Is the Super Bowl getting hotter? Temperature trends are rising, especially in Phoenix

When the New York Giants kicked off against the New England Patriots to start Super Bowl 42 at the Cardinals' new stadium in Glendale, Arizona on Feb. 3, 2008, the temperature outside was 59 degrees Fahrenheit. The Patriots lost that matchup 14-17 after an improbable late comeback by Giants quarterback and game MVP Eli Manning.

Seven years later, when the game returned to Arizona's State Farm Stadium on Feb. 1, 2015, the Patriots claimed redemption in a victory against the Seattle Seahawks, 28-24. That game kicked off with an outdoor temperature of 68 degrees. That's just one degree warmer than the high on Jan. 28, 1996, when the Dallas Cowboys defeated the Pittsburgh Steelers 27–17 in Tempe the first year Arizona hosted the Super Bowl.

On Sunday, when the Kansas City Chiefs face the Philadelphia Eagles in Super Bowl 57, temperatures in sunny Glendale are projected to be around 65 degrees.

By themselves, these four data points mean nothing about a complex, warming climate or changing conditions for America's most popular professional sport, especially since State Farm Stadium can be enclosed with a retractable roof and climate controlled for game day to protect players and spectators from the elements.

But zooming out to view temperature changes in Super Bowl host cities over the history of this winter sporting tradition paints a more complete and perhaps a sweatier picture about the future of athletics in a warming world.

Scientists at Climate Central, a nonprofit climate communication organization, compiled data on how much average warming has occurred between 1966 and 2016 (when they released their findings) in each of the cities that have hosted the Super Bowl. They found that every single Super Bowl host city has seen an increase in average temperatures over that 50-year timeframe.

Owing to different vulnerabilities to warming based on where in the country the city is located, there is a wide range in temperature trends across the league. Charlotte has warmed an average of 1.3 degrees. A typical day in 2016 in Denver is 1.1 degrees warmer than typical days there in 1996. San Diego, kept more moderate by its proximity to the Pacific Ocean, has warmed just 0.1 degree on average.

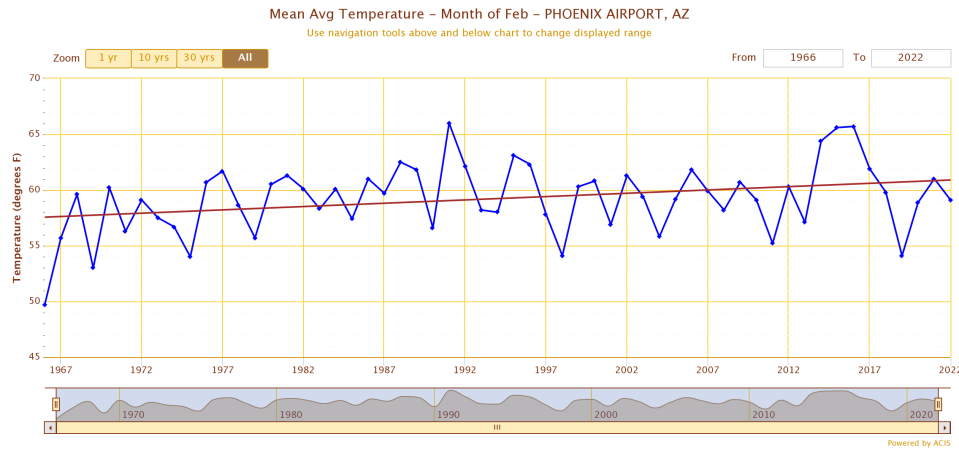

And then there's Phoenix. Out of all the cities where the football championship has taken place, Climate Central found that the Arizona capitol has warmed the most, with recent average temperatures 5.1 degrees warmer than when the very first Super Bowl was played. That number has risen further by 2023 with the escalating pace of climate change. Although the rate of increase has slowed in recent years, the amount of fossil fuels burned for energy globally is still trending upward, while progress related to the political adoption of pollution restrictions and renewable energy solutions lags. The resulting emission of harmful greenhouse gases, which trap and hold heat from the sun in the atmosphere, may change what it means to play in or spectate future Super Bowls.

Gripping reality: Heat puts players at risk

State Farm Stadium was built with intemperate weather in mind. The entire facility can be enclosed and air-conditioned, so exertional heat illnesses are probably not high on the list of concerns for this year's Super Bowl players and coaches.

But with exertional heat death counts going up among athletes training and performing in a warming world, exercise physiologists do worry about how climate change will affect the future of the sport.

“On average, between high school and college athletics, we see between six and seven heat-related deaths per year in the U.S," Rebecca Stearns, an exercise physiologist at the University of Connecticut and COO of the Korey Stringer Institute that studies and raises awareness about exertional heat stroke, told The Arizona Republic in August.

