Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dies at 87

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Supreme Court justice who was as pioneering as she was brash, died on Friday, the court said. She was 87.

Despite her diminutive stature, Ginsburg was larger than life, both on and off the bench. Viewed as a feminist icon, she broke countless barriers, never shying away from making controversial comments along the way — with everything from her high court opinions to her octogenarian workout routines earning her the nickname the "Notorious R.B.G." by her rabid fan base.

Diagnosed with cancer four times, Ginsburg had had numerous health scares, including numerous recent hospitalizations.

A sharp-tongued moderate liberal, Ginsburg was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1993 and had repeatedly vowed to stay on as long as her health permitted, even when some liberals pressured her to step down at age 81 during the Obama administration so a Democratic president could be guaranteed to appoint her successor.

“Tell me who the president could have nominated this spring that you would rather see on the court than me?” was the justice's tart response at the time.

Those who faced her ire were offered no protection by political prowess or fame. She once called then-presidential candidate Donald Trump a "faker" and publicly criticized National Football League quarterback Colin Kaepernick for refusing to stand during the national anthem. She later apologized for the criticism of Trump.

Despite ruffling some feathers, Ginsburg had a fervent following, with devotees who cared about her rigorous fitness regimen almost as much as they cared about how she voted on the high court. Her likeness appeared on female empowerment T-shirts and other paraphernalia, and she was dubbed the "Notorious R.B.G." by a fan blog in 2013.

Ginsburg, who was only the second female justice to sit on the nation's highest court, was a fierce crusader for women's rights. She credited her mother, who died of cancer a day before Ginsburg graduated from high school, with influencing her advocacy for women.

"My mother told me two things constantly: One was to be a lady, and the other was to be independent. The latter was something very unusual, because for most girls growing up in the 1940s, the most important degree was not your B.A., but your 'M.R.S.,'" Ginsburg said in an appearance at Duke University in 2005.

"My mother told me two things constantly. One was to be a lady, and the other was to be independent."

Her path to the Supreme Court was laden with obstacles.

Born March 15, 1933, in Brooklyn, New York, Ruth Joan Bader graduated with a degree in government at top of her class from Cornell University in 1954, the same year she married her college sweetheart, Martin Ginsburg, who became a leading tax lawyer.

The couple moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where he was stationed with the Army Reserve. She worked for the Social Security Administration — only to be demoted after becoming pregnant with their first child, who born in 1955.

Returning East, Ginsburg enrolled in Harvard Law School in 1956 before transferring to Columbia Law School. She tied for first in her class when she received her law degree in 1959. But when she applied for jobs afterward, she discovered that most law firms didn't want her, despite her sparkling credentials.

"In the Fifties, the traditional law firms were just beginning to turn around on hiring Jews. But to be a woman, a Jew and a mother to boot — that combination was a bit too much," she once wrote.

Ginsburg eventually got a job clerking for U.S. District Judge Edmund Palmieri in Manhattan before she moved to Rutgers University, where she was a law professor from 1963 to 1972.

She became pregnant with her second child while teaching at Rutgers, and, fearing she would get fired, hid her growing stomach by wearing baggy clothes. She gave birth over summer break in 1965 and returned to work in the fall. She then taught at Columbia, where she became the university's first female tenured professor.

Ginsburg devoted herself to reversing the social norms that had made her own career so difficult.

In 1972, the Ginsburgs — Martin Ginsburg, who died from cancer in 2010 was a highly respected tax lawyer in his own right — led the legal team that successfully argued an appeal on behalf of a man who was denied a tax deduction for dependent-care expenses related to his support for his 89-year-old mother.

The 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found that the IRS regulation under which the deduction was denied was "a special discrimination premised on sex alone, which cannot stand" — a ruling that became crucial to decades of sexual discrimination jurisprudence and a central part of the 2018 movie "On the Basis of Sex," written by Andrew Stiepleman, Ginsburg's nephew.

(A biographical documentary, "RBG," also became a surprise hit in mid-2018 as Ginsburg emerged as a symbol for activists, especially women, opposed to the administration of President Donald Trump.)

Ginsburg would continue to challenge gender-based laws throughout the 1970s as a volunteer lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union, for which she also served as founder and director of the Women's Rights Project.

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. She served in that role until President Bill Clinton appointed her to the Supreme Court in 1993.

Throughout her tenure on the high court, Ginsburg remained at the forefront of gender equality law.

In 1996, she wrote the majority decision that struck down Virginia Military Institute's men-only admissions policy as violating the 14th Amendment.

"Women seeking and fit for a VMI-quality education cannot be offered anything less," Ginsburg wrote.

While she has become a heroine to many activists, she has said she didn't consider herself one of them at first.

"I did not think of myself as a feminist in the 1950s," she said in a 1988 speech. She fought for women's legal rights, she said, "for personal, selfish reasons."

