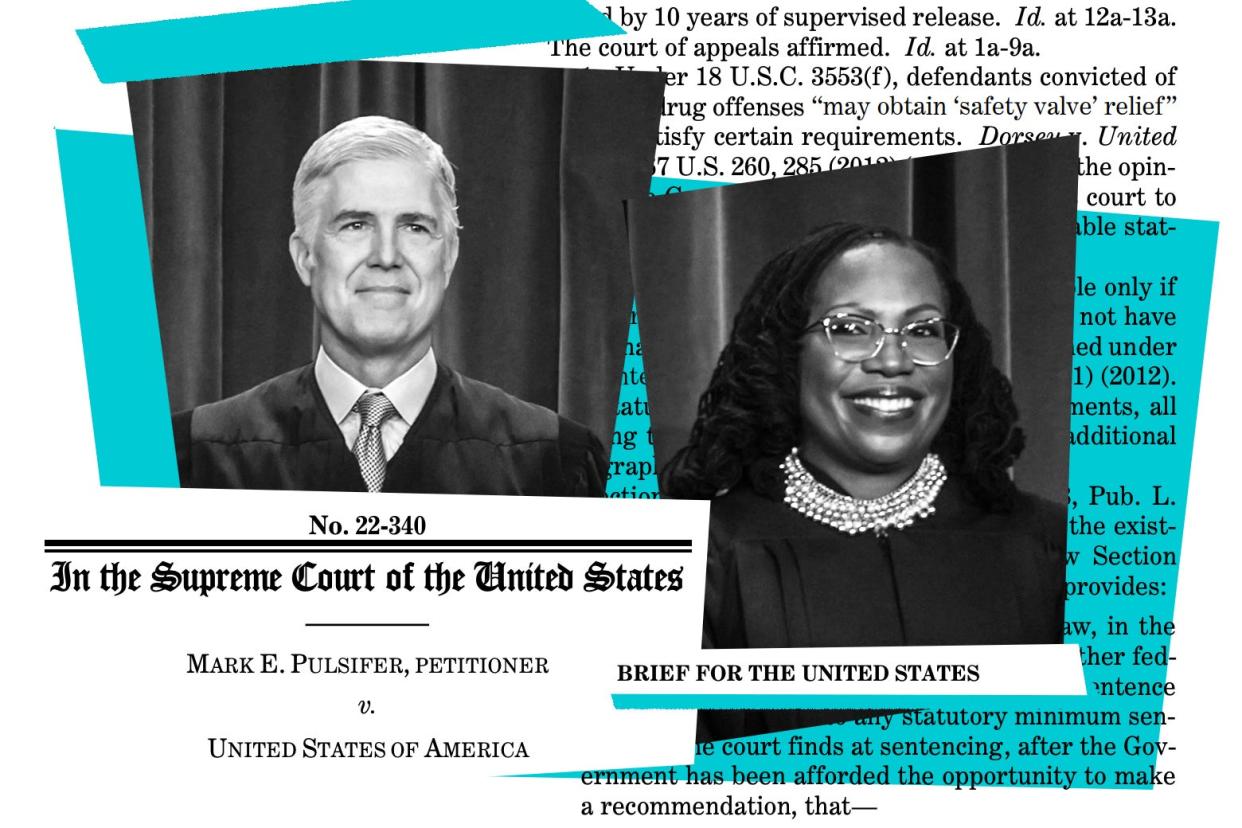

The Supreme Court’s Oddest Pairing Comes out Swinging on Behalf of Criminal Defendants

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is part of Opening Arguments, Slate’s coverage of the start of the latest Supreme Court term. We’re working to change the way the media covers the Supreme Court. Support our work when you join Slate Plus.

On Monday, the Supreme Court opened its 2023–24 term by wrestling with a question that only lawyers could spend 90-plus minutes arguing about: what the word and means.

The case, Pulsifer v. United States, began winding its way through the legal system three years ago, when Mark Pulsifer sold about a third of a pound of meth to a customer who turned out to be a confidential informant. After his arrest, Pulsifer pleaded guilty to a felony count of methamphetamine distribution. And because of his criminal record—he’d been convicted of another drug-related felony several years earlier—he was suddenly facing a mandatory minimum sentence of 180 months in federal prison.

Fortunately for Pulsifer, mandatory minimums are not exactly in vogue on Capitol Hill these days, given the mountains of evidence that they drain public resources without making anyone safer, all while exacerbating horrific racial disparities in a criminal legal system already rife with them. In 2018 Congress passed the First Step Act, a bipartisan criminal justice reform bill that, among many other things, allows judges to deviate from mandatory minimums for people convicted of nonviolent drug offenses. This provision of federal law, known as the “safety valve,” assigns point values to different offenses and defines the group of people eligible for sentencing reductions as follows: anyone who does not have a significant criminal history (4 or more total points), a prior serious offense (a 3-point offense), and a prior (2-point) violent offense.