Heat and athletics:Exertional heat stroke is on the rise for athletes. Could tracking urine be the answer?

A majority of those heat exertion deaths are among football players.

"Football linemen have a lot of muscle mass," Stearns said. "When you have individuals that are that large and you put a lot of equipment on them and have them do short, intense bursts of sustained exercise over time, you're going to drive their body temperature up."

Korey Stringer was a Minnesota Vikings offensive lineman who died from exertional heat stroke in 2001. The Institute founded in his name partners with the National Football League, Gatorade, the National Athletic Trainers' Association and others to better understand and manage heat risks to athletes. Even the most fit, trained and experienced players can fail to heed the warning signs, Stearns said.

Sometimes their commitment to the sport, instead of just making them more seasoned and aware, can put them at greater risk of pushing past warning signs in high-stakes championship games like the Super Bowl, when they aim to leave it all out on the field.

“A lot of times people don’t have any warning that they’re going to have a heat stroke," Stearns said. "They’re so focused and driven that they don’t even realize, and they have no memory of the last 10 to 20 minutes."

More:How marine heat waves in Hawaii have ripple effects all the way to Arizona

Lauren Casey, a meteorologist working with Climate Central, examined average temperatures in February in Phoenix over time and concluded that, while high temperatures don't show a notable increase, average temperatures definitely do. This trend could eventually affect players in local football playoffs at all levels, burdened by layers of protective equipment and motivated to give the game their all.

"The National Weather Service advises caution during physical exertion when the heat index hits just 80 degrees," Casey wrote in an email. "Though it may feel great to fans, even relatively pleasant warm temperatures can be potentially dangerous for the athletes on the field, particularly as more games are played in warm weather due to climate change."

Huddling up: How temps affect Chiefs, Eagles

Bundling up for winter football championships is also part of the tradition for spectators.

"You see the playoff games, often it’s snowing," said Payton Major, an enthusiastic football fan and undergraduate student at Arizona State University majoring in broadcast journalism and meteorology.

"I really do like football," she said. "I think weather and sports is something that should be correlated more. If you watch any kind of sporting events outdoors, you hear the announcers talking about the weather and if it’s raining, there’s always shots of the crowds and the rain and how it’s impacting the game."

More:Climate experts say the world 'is at a crossroads,' but offer hope with concrete actions

Major is part of a group of ASU journalism students who produced a broadcast for their student site, Cronkite News, about how temperatures on Sunday might influence the outcome of the game.

During the current season, the Chiefs have played in more varied temperatures than the Eagles have, the students found. For the Chiefs, the average high during games since September was 61 degrees, while for the Eagles that number was a cooler 58. Average lows during games for the Chiefs was 39 compared to 43 degrees for the Eagles.

But the Eagles performed better at higher temperatures this year. All of their losses happened on days when the low was below 40 degrees, while the Chiefs lost two games on days at or above 60. Both teams do also have a record of winning games in Arizona on hot days, at 90 degrees for Philadelphia and at 103 for Kansas City.

Although Phoenix logs more high temperatures than any other Super Bowl host city overall and has warmed more over time, Major noted that last year's Super Bowl in Los Angeles was the warmest on record and not likely to be matched in Glendale this year.

"I think the high on game day last year in L.A. was 85," Major said. "And they had to play in those conditions. It’s going to get warmer and these players are going to have to prepare for a warmer condition environment rather than rain and cold."

Arizona state climatologist Erinanne Saffell will be watching this year's championship from her home, but didn't hazard a guess as to how changing temperatures might affect the game.

“I generally enjoy the Super Bowl regardless of who is playing," Saffell said. "I pay attention to some teams more than others but I don’t have a favorite. I just like to watch a good football game."

The students are putting their money on the Eagles, based on their analysis of how they anticipate the two teams will perform at higher-than-average temperatures.

"We said the Eagles (would win), just because the Chiefs' last three playoff games were below freezing, and two of those games had snow," Major said. "It's probably going to be in the 70s here, or at least close to it. So we figured that might be a little bit of a shock to them. But at least they'll be in the stadium. So it's not just a 'throwing them out in the desert' kind of thing."

Whatever weather Sunday has in store, whether State Farm Stadium is heated, cooled or its roof is open to the Arizona air and sunshine, it may be a preview into how football traditions will play out in warming days ahead.

Joan Meiners is the climate news and storytelling reporter at The Arizona Republic and azcentral. Before becoming a journalist, she completed a doctorate in ecology. Follow Joan on Twitter at @beecycles or email her at joan.meiners@arizonarepublic.com.

Support climate coverage and local journalism by subscribing to azcentral.com at this link.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Climate data shows Super Bowl temperature rising over time