Study: Right whale decline 'leveling out,' but species hasn't turned the corner yet

Researchers have just released their latest population estimate for critically endangered North Atlantic right whales, and while there is some cause to feel encouraged it's tempered at best.

The study "is basically saying the rate of decline is leveling out," said Philip Hamilton, a senior scientist at the New England Aquarium Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life and the identification database curator for the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium.

He cautioned it's not time to break out the champagne and celebrate. The population remains teetering on the edge of recovery and descent toward extinction without concerted efforts by humans to protect them.

'Not turning the corner yet'

The population is not turning the corner yet, Hamilton told the Times. "That would be good news," he said.

Heather Pettis, a research scientist in the Anderson Cabot Center and the executive administrator of the consortium, pointed out the data shows human activities "are killing as many whales as are being born into the population, creating an untenable burden on the species."

According to Hamilton, the numbers of deaths from these human-made causes — entanglement in traditional fishing gear and vessel strikes — remain high.

To reach a turning point what's needed is an increase in reproduction which has been low for a number of years.

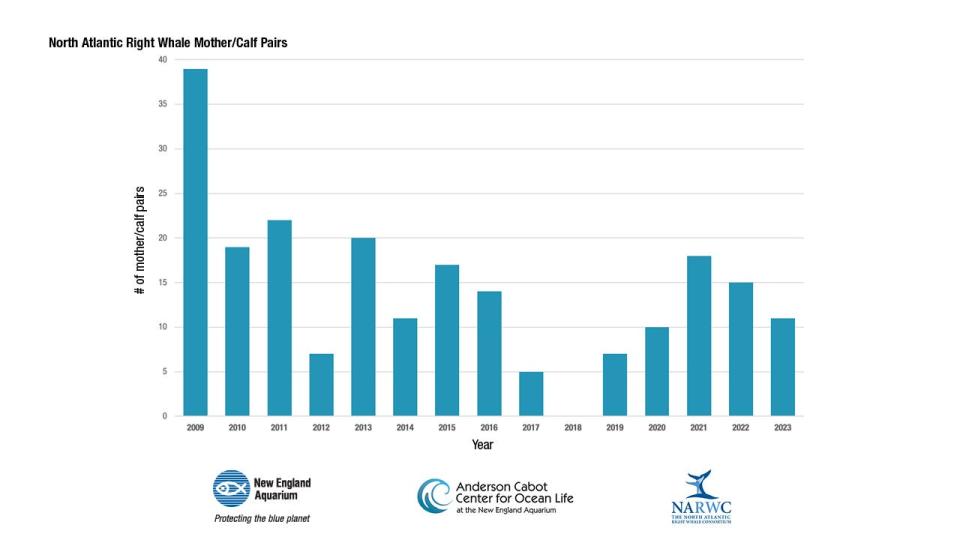

Charles "Stormy" Mayo, director of the right whale ecology program at Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown, told the Times earlier this month it was satisfying to see 11 calves born into the population this year, but he noted it's still too low a number, and there aren't that many potential mothers left. One of the newborns also did not survive.

Birth rate remains a concern

At present, there are fewer than 70 actively reproductive females among the 356 — plus or minus seven — estimated right whales. Among those females, Hamilton said, 41 are between the ages of 10 and 20 that have not yet given birth. That is worrisome.

"In the past, the average age of first reproduction is 10," he said.

The trend shows a large number of females are either experiencing delayed start of reproduction because of environmental stresses and failure to thrive, to the point where they are unable to successfully carry a calf to term. Some of them may not give birth at all. Also, scientists are observing a greater interval of time between births among the reproductively actively females.

In the 2000s, there was an average of 24 calves born per year, Hamilton said. "Now it's very erratic," he noted.

Compared to this year's 11 calves, in 2022 there were 15 calves born and in 2021 there were 18

Right whales are not growing as big, which Hamilton said scientists are still trying to understand. That could be connected to a combination of sublethal injuries from entanglement and lack of proper nutrition.

Whales remain threatened by human activities

"We also need to see a reduction in deaths and injuries from human causes," said Hamilton. Only about two thirds of the deaths are detected, he said.

This year, scientists have detected 32 right whales with injuries. Thirty of those are injuries from entanglements, with six of the whales still carrying gear, Hamilton said. Two of the injuries noted are from vessel strikes.

"Those are injuries that could lead to death or dysfunction," such as a whale's inability to feed properly and have the strength successfully to reproduce.

"This is an important piece of the right whale puzzle. We can’t just focus on (detected) bodies. We must also reduce all injuries that harm this species if they are to turn the corner,” said Hamilton.

Mayo recenty told the Times he won't feel encouraged about the outlook for right whales "until the mortalities are clearly down and the birth rate is up."

"It's going to be a long time before we are out of the hole," he said.

Population estimate recalculated

Each year, the consortium releases the annual population estimate for the species using the most up-to-date data, including calves added to the population since the previous year, according to a release about the study.

Scientists used these updated data to recalculate annual estimates of the right whale population since 1990, according to the New England Aquarium.

