatical complexity to the social environments in which these languages are used.

Icelandic, for example, is primarily learned and used by the local population of over 350,000 people – a relatively small isolated community of so called “societies of intimates.”

On the other hand, other Scandinavian languages located in close proximity to their neighbours have larger populations with substantial proportions of non-native speakers, making up a “societies of strangers.”

Since the members of homogenous esoteric societies rarely communicate with outsiders, researchers have held that the languages in such societies are acquired and used almost exclusively by its members.

Due to a lack of contact with nonnative speakers in such societies, these communities are thought to develop and retain more obligatory explicit grammatical markings.

Linguists have also held that languages with more non-native speakers tend to simplify their grammars.

They have reasoned that this is because unlike children, adult learners tend to struggle to acquire complex grammatical rules.

“For instance, since the Old English period, English has lost the adjective agreement in case, number, and gender as well as the nominal case distinctions, which has been linked to the adoption of English by nonnative speakers,” researchers explain.

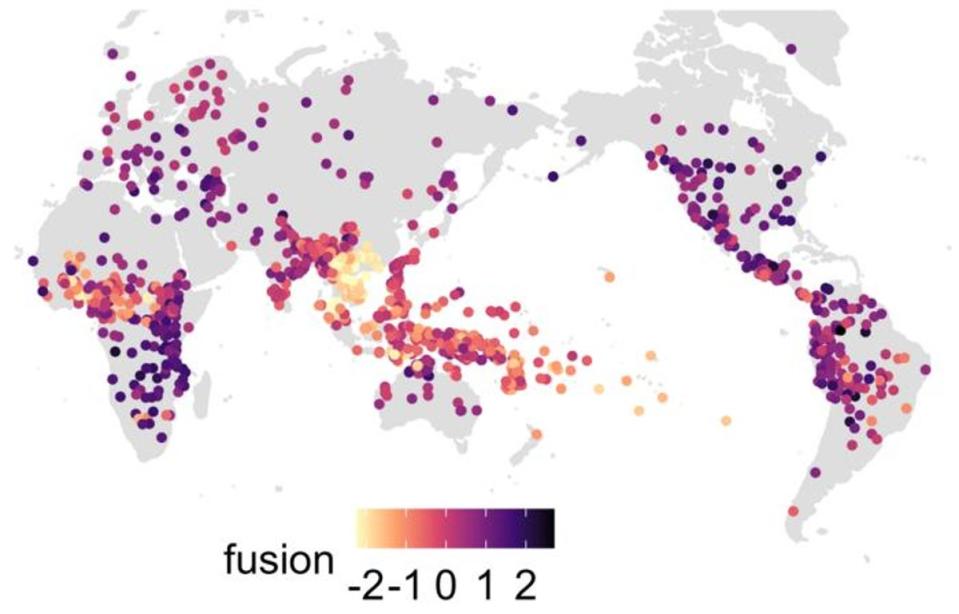

In the new study, scientists from Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology tested this hypothesis by estimating the grammatical complexity of 1,314 languages across the world and comparing them to a measure of the number of non-native speakers in these languages.

Many of the disagreements, researchers say, are down to differences in how ”complexity” is defined.

A language can become more complex over generations as it increases the number of “grammatical cases and determiners, irregular verb forms, noncompositional constructions, agreement patterns, and/or phonologically fused markers expressing different functions.”

But different underlying mechanisms can be responsible for changes in each of these dimensions of complexity in exoteric societies.

The findings reveal that “societies of strangers” do not speak less complex languages.

“Instead, our study reveals that the variation in grammatical complexity generally accumulates too slowly to adapt to the immediate environment,” study co-author Olena Shcherbakova said.

As a counter example to the currently held theory, scientists say German is learned and spoken by a large number of non-native speakers and yet, it retained its case system and many other grammatical distinctions.

“Our study highlights the significance of using large-scale data and accounting for the influence of inheritance and contact when addressing long-standing questions about the evolution of languages,” Simon Greenhill, another author of the study from the University of Auckland in New Zealand said.

“It shows how received linguistic wisdom can be rigorously tested with the global datasets that are increasingly becoming available,” Dr Greenhill said.