The Supreme Court’s Right Flank Is Laying Groundwork to Dismantle Defendant Rights

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is part of Opening Arguments, Slate’s coverage of the start of the latest Supreme Court term. We’re working to change the way the media covers the Supreme Court. Support our work when you join Slate Plus.

“Precedent plays an important role in promoting stability and evenhandedness.” Those were the words of Chief Justice John Roberts at his 2005 confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee explaining the importance of respecting judicial precedent. He went on to say that when weighing whether to overturn an important decision like Roe v. Wade, justices need to consider many factors, adding, “I do think the considerations about the court’s legitimacy are critically important.”

Yet, in the past two terms, Roberts and his five conservative colleagues—the court’s recently developed conservative supermajority—have thumbed their noses at judicial precedent by overturning Roe and by overturning four Supreme Court decisions that upheld affirmative action in college admissions. Entering a new term, it’s important to understand that this is just the beginning. One of the court’s future targets is going to be bedrock principles protecting the rights of criminal defendants.

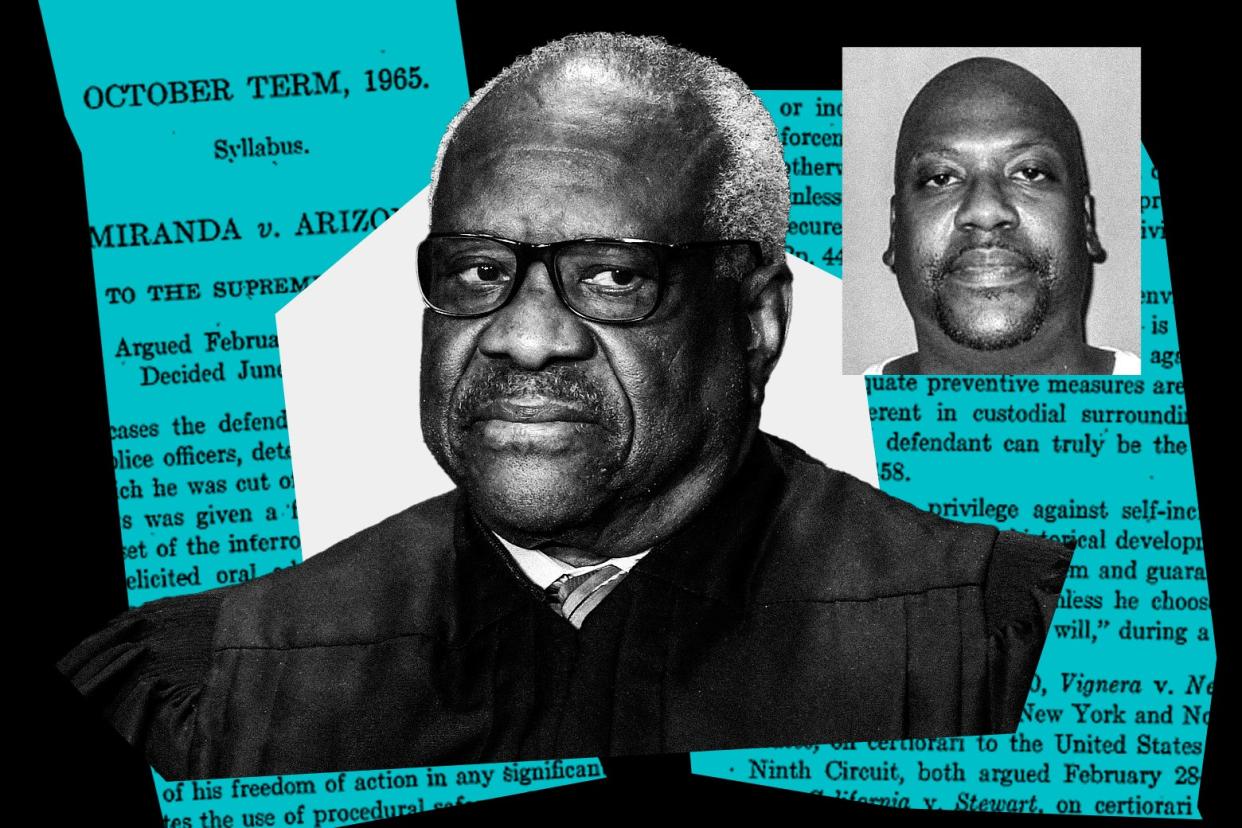

Employing an unholy triad of disrespect for judicial precedent, originalism, and magical thinking, Justices Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Amy Coney Barrett, and Roberts are signaling in their dissents, majority opinions, and concurrences a willingness to overrule landmark Supreme Court decisions that established basic constitutional protections in our criminal legal system. Thomas has led the way in this area. By inviting supplicants to bring these cases back to the court, the supermajority is positioned to overturn them. We should be very alarmed. Here is a short list of the constitutional protections that will soon be under threat.

