A suburban Chicago insurance agent won a contest 40 years ago to make the first commercial cellular call. He’s still on the phone

There are more than 300 million cellphone customers in the U.S.

David Meilahn, a suburban Chicago insurance agent, was the first.

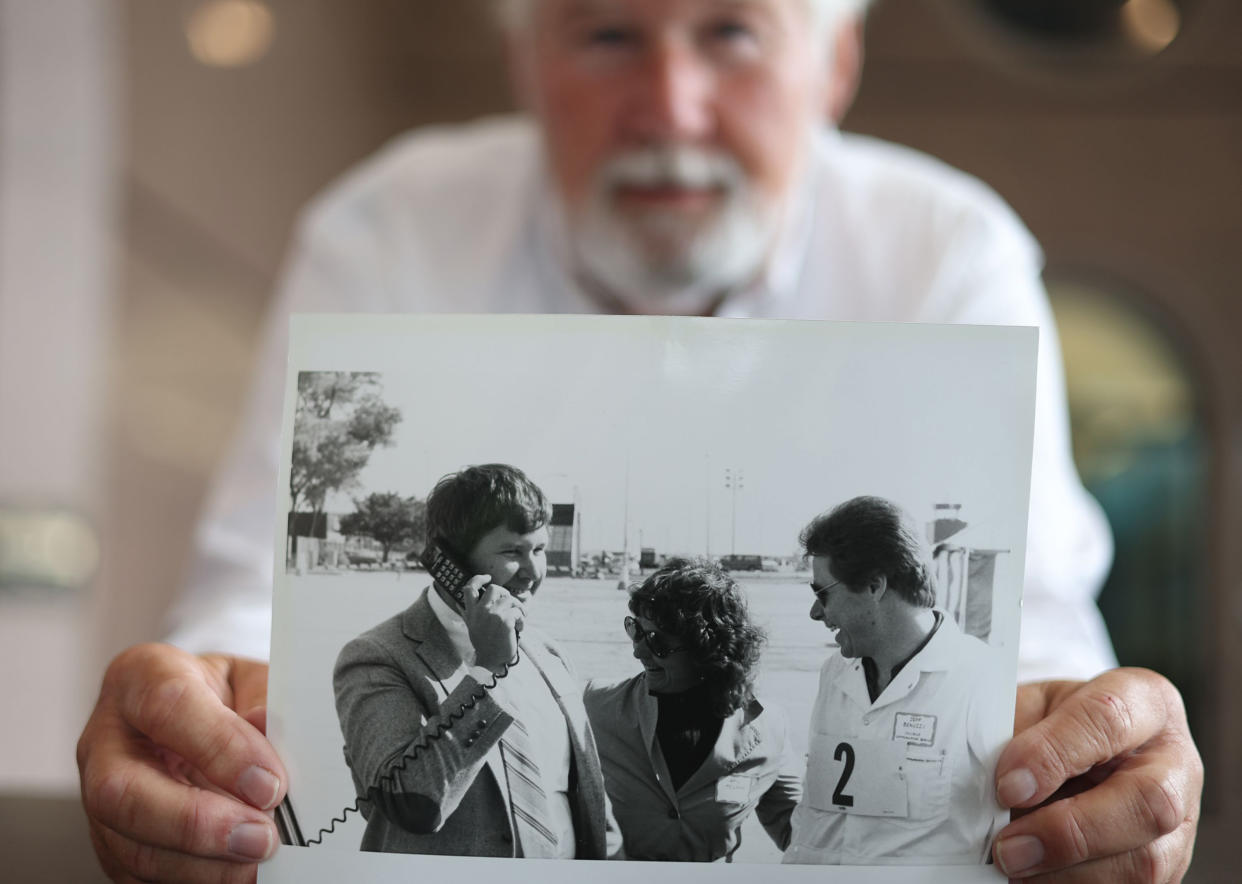

In a Soldier Field parking lot, 40 years ago Friday, Meilahn bested 13 other early adopters in a promotional race to see who could activate their preinstalled car phones and make the first commercial cellular call in the U.S.

Meilahn won a check to cover the car phone’s cost and a footnote in the history of the transformational wireless telecommunications industry.

There was even a “Jeopardy” answer about his accomplishment — you can look it up on your smartphone.

“This was part of my 15 minutes of fame,” said Meilahn, 74. “Everybody thought it was really a neat novelty that I became the first cellular phone call. But it wasn’t as important the first year as it is today. It’s just part of every person’s life.”

In days of yore, before phones were smart, they were tethered to walls and going mobile meant stretching a tangled cord across the room. All of that changed on Oct. 13, 1983, when Ameritech Mobile Communications, then a subsidiary of AT&T, launched the first commercial cell service in Chicago.

Chicago was both the birthplace of the cellphone and the epicenter of the nascent technology’s development. In 1973, Motorola executive Martin Cooper made the first cellular call in New York with a brick-like prototype built by the then Schaumburg-based company. Engineers at AT&T’s Bell Laboratories built out an experimental system in the Chicago area in the late 1970s, refining a network to hand off calls as users traveled from one cell to the next.

In June 1983, Ameritech filed an application with the Federal Communications Commission to turn the experimental cellular network into a commercial one. The Ameritech system covered a 2,500-square-mile area across the Chicago metro, providing service from Lake Forest to Geneva to Beecher. It got the green light from the FCC on Oct. 6 and went live one week later.

Ameritech decided to launch the service with an over-the-top publicity stunt, inviting 14 contestants to participate in a tag-team race to make the first commercial cell call.

