How a Supreme Court case about Andy Warhol's images of Prince could change the face of art

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

WASHINGTON – Illustrator Lizzie DiFiore has a relatively straightforward process to check if anyone has copied her artwork. It often starts with a simple Google search. More often than she would like, DiFiore says, it ends with a "kick in the gut."

For artists like DiFiore, dealing with copycats has become a central part of the job – requiring time away from the sketchpad to delve into a fluid and complicated area of law.

The Supreme Court will hear oral arguments Wednesday in a case that could significantly change how courts interpret and enforce copyright protection. Its decision may have sweeping implications for small businesses like DiFiore's all the way up to the nation's best-known streaming services and the multi-billion movie industry.

"Infringement is happening constantly to artists all the time," said DiFiore, a Massachusetts-based illustrator and president of the Graphic Artists Guild.

Stay in the conversation on politics: Sign up for the OnPolitics newsletter

Granted: Supreme Court to hear dispute over Andy Warhol's images of Prince

Guide: A look at the key questions pending at the Supreme Court

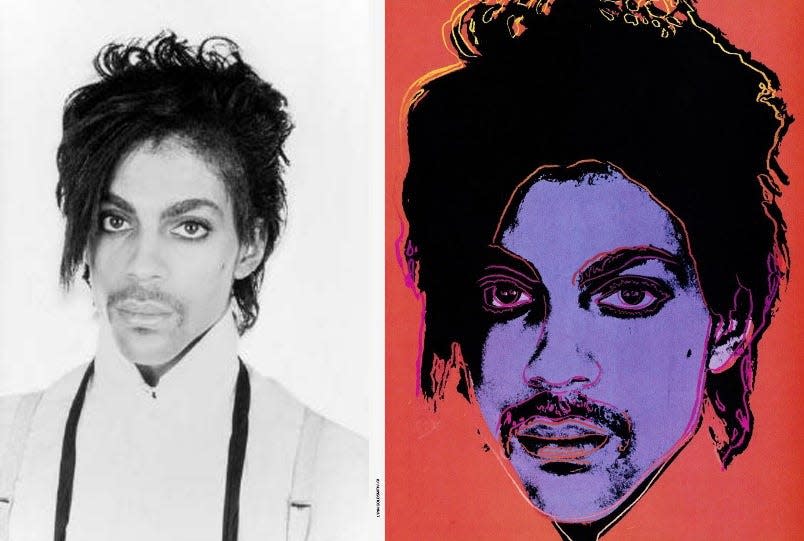

The litigation before the Supreme Court involves one of the country's best-known artists – Andy Warhol – and a rock 'n' roll photographer who asserts that Warhol's colorful silkscreen image of Prince was based too closely on a photograph she took of the musician in 1981, three years before he released his career-defining album "Purple Rain."

Warhol's foundation argues the artwork falls under the fair use doctrine, which permits reproduction of copyrighted material without permission in some circumstances, such as for criticism. The silkscreen, the foundation says, qualifies because it was transformative, changing the message conveyed by the original photograph. Absent a court ruling the Warhol artwork is a fair use, it would likely be deemed a violation of the copyright on the original photograph, resulting in a monetary award to the photographer.

Warhol, Prince and Goldsmith

But the photographer, Lynn Goldsmith, counters that such a standard would make copyright "completely unworkable," in part because it would ask judges to assess the meaning of a derivative artwork and whether it is transformative enough to be deemed fair use. Instead, Goldsmith wants the court to place more emphasis on other factors in the law, such as whether a secondary work and the original are competing for the same customers.

In that scenario, the Warhol foundation could likely still show the Prince silkscreen at a museum but would have to get permission before licensing its use to a magazine, since Goldsmith could also seek to sell her image to the same publication.

How the court balances those arguments could have consequences for art familiar to millions of Americans. Could a musician alter a few lyrics of a Taylor Swift song and escape an infringement suit by claiming a transformation of the song's meaning? On the other hand, might an artist be hesitant to reference another work – say, a musician who wants to sample another song for a remix – if they fear being slapped with litigation?

The case is Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith.

Warhol died in 1987.

"The biggest question around transformative use has been figuring out what kind of test to use to say that it is transformative," said Shyam Balganesh, a law professor at Columbia University and an expert on intellectual property law. "One of the big debates around transformative use is who do we defer to on saying that there's new meaning?"

Copyright: Techies give an old fashioned Supreme Court decent marks in coding case

Tech: Supreme Court sides with Google in years long fight with tech giant Oracle

For DiFiore, those aren't abstract questions. She recently discovered a website selling one of her designs without permission – a fall-themed image of a Shiba Inu puppy sitting inside a pumpkin-shaped mug. She requested that her image be removed and she believes it will be. Her concern is that, if the Supreme Court sides with the Warhol foundation, others might make slight variations and try again.

"It takes such an emotional toll on you," DiFiore said. "On a regular basis, I'm fighting against other people who want to just use my work for free."

'Shine a light on ourselves'

Alfred Spellman, a documentary filmmaker, is on the other side of the debate. In 2014, Spellman produced a documentary miniseries called "The Tanning of America," which explores how the emergence of hip-hop culture changed the way Americans viewed race. The film referenced television shows from the 1970s and 1980s such as "Good Times" and "The Jeffersons" that paved the way for that cultural revolution.

Having to get permission to use every video clip presents a challenge for filmmakers, Spellman said. What if a copyright holder withholds permission because they don't like the film's message?

"Were we to have to clear those or license those, we would be subject to the whims of copyright owners," Spellman said. "You would basically be stifling not only creativity and free expression but also the ability to shine a light on ourselves."

Spellman and other documentary filmmakers are concerned about the standard set by the New York-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, which sided with Goldsmith in the suit last year. Putting the two images of Prince side by side, the appeals court ruled Warhol's piece wasn't transformative because it "recognizably" derived from and retained "the essential elements" of Goldsmith's photograph.

Documentary filmmakers often include source material with no alteration to drive atcommentary about its broader meaning. Preventing that kind of use, Spellman said, "would make it impossible to produce" films like his miniseries on race.

The Supreme Court weighed in on the issue in a landmark 1994 decision involving 2 Live Crew's rendition of Roy Orbison's "Oh, Pretty Woman." A unanimous court sided with the hip-hop group, placing a heavy emphasis on the idea that the parody was "transformative" and so was a fair use under copyright law.

But the Warhol case has arrived at a time when the Supreme Court is far more focused on the text of federal laws and has placed less emphasis on what a law's intent might have been. Because the word "transformative" doesn't appear in the statute some experts wonder if the court may be looking toward a broader overhaul of copyright law in the case.

"The fundamental question in the Warhol case, in my view, is does the different meaning or message in the accused work matter?" said Bruce Ewing, co-chair of the intellectual property litigation practice group at the Dorsey & Whitney law firm.

"Whichever way the court rules here, it will certainly bring needed clarification to a very confused area of the law," Ewing said. "It will also really lay out, we hope, a framework to guide the fair use analysis in the future."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Supreme Court to wrestle with dispute over Andy Warhol image of Prince