Nearly 60 years ago, the Supreme Court in Miranda v. Arizona established what is commonly known as the Miranda warning—a requirement that anyone in a custodial interrogation by law enforcement must be advised of their right to remain silent and of the right to have an attorney present during questioning.

In 2000, then–Chief Justice William Rehnquist, a conservative’s conservative, writing for the majority in Dickerson v. United States, declined to overrule Miranda because “stare decisis weighs heavily against overruling it now.” Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by Thomas, dissented: “I am not convinced by petitioner’s argument that Miranda should be preserved because the decision occupies a special place in the ‘public’s consciousness.’ ”

In 2022, Alito, joined by all five of his conservative colleagues, authored a majority opinion in Carlos Vega v. Terence B. Tekoh that, again, questioned the constitutionality of Miranda: “A violation of Miranda does not necessarily constitute a violation of the Constitution, and therefore such a violation does not constitute ‘the deprivation of [a] right … secured by the Constitution.’ ”

Kavanaugh, meanwhile, called for narrowing the scope of Miranda in a 2017 speech to the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute, and in a 2010 law review article, Coney Barrett labeled the Miranda warning extraconstitutional and an abuse of judicial power.

In four separate opinions in the 1960s, the Supreme Court interpreted the Fourth Amendment to prohibit warrantless searches and seizures and established the exclusionary rule, which prohibits the prosecution from using evidence obtained during an unlawful search.

However, as recently as 2018, Alito questioned the prohibition on warrantless searches in Collins v. Virginia. In that case, the court ruled that a police officer could not enter the defendant’s private driveway (“curtilage”) uninvited, and make a warrantless search of his tarp-covered motorcycle. Alito dissented, asserting that whether a search is unreasonable under the Fourth Amendment depends upon “the degree of intrusion on privacy.” In his view, a vehicle parked on private property is no different from a vehicle parked on a public street, despite the court’s long line of cases establishing constitutional protection from a warrantless search of a person’s curtilage.

In a concurring opinion in Collins, Thomas took direct aim at the exclusionary rule:

The exclusionary rule appears nowhere in the Constitution, postdates the founding by more than a century, and contradicts several longstanding principles of the common law … I am skeptical of this Court’s authority to impose the exclusionary rule on the States.

Three years earlier, in a 2015 interview with Bill Kristol, Alito questioned the very existence of the rule: “If you look in the Constitution, there’s nothing in the Constitution about the exclusionary rule. The Fourth Amendment says no unreasonable search and seizures, but that’s it—so where did this come from? Is it legitimate?”

In the 1932 landmark case Powell v. Alabama, the Supreme Court held that the due process clause of the 14th Amendment guarantees the right to counsel at a criminal trial.* Subsequently, the court has affirmed this right five times.

In a 2019 dissent in Garza v. Idaho, Thomas, joined by Gorsuch, asserted that a defendant’s right to state-appointed, competent counsel is not guaranteed by the Constitution:

The Sixth Amendment provides that, “in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right … to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.” That provision “as originally understood and ratified meant only that a defendant had a right to employ counsel, or to use volunteered services of counsel.” Yet, the Court has read the Constitution to require not only a right to counsel at taxpayers’ expense, but a right to effective counsel. … Because little available evidence suggests that this reading is correct as an original matter, the Court should tread carefully before extending our precedents in this area.

In Lee v. United States, Thomas challenged the definition of ineffective assistance of counsel. In that case, the court held that the failure of trial counsel to advise the defendant of possible deportation consequences when he accepted a plea agreement constituted ineffective assistance of counsel. Thomas disagreed, writing:

Under its rule, so long as a defendant alleges that his counsel omitted or misadvised him on a piece of information during the plea process that he considered of “paramount importance,” he could allege a plausible claim of ineffective assistance of counsel.

In 1982, the Supreme Court held that the press and public have a qualified First Amendment right to attend criminal trials. Two years later, in 1984, the court ruled that under the First Amendment, open public proceedings in criminal trials included questioning potential jurors (voir dire). And in 2010, the court held that the right to a public criminal trial, including jury selection, was also mandated by the Sixth Amendment.

And yet, in Weaver v. Massachusetts, a 2017 decision, Thomas not only questioned whether the right to a public trial extends to jury selection but urged the court to reconsider. In a concurring opinion, Thomas wrote:

The Court previously held … that the Sixth Amendment right to a public trial extends to jury selection. I have some doubts about whether that holding is consistent with the original understanding of the right to a public trial, and I would be open to reconsidering it in a case in which we are asked to do so.