Contestants stood by their cars while technicians ran across a Soldier Field parking to install a chip and activate a mobile transceiver in the trunk. The drivers then hopped in and placed a call to another car in the lot, where Robert Barnett, president of Schaumburg-based Ameritech Mobile Communications, was waiting to answer.

Cubs announcer Jack Brickhouse was on hand to provide the play-by-play of the event dubbed “The Great Cellular Race.”

Meilahn, who owns an insurance agency now based in west suburban Oakbrook Terrace, won the race. His fleet-footed partner was technician Jeff Benuzzi.

A River Forest native, Meilahn had been using a radio phone in his car to close insurance deals on the fly. When his car was stolen out of a Burnham Harbor parking lot in the summer of 1983, he bought a new vehicle and went to get another radio phone. His installer recommended he go with the newfangled cellular service being tested by Ameritech, even if it meant waiting a few months before the system was up and running.

After the cellphone was installed, Meilahn got the invite to participate in the promotion.

Benuzzi told Meilahn that he might not be the fastest across the lot, but that his experience would allow him to seat the chip properly and quickly. Once completed, he would hand the keys to Meilahn to start the car and fire up the phone.

The other piece of advice Meilahn received was to wait until all of the lights on the phone were done flashing before trying to place the call. He entered the number but didn’t hit send until the phone was fully booted. The other phone rang, and Meilahn got the good news from Barnett.

“There was just a simple ‘Hello, congratulations,’ as I recall,” Meilahn said.

At some point during the event, Barnett also placed the first international cell call, to one of Alexander Graham Bell’s grandchildren.

Meilahn was feted with a post-race celebration under a tent and was awarded an oversize check for $2,809 to cover the cost of his mobile cellphone equipment and installation. The actual bill, it turned out, was higher, but Meilahn appreciated the windfall nonetheless.

“I think I paid around $3,600 — they were very expensive at the time,” Meilahn said. “But they presented me with this large check and, technically, they were giving me a free phone for having won the race.”

It many ways, it was a call heard round the world in the rapidly changing telecommunications industry.

In January 1984, AT&T was broken up into eight companies by federal regulators to settle an antitrust lawsuit. AT&T kept its long-distance and equipment manufacturing businesses, while seven regional “Baby Bells” took over local calling operations, with Ameritech covering Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin and Ohio.

Ameritech also kept the pioneering mobile phone service, which evolved into a major regional and eventually, national player. In 2000, it became part of Verizon, a company formed by the merger of Bell Atlantic and GTE, which had purchased Ameritech Cellular only months earlier.

AT&T, whose history dates back to Bell’s invention of the telephone in 1876, reemerged during the new millennium as a diversified telecommunications giant with everything from mobile phones to pay TV. In 2005, AT&T was gobbled up by SBC, a renamed former Baby Bell whose holdings included the 5-year-old Cingular wireless service. The merged company kept the AT&T name.

In 2006, AT&T acquired BellSouth, another former Baby Bell that had partnered in Cingular. With ownership consolidated, it changed the name of the wireless service to AT&T in 2007, establishing one of three dominant cellphone companies in the U.S.

Verizon had 114 million pre- and postpaid mobile phone customers at the end of the second quarter this year, followed by T-Mobile at 95.6 million and AT&T at 87.9 million, according to industry analysts MoffettNathanson.

Chicago-based U.S. Cellular, the former namesake of the White Sox ballpark now known as Guaranteed Rate Field, is a distant fourth with 4.1 million mobile customers, according to MoffettNathanson.

The growth of cellphones far exceeds what Barnett and Meilahn imagined during the launch 40 years ago.

During the 1983 race event, Barnett said business users were the target customer, and predicted that 300,000 people in Chicago and 3 million nationwide would want cellular service “in the very near future” as it expanded to other markets, according to a video interview.

At the same time, Barnett tamped down speculation that cell service would replace traditional landline phones.

“We don’t see at this point in time that it would replace the telephone service that we know ordinary residential customers have,” Barnett said.

Over the years, Meilahn progressed from an installed car phone to a handheld device, and has also made the transition from analog to digital, which dramatically improved the quality of cellular calls. But the biggest evolution was the advent of the smartphone, which turned it into a ubiquitous multimedia device, and an indispensable 24/7 appendage for many users.

He currently uses an iPhone 14.

Meilahn also migrated through several carriers as they merged and reemerged over the years, including Ameritech and Verizon. He signed up with AT&T last year, bringing him full circle to the parent company where it all started 40 years ago.

His 15 minutes of fame, which included local and national media coverage, has occasionally bubbled back to the surface over the past four decades. The call, for example, was a “Jeopardy” answer in 2017 under the category Invention & Discovery.

It read: “On Oct. 13, 1983 David Meilahn & Bob Barnett made the first calls on a commercial one of these, talking to Bell’s grandkid.”

Others are less impressed by his accomplishment. When shopping for a new phone, his wife, Gail, invariably tells the salesperson that Meilahn made the very first commercial cell call in the U.S., a feat which he said is lost on a younger generation raised on smartphones.

The salespeople generally respond with, “What color do you want?” he said.

Meilahn also touts the groundbreaking call on his insurance agency’s website. But even he initially thought the cellphone might be short-lived.

“In the beginning, no one knew it was going to be here 40 years later,” Meilahn said. “I honestly believed that something was going to come to replace cell service at some point in time.”

These days, Meilahn is just one of 300 million-plus cellphone users in the U.S., albeit the only one with 40 years of history and the savvy of a septuagenarian.

As such, he has a piece of advice for those customers who have followed in his footsteps.

“You go to a restaurant and you see four people at a table and they’re all on their cellphone looking at something,” Meilahn said. “Don’t forget to have a conversation. But it’s just a wonderful tool. You can’t live without it, really.”