This might sound like a lot of numbers, but here the sums matter less than the three-letter word that ties them together. Pulsifer has more than 4 total points, and a previous 3-point conviction. However, he’s never been convicted of a 2-point violent offense. Thus, he says, the safety valve covers him: People aren’t eligible for sentencing relief only if they meet all three criteria, A, B, and C. And because Pulsifer doesn’t meet criterion C, he should be eligible for a sentencing reduction of about five years. Or, as his lawyers put it in their brief, the law’s “plain meaning is unambiguous: “ ‘and’ means ‘and.’ ”

Federal prosecutors, it will shock you to learn, feel differently: In the government’s view, anyone who fails to clear any of these hurdles is ineligible for relief. In other words, it argues that and means “or.”

At oral argument, the justices spent most of their time parsing this slurry of semicolons, em dashes, and conjunctions in painstaking detail, trying to divine whether the First Step Act uses and to join three eligibility criteria together (as Pulsifer argues) or distributively across three independently disqualifying criteria (as the government argues). The lawyers invoked an array of dictionaries, grammar usage guides, statutory drafting manuals, and handbooks for reading law, one of which was co-authored by the late Justice Antonin Scalia. Assistant to the Solicitor General Frederick Liu had the misfortune of having to explain the government’s appeal to “common sense,” which did not appear to land with members of the target audience. “I don’t know that canon, but I guess it’s a good one,” said Neil Gorsuch, the justice perhaps most obsessed with defining himself as a textualist.

By late morning, the justices seemed understandably exhausted. Clarence Thomas, frustrated by the absence of even a workable framework for trying to answer the question, analogized the debate to his least favorite concept in constitutional jurisprudence: “a substantive due process of the word and, that we just make it up as we go along,” he said. Justice Samuel Alito wondered out loud if the debate’s existence might be evidence that his beloved textualism has a dark side after all. “People who haven’t studied the case must think this is gibberish,” he said. “It might as well be Greek.”

The most interesting exchanges occurred when the justices found ways to wade through linguistic minutiae to talk about the real-world stakes of the case: years of Mark Pulsifer’s life, and of the lives of thousands of others who could spend less time in federal prison depending on how the justices decide it. The point of the First Step Act, after all, was to subject fewer people to harsh mandatory minimum sentences. Against this backdrop, why, asked Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, should the Supreme Court construe a purported ambiguity as narrowly as possible? “I appreciate that and can sometimes mean or,” she said. “But this is not a conversation. This is a statute. And it’s a criminal statute with huge implications for the lives and well-being of the people who come through the system.”

Jackson and her colleagues also returned several times to the fact that safety valve relief is not automatic—that however the justices decide this particular question, a defendant must meet several other eligibility criteria and convince a judge of their worthiness for discretionary relief to actually get a shorter sentence. In practice, ruling for Pulsifer would only marginally reduce the tremendous power that life-tenured judges wield over the futures of the people who come before them. To the extent that Congress wanted to deny anyone the opportunity to even participate in this process, Jackson pointed out, denying it only to those with the most serious and violent criminal histories doesn’t seem “crazy.”

Her most vocal ally on Monday was Gorsuch, whose occasional libertarian sympathies make him probably the most defendant-friendly justice on the conservative wing. (His reputation in this space is cartoonishly overblown in certain circles, but again, we are grading the Supreme Court’s reactionary law-and-order cruelty on a Clarence Thomas curve here.) In an exchange with Liu, Gorsuch focused on the imbalance of power between Pulsifer and the massive carceral state working diligently to lock him up for as long as possible. “The government of the United States has a lot of resources, and the average criminal defendant doesn’t,” he said. If that government is incapable of crafting coherent rules for whom and when and how to punish, it shouldn’t get the benefit of the doubt when someone points that out.

“At the end of the day, what we’re really talking about here is whether mandatory minimums send people away for … life sentences, effectively, for many people, or whether the guidelines, which are not exactly the most defendant-friendly form of sentencing known to man themselves, apply,” Gorsuch said. To that, Pulsifer’s attorney responded, gratefully: “That summation was better than my introduction.”

The court’s resolution of Pulsifer will do more than crown a winner in this battle of semantics. Future Congresses will almost certainly take up criminal justice reform again because the layered failures of mass incarceration are one of the few subjects in Washington around which there exist some bipartisan consensus. (Notably, the conservative Americans for Prosperity Foundation took a break from stumping for tax breaks for the ultrarich to file an amicus brief on Pulsifer’s behalf, arguing that “extra years of warehousing him in a prison at taxpayer expense would seem to serve little, if any, societal purpose.”) And the First Step Act, for all the fawning press it earned, was a modest reform bill that many activists who sympathized with its aspirations nonetheless criticized as insufficiently robust. As my Balls and Strikes colleague Madiba Dennie wrote recently, it is difficult enough to marshal the necessary support for meaningful criminal justice reform without a federal judiciary that reads every reform that does manage to pass as uncharitably as possible.

In a perfect world, this country’s legal system would run according to a set of concise, lucid rules that mesh seamlessly with one another. Unfortunately, the institution in charge of writing these rules is the United States Congress, which means that even well-intended reforms are invariably going to contain vexing screw-ups that entail significant consequences. In Pulsifer, the court has a choice about what role it will play in this messy process: It can either give effect to Congress’s intent or be—sorry for the legal jargon—a pedantic pain in the ass. These days, the justices play the latter role enough as it is. They don’t need any more practice.