The Supreme Court’s Liberals Are Already Fed Up With This Term

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Of the many federal agencies that Republicans oppose on principle, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has the distinction of being one of the few they were complaining about before it even existed.

In the years since, conservatives have taken every imaginable angle on demeaning, defanging, or abolishing the CFPB, which Congress created as a direct response to the 2008 financial crisis. Railing against its unconscionable infringements on personal liberty and consumer choice became a staple of Republican stump speeches overnight. In 2015, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz introduced a bill to repeal the bureau, a stunt he’s repeated several times since. In a harebrained bid to hollow out an agency his party could not eliminate, President Donald Trump installed Mick Mulvaney, who as a congressman smeared the bureau as “sick,” “sad,” and a “joke,” as its chief in 2017. Per the New York Times, Mulvaney showed up for work “no more than two or three days a week, a few hours at a time.”

Republicans came closest to dismantling the bureau in 2020, when a much-hyped legal challenge to the bureau’s leadership structure, which limited the president’s ability to fire the director, made it all the way to the Supreme Court. But in a surprise ruling in Seila Law v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Chief Justice John Roberts handed the bureau a reprieve, loosening the restrictions on the president’s removal power but otherwise allowing the bureau to continue its work. Conservatives who had hoped to celebrate the public death of Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s brainchild were crushed: “By ratifying most of the bureau’s unconstitutional design, the ruling will encourage Congress to create more agencies that violate the separation of powers,” the Wall Street Journal editorial board wrote.

It is not a surprise, then, that anti-CFPB activists have wriggled their way back to the court, which is now even more conservative than it was three years ago. On Tuesday, the justices heard oral argument in Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. Community Financial Services Association of America, a case about a different purported constitutional fatal flaw in the bureau’s design: this time, the manner in which Congress funds its operations. Of course, the object this time is the same: Republican Party politicians have been fighting the very existence of this bureau for 13 years and counting. CFSA gives the Republican Party’s Supreme Court justices their latest, best chance to win that war.

The Constitution’s appropriations clause provides that “no Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” Over the past two centuries, Congress has exercised this broadly defined power in a broad array of ways. You are likely most familiar with Congress’ annual efforts to pass an appropriations bill, during which Republican lawmakers invariably use the threat of a government shutdown to drain the coffers of government agencies whose agendas they don’t like.

Hoping to protect the bureau from becoming a perennial hostage in Washington’s dumbest ritual, Congress chose to fund the bureau differently: Under the Dodd-Frank Act, the CFPB gets its money from the Federal Reserve, which is funded by interest on securities it owns and fees assessed to the institutions it oversees. The question in CFSA is whether Congress’ decision to insulate the bureau from political brinkmanship complies with the appropriations clause. The government says that an act of Congress—here, the aforementioned Dodd-Frank Act, which Congress passed in 2010—is enough. The CFSA, a group of payday lenders represented by Jones Day and backed by basically every trade association and conservative nonprofit in America, says it isn’t. But they’re unwilling to stop there: If the bureau’s funding structure is unconstitutional, they contend, then everything the bureau has done since its inception must be unconstitutional, too.

It is hard to overstate how untethered from reality this argument is. At least six federal district courts and one federal court of appeals have rejected it. The Supreme Court has previously held that compliance with the appropriations clause merely requires Congress to pass a law. When litigating this case in the court below, CFSA thought so little of this argument’s chances of success that it spent only two pages briefing it.

Unfortunately, the court below in this case is the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, a federal appeals court controlled by a gaggle of Trump appointees who are perpetually auditioning for a spot on Leonard Leo’s Supreme Court shortlist. And last year, a three-judge panel of, yes, all Trump appointees seized the opportunity, declaring that the bureau’s “perpetual insulation” from the annual appropriations process “cannot be reconciled” with the appropriations clause. This is inspiring stuff: The 5th Circuit’s respect for Congress’ power of the purse is so profound that its unelected judges have created for themselves a veto over how Congress exercises it.

This decision, if ratified by the Supreme Court, would devastate the bureau’s ongoing efforts to protect veterans, farmers, rural Americans, and people of color from the most predatory products the financial services industry can dream up. It would cast doubt on the continued viability of other similarly funded regulators, including the Federal Reserve Board, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and open the door to future challenges to Social Security, Medicare, and other vital entitlement programs. In an amicus brief, a mortgage trade group diplomatically acknowledges that it has “disagreed with some of the CFPB’s past actions,” but warns of “catastrophic” consequences for the housing market, which could “grind to a halt” if the CFSA gets its way. In other words, we do not love the CFPB, but we do not love plunging the nation into financial chaos, either.