And she never expected to end up on the Supreme Court. In a 1993 New York Times profile, childhood friends remembered the girl nicknamed "Kiki" Bader as the one who chipped her tooth while twirling batons for her high school football team's games.

"She was very modest, and didn't appear to be super self-confident," Ann Burkhardt Kittner, a close high school friend, told The Times. "She never thought she did well on tests, but, of course, she always aced them."

As a justice, Ginsburg voted for workers' rights and the separation of church and state. Her opinions and dissents often drew attention for their blunt but eloquent explanations of her positions.

Her strongly worded dissent in Ledbetter vs. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. in 2007 explicitly called on Congress to relax the statute of limitations on equal pay lawsuits, observing that "a worker knows immediately if she is denied a promotion or transfer. Compensation disparities, in contrast, are often hidden from sight."

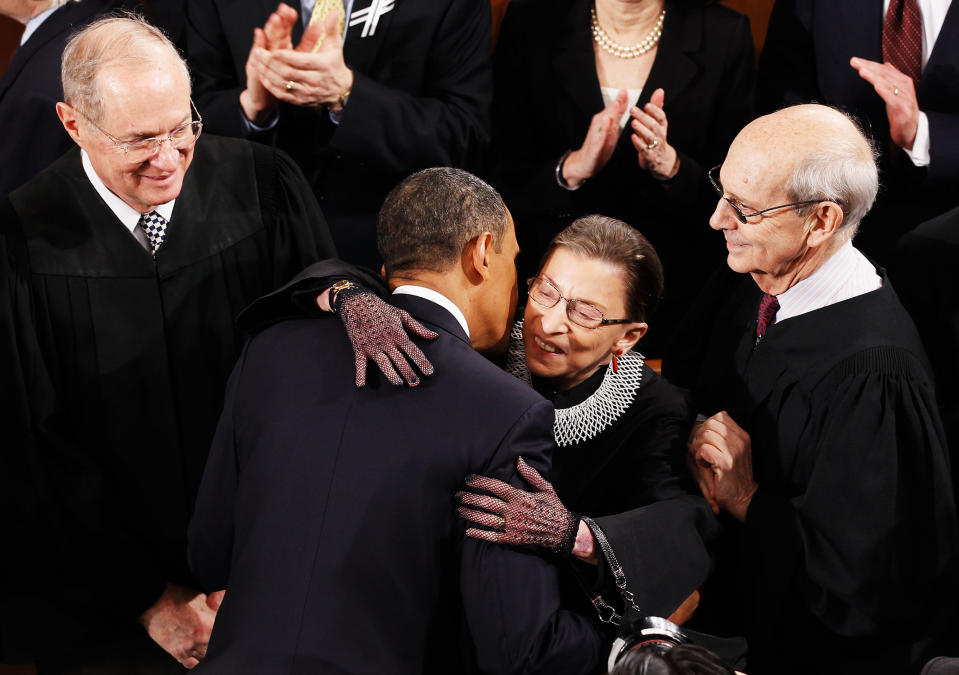

President Barack Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, named in honor of the plaintiff, in 2009.

In 2013, Ginsburg joined the majority in striking down the Defense of Marriage Act, or DOMA, ruling that same-sex couples married in states where it such weddings are legal are entitled to the same federal benefits as heterosexual couples.

In one of the case's most striking moments, Ginsburg said at oral arguments that DOMA institutionalized "two kinds of marriage: the full marriage, and then this sort of skim milk marriage."

Just a few months later, she became the first Supreme Court justice to officiate at a same-sex wedding, presiding over the marriage of her longtime friend Michael Kaiser to economist John Roberts at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, of which Kaiser was then president.

And in a searing dissent to the court's 5-to-4 Hobby Lobby contraception ruling in 2014 — which held that the government can't require certain employers to provide insurance coverage for birth control that's in conflict with their religious beliefs — she wrote: "The court, I fear, has ventured into a minefield."

Ginsburg had overcome serious health problems before: In February 2009, when she was 75, she had surgery to remove a small tumor in her pancreas. Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest cancers, spreading quickly and seldom detected early, and like many other patients, she had no symptoms. In her case, the tumor was discovered early enough to remove. In summer 2019, Ginsburg again had a brush with cancer in her pancreas, receiving radiation therapy for a malignant tumor.

She also had colon cancer in 1999, for which she received treatment, and a heart stent put in in 2014. In July 2018, Ginsburg was hospitalized after having broken three ribs; at the end of that year, she had surgery for early-stage lung cancer.

Ginsburg is survived by her children, Jane and James. While she was serious about the causes that were important to her, she also made time to have fun: In November 2016, at age 83, she had a small speaking role on the opening night of "The Daughter of the Regiment," a show at the Washington National Opera.

Asked beforehand by NPR whether she thought she would have stage fright when it came time to step out of her comfort zone as a Supreme Court justice and perform in the opera, Ginsburg just laughed.

"What's to be nervous about?" she asked.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com.