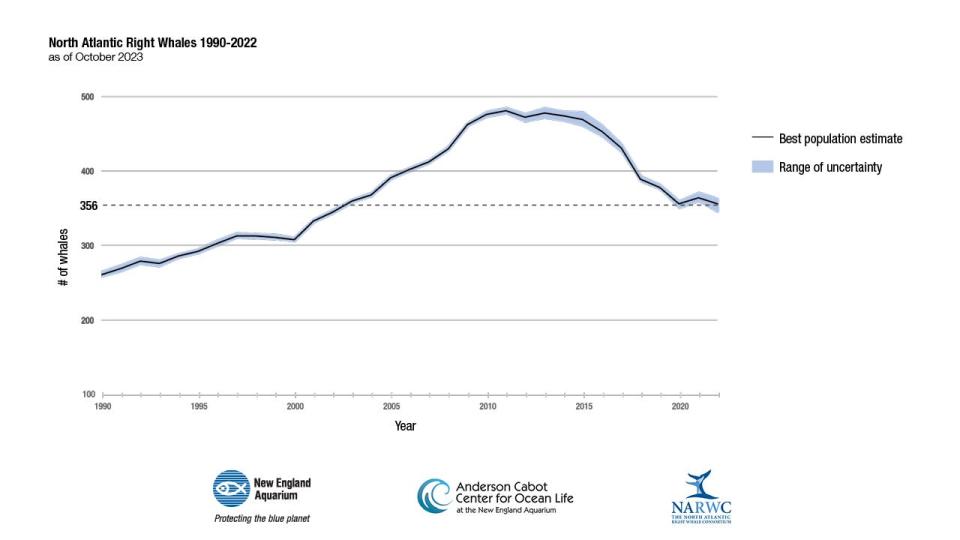

"The 2021 estimate was recalculated as 364 (+5/-4 for range of error) — primarily due to the 18 calves born in 2021, many of which were recently catalogued — and the 2022 estimate is 356 animals (+7/-10), suggesting the downward trajectory for the species could be slowing," the researchers indicate.

Scientists from the Anderson Cabot Center and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration collaborated on the population estimate.

Even though there were some upward adjustments from previous years, Hamilton stessed that it's not so much the numbers of whales scientists are looking at.

"We're really trying to encourage people to focus on the trend of the graph," he said.

So far this year, there have been two detected right whale deaths: a 20-year-old male that was struck and killed by a vessel, and an orphaned newborn calf.

Although having just two documented deaths this far into the year may seem like good news, Hamilton pointed out that about two thirds of North Atlantic right whale deaths go undetected.

"Additionally, there continue to be elevated numbers of human-caused injuries to this population. The impacts of these injuries from fishing gear entanglements and vessel strikes, the leading causes of the North Atlantic right whale’s decline, are delayed when calculating the species’ population size," according to the New England Aquarium.

“We continue to injure and kill these whales at alarming rates, such that they cannot carry out basic biological functions like growth and reproduction. While the absolute population numbers are important, other indicators are discouraging. Until we implement strategies that eliminate injuries and deaths, and promote right whale health, this species will continue to struggle,” said Consortium Chairman Dr. Scott Kraus in the release.

The researchers are particularly interested in what's going to happen with the 40 females who are still alive but have not given birth yet, Hamilton said.

The overall message they want to convey, he said, is that the news for right whales is "better than it's been, but it's still not good news."

"The focus needs to be on the things we can control, which is human-caused injury and death. The injuries are the big thing. They are very high," Hamilton said.

According to the researchers, "advances in ropeless or 'on-demand' fishing technology show promise, though widespread implementation will require significant financial support to escalate the manufacturing of the gear and provide training and support for the fishing industry to adopt gear use."

NOAA has also been working to develop vessel speed restrictions to better protect right whales "while ensuring both the species and economy thrive."

The consortium plans to highlight the new population study at its annual meeting Tuesday and Wednesday in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Following the meeting, the consortium plans to draft a comprehensive annual report on the status of the species; survey, management, and research activities, and recommendations for action. The report will be available early in 2024 and published on the consortium website.

When might right whales next be seen in Cape Cod Bay?

It's getting close to the time of year when right whales will start to return to Cape Cod Bay, and they will continue streaming in through spring.

"They will start showing up in December in Cape Cod Bay," Hamilton said.

The latest right whale observations can be reviewed on WhaleMap.org. As of Monday there are no right whales in Cape Cod or Massachusetts bays, though one whale was spotted near Georges Bank, east of Cape Cod, on Oct. 17. Most recent sightings are in the Bay of Fundy, Canada.

Heather McCarron writes about climate change, environment, energy, science and the natural world, in addition to news and features in Barnstable and Brewster. Reach her at hmccarron@capecodonline.com.

Thanks to our subscribers, who help make this coverage possible. If you are not a subscriber, please consider supporting quality local journalism with a Cape Cod Times subscription. Here are our subscription plans.

This article originally appeared on Cape Cod Times: Right whale decline 'leveling out,' but concerns remain, study shows