In Taylor v. Louisiana (1975) and in Duren v. Missouri (1979), the Supreme Court upheld the requirement that under the Sixth Amendment, jurors be selected from a representative cross section of the community. In both cases, at issue were state laws that exempted women from jury service.

In 2010, Thomas invited the court to revisit the fair cross section right in the case of Berghuis v. Smith, writing in a concurring opinion:

The Court has nonetheless concluded that the Sixth Amendment guarantees a defendant the right to a jury that represents “a fair cross section” of the community. In my view, that conclusion rests less on the Sixth Amendment than on an “amalgamation of the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,” and seems difficult to square with the Sixth Amendment’s text and history. Accordingly, in an appropriate case I would be willing to reconsider our precedents articulating the “fair cross section” requirement.

In 1986, the Supreme Court ruled, in the landmark case of Batson v. Kentucky, that a state may not discriminate on the basis of race when exercising peremptory challenges against prospective jurors in a criminal trial. (Peremptory challenges allow each side in a criminal or civil case to excuse potential jurors for any reason or no reason at all, as long as they have not been removed because of their race, gender, sexual orientation, or religion.)

In 2019, after six trials, the Supreme Court reversed the murder convictions of Curtis Flowers, a Black man. Kavanaugh, who authored the opinion for the court, strongly criticized the prosecutor’s abuse of peremptory challenges against Black jurors. Thomas, in his dissent, joined by Gorsuch, would have upheld Flowers’ convictions and overturned Batson:

Much of the Court’s opinion is a paean to Batson v. Kentucky, which requires that a duly convicted criminal go free because a juror was arguably deprived of his right to serve on the jury. That rule was suspect when it was announced, and I am even less confident of it today. … The more fundamental problem is Batson itself.

“The Eighth Amendment bars not only those punishments that are ‘barbaric,’ but also those that are ‘excessive’ in relation to the crime committed, and a punishment is ‘excessive’ and unconstitutional if it (1) makes no measurable contribution to acceptable goals of punishment, and hence is nothing more than the purposeless and needless imposition of pain and suffering; or (2) is grossly out of proportion to the severity of the crime.” This was the 1977 holding of the Supreme Court in Coker v. Georgia. Since then, in 1983 and 2008, the court affirmed the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment in sentencing.

Nevertheless, Thomas, in a dissent joined by Alito, questioned this right. In Graham v. Florida (2010), Thomas took the view that a life sentence without parole in a non-homicide case does not violate the Eighth Amendment, whether imposed upon an adult or upon a juvenile. He wrote:

Although the text of the Constitution is silent regarding the permissibility of this sentencing practice, and although it would not have offended the standards that prevailed at the founding, the Court insists that the standards of American society have evolved such that the Constitution now requires its prohibition. … The Florida Legislature has concluded that such sentences should be available for persons under 18 who commit certain crimes, and the trial judge in this case decided to impose that legislatively authorized sentence here. Because a life-without-parole prison sentence is not a “cruel and unusual” method of punishment under any standard, the Eighth Amendment gives this Court no authority to reject those judgments.

Two years later, Thomas took a similarly harsh stance in the case of Miller v. Alabama, in which the court ruled that mandatory life without parole for juveniles constitutes cruel and unusual punishment, in violation of the Eighth Amendment. In his dissent, Thomas, adopting an originalist approach, asserted that only torture is prohibited by the Eighth Amendment:

As I have previously explained, “the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause was originally understood as prohibiting torturous methods of punishment—specifically methods akin to those that had been considered cruel and unusual at the time the Bill of Rights was adopted.” … Instead, the clause leaves the unavoidably moral question of who “deserves” a particular nonprohibited method of punishment to the judgment of the legislatures that authorize the penalty. … Accordingly, the idea that the mandatory imposition of an otherwise-constitutional sentence renders that sentence cruel and unusual finds no support in the text and history of the Eighth Amendment.

In 2008, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Kennedy v. Louisiana, held that the “cruel and unusual” language of the Eighth Amendment barred Louisiana from imposing the death penalty on an adult rapist of a child, where the crime did not result, and was not intended to result, in the child’s death. Alito, joined by Roberts, Scalia and Thomas, dissented:

This holding is not supported by the original meaning of the Eighth Amendment. … It is the judgment of the Louisiana lawmakers and those in an increasing number of other States that these harms justify the death penalty. The Court provides no cogent explanation why this legislative judgment should be overridden. Conclusory references to “decency,” “moderation,” “restraint,” “full progress,” and “moral judgment” are not enough.

The principles of decency, moderation, restraint, full progress, and moral judgment have been strained to the point of breaking by the current court. Be prepared for more of the same in the years ahead.