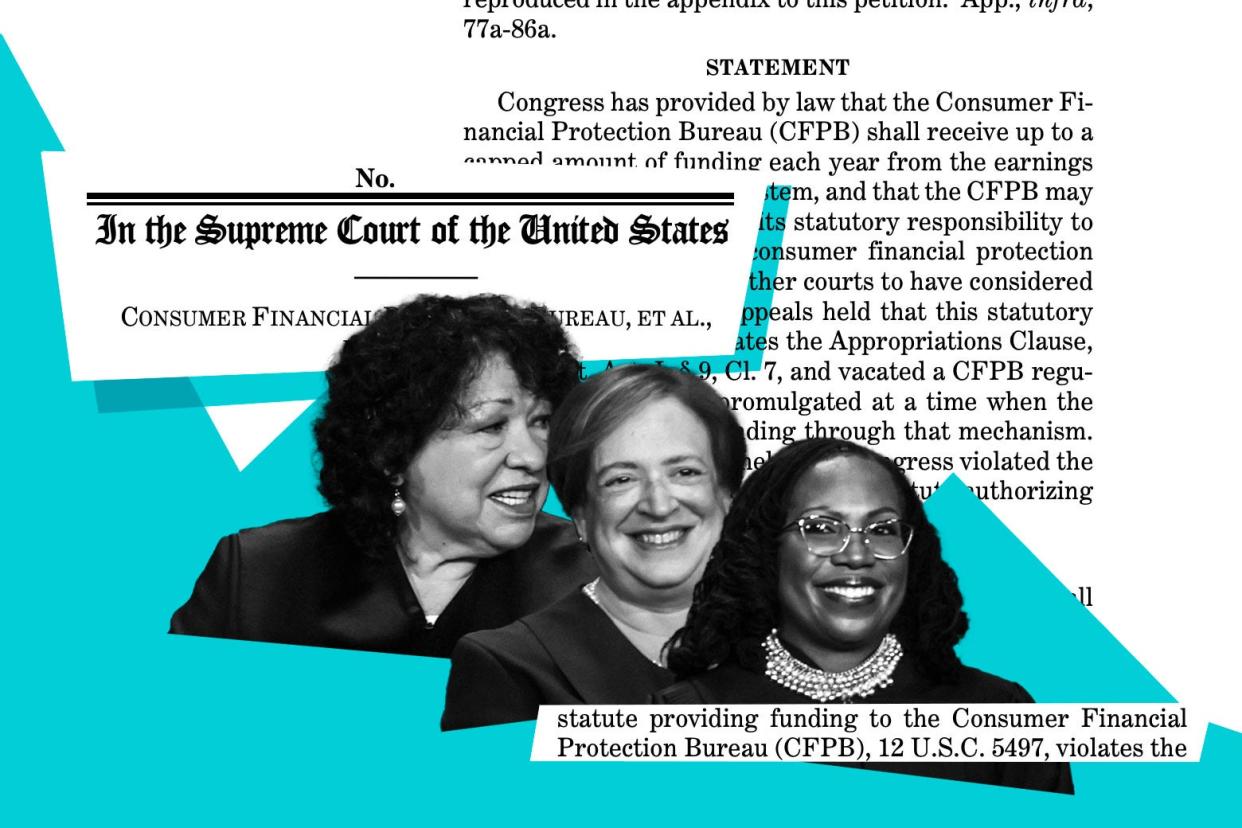

At oral argument on Tuesday, the liberal justices had quite obviously had enough of both the 5th Circuit’s fondness for playing with matches and Jones Day’s willingness to supply accelerants. Some Supreme Court cases are a battle of proposed tests, but Noel Francisco, the Trump solicitor general who argued the case for CFSA, could not even settle on one, much to the liberal justices’ frustration. Justice Sonia Sotomayor told him she was at a “total loss” in trying to understand his argument in the first place. Justice Elena Kagan variously characterized his argument as “decisively rejected by our history,” “flying in the face of 250 years of history,” and “profoundly ahistorical.” She also lightly mocked his contention that the fact that the bureau has never reached its funding cap renders the cap legally meaningless. “Maybe it’s good evidence that the CFPB should be doing more,” she said.

As she was yesterday, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was probably the court’s most vocal questioner. At times, she sounded like she was on the verge of incredulous laughter, asking Francisco how he could glean an unstated congressional obligation to fund government in fixed, time-limited increments from the single word “Appropriations,” and castigating him for manufacturing a constitutional problem by imagining a constitutional provision that does not actually exist. “We can’t just suddenly decide that things are ‘troubling’ without some kind of legal reference point,” Jackson told him.

A few conservatives appeared skeptical, too, if not as contemptuous as their liberal counterparts. (Contemplating your power to torpedo the global economy can be a sobering exercise.) Justice Amy Coney Barrett jumped in on Jackson’s line of questioning, observing that Francisco’s case lacks the “textual hook” of cases like Seila Law that deal with the president’s removal power. Justice Brett Kavanaugh sounded even more baffled at oral argument than he usually does, suggesting that a congressional appropriation that Congress could change at any time simpy by passing a new law is by definition not “perpetual,” “entrenched,” or “permanent.” These adjectives, he said, are “a little strong here.”

Ultimately, the liberals may be able to cobble together a majority to stave off a judicially induced Great Depression. But even if the bureau survives this time, for as long as the court is controlled by a conservative supermajority, conservative activists will keep cooking up deranged arguments they think can win five votes. For the liberal justices, meanwhile, holding at bay the most dangerous, least coherent silliness the 5th Circuit has to offer is the best outcome they can hope for. This burden is tremendous and thankless, and it’s only going to get heavier in the months and years ahead.