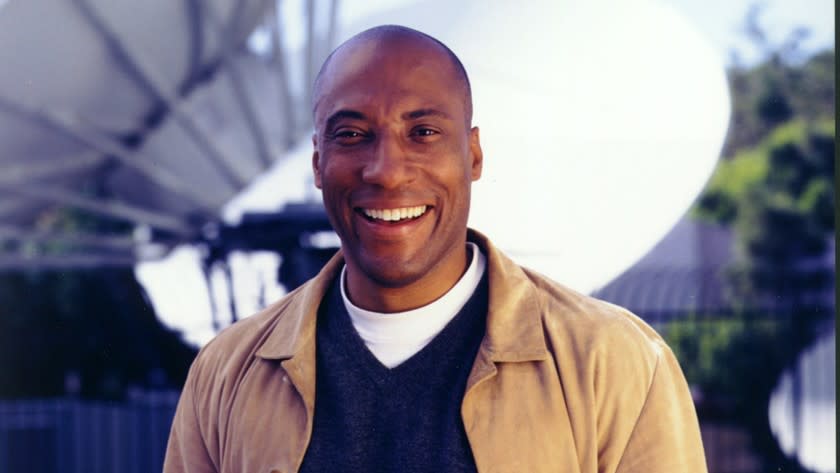

Supreme Court limits race-bias lawsuits in a setback for L.A. TV producer Byron Allen

The Supreme Court put new limits on race-bias lawsuits Monday, dealing a setback to Los Angeles TV producer Byron Allen, who maintained that Comcast refused to carry his channels on its cable network because he's black.

In a 9-0 decision, the court said it was not enough for a civil rights plaintiff to assert that his race was one of several factors that motivated a company to refuse to do business with him. Instead, he must show race was the crucial and deciding factor.

"To prevail, a plaintiff must initially plead and ultimately prove that, but for race, it would not have suffered the loss of a legally protected right," said Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, speaking for the court. He said the court had set this high bar for most other civil rights claims, and there was no reason to lower it for suits that involved contracting with large corporations.

Allen, who owns Entertainment Studios Network, had negotiated with Comcast and Charter Communications, seeking slots for seven of his channels, including Pets.TV, Cars.TV and Comedy.TV. Both companies expressed some interest but said they already carried other similar channels.

When the talks ended with no deal, Allen filed lawsuits in Los Angeles against both companies seeking billions of dollars in damages and alleging racial discrimination. He said, for example, that Comcast had given slots to lesser-known channels produced by white-owned companies. He also alleged a Comcast executive had said, "We're not trying to create any more Bob Johnsons,” referring to the African American founder of Black Entertainment Television.

For five years, judges had been split over whether Allen had enough evidence of racial bias to go forward and seek a trial. His suit was legally significant because it relied on the historic Civil Rights Act of 1866. Enacted a year after the Civil War, it decreed that blacks " shall have the same right ... to make and enforce contracts ... as is enjoyed by white citizens.”

U.S. District Judge Terry Hatter considered several amended complaints but ultimately dismissed Allen's suit because Allen did not have evidence to show that racial bias was the reason for Comcast's decision not to carry his channels.

But the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed and cleared the way for the suits against both Comcast and Charter Communications to proceed. Its judges said that if race appears to have been a motivating factor, that is sufficient for the suit to proceed.

"We can infer from the allegations ... that discriminatory intent played at least some role in Comcast’s refusal to contract with Entertainment Studios, thus denying the latter the same right to contract as a white-owned company," the 9th Circuit said. The appeals court added that plaintiffs at the early stage of a suit could not be expected to have all the evidence needed to prove their claims.

Lawyers for both Comcast and Charter appealed to the Supreme Court and argued that the 9th Circuit's looser standard would permit a wave of big lawsuits against companies.

On Monday, the high court set aside the 9th Circuit's opinion and ruled Allen and other plaintiffs must have clear evidence from the beginning that racial bias was the cause of the company's action.

But the decision in Comcast vs. National Assn. of African American Owned Media was not a total loss for Allen. The justices sent the case back to the 9th Circuit in California to consider again whether Allen had enough proof of racial bias to continue his suit.

Allen said in a statement: "Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has rendered a ruling that is harmful to the civil rights of millions of Americans. This is a very bad day for our country."

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg filed a concurring opinion that said she joined the unanimous ruling with some reluctance. She said racial bias during the contracting process should be illegal, even if it is not clear the company's final decision turned on race.

"An equal 'right ... to make ... contracts,' is an empty promise without equal opportunities to present or receive offers and negotiate over terms," she wrote. "The court holds today that Entertainment Studios must plead and prove that race was the but-for cause of its injury — in other words, that Comcast would have acted differently if Entertainment Studios were not African-American owned. But if race indeed accounts for Comcast’s conduct, Comcast should not escape liability for injuries inflicted during the contract-formation process. The court has reserved that issue for consideration on remand, enabling me to join its opinion."

Comcast issued a statement welcoming the ruling.

“We are pleased the Supreme Court unanimously restored certainty on the standard to bring and prove civil rights claims. The well-established framework that has protected civil rights for decades continues. The nation’s civil rights laws have not changed with this ruling; they remain the same as before the case was filed. We now hope that on remand the 9th Circuit will agree that the district court properly applied that standard in dismissing Mr. Allen’s case three separate times for failing to state any claim," the company said.

Kristen Clarke, president of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, said the ruling "puts in place a tougher burden of proof that will likely make it more difficult for many discrimination victims to invoke the protections of Section 1981 in discrimination cases. No doubt, this ruling may shut the courthouse door on some discrimination victims who, at the complaint stage, may simply be without the full range of evidence needed to meet the court's tougher standard," she said.