Supreme Court Upholds Native Adoption Law In Huge Win For Tribal Sovereignty

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In a surprising 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act against challenges that could have gutted tribal sovereignty and led to the adoption of Native children into non-Native homes.

The opinion by Justice Amy Coney Barrett in the case of Haaland v. Brackeen rejected all constitutional challenges brought by both foster and birth parents and the states of Texas, Louisiana and Indiana against the law.

“The bottom line is that we reject all of petitioners’ challenges to the statute, some on the merits and others for lack of standing,” Barrett wrote.

The Protect ICWA Campaign, a coalition of groups seeking to protect the law, praised the ruling in a statement.

“We are overcome with joy that the Supreme Court has upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), which is widely regarded as the gold standard of child welfare,” wrote the campaign, which is made up of the National Indian Child Welfare Association, the National Congress of American Indians, the Native American Rights Fund and the Association on American Indian Affairs.

“The positive impact of today’s decision will be felt across generations,” the statement added.

Joining Barrett’s decision were Justices John Roberts, Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Ketanji Brown Jackson. Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas filed separate dissenting opinions, while Gorsuch and Kavanaugh filed separate concurrences. Sotomayor and Jackson joined parts of Gorsuch’s concurrence that detailed the history of lengthy and ongoing mistreatment of Native tribes by the U.S. government.

The case involved a challenge brought by foster parents, a birth mother and the state of Texas to the federal law that governs the adoption of Native children who have been placed into the child welfare system. That law prioritizes the placement of Native children into Native homes, and is seen as a keystone of respecting tribal sovereignty and remedying the historic injustices committed by the U.S. government in separating Native children from their families.

“The Indian Child Welfare Act did not emerge from a vacuum,” Gorsuch wrote in his concurring opinion. But rather as “a direct response to the mass removal of Indian children from their families” in the mid-20th century, which was in turn “only the latest iteration of a much older policy of removing Indian children from their families.”

The Supreme Court rejected a challenge to the federal law that gives preference to Native American families in foster care and adoption proceedings of Native children.

“In all its many forms, the dissolution of the Indian family has had devastating effects on children and parents alike,” Gorsuch wrote.

Plaintiffs included four non-Native families who had endeavored to adopt Native children, with varying outcomes.

The challengers sought to invalidate ICWA on numerous constitutional grounds, including that it went beyond the federal government’s authority, infringed on state sovereignty and violated the Constitution’s equal protection clause by discriminating on racial grounds against white and other non-Native foster and adoptive parents. Barrett’s decision rejected each claim, although on varying grounds.

The arguments made by the challengers, that ICWA exceeded the power of Congress by interfering in family law governing domestic relations that has been traditionally set by the states, may be at times “rhetorically powerful,” but, Barrett writes, “their arguments fail to grapple with our precedent.”

“If there are arguments that ICWA exceeds Congress’s authority as our precedent stands today, petitioners do not make them,” Barrett writes.

The decision rejects the argument that ICWA improperly commandeers state power for the federal government by noting that the law’s provisions governing the placement of children apply to both state and private actors equally.

“When a federal statute applies on its face to both private and state actors, a commandeering argument is a heavy lift — and petitioners have not pulled it off,” Barrett writes. “Both state and private actors initiate involuntary proceedings.”

In the key claims that ICWA violates the equal protection clause and that it improperly delegates authority to executive branch agencies, Barrett denied that the challengers have standing to sue.

“Article III [of the Constitution] requires a plaintiff to show that she has suffered an injury in fact that is ‘“fairly traceable to the defendant’s allegedly unlawful conduct and likely to be redressed by the requested relief,”’” Barrett wrote, citing prior court precedent. “Neither the individual petitioners nor Texas can pass that test.”

In a brief concurring opinion, Kavanaugh said that he wished to “emphasize” that lack of standing described by Barrett means the equal protection issue has been left undecided. He cast doubt on whether “the child’s race,” in this case Native heritage, can be used in determining foster placement.

In a lengthy dissent, Thomas argued that Congress lacked the authority to enact ICWA in the first place, a point that Alito agreed with, albeit in a shorter dissenting opinion. Thomas also pointed out that the high court left open the possibility of limiting the scope of the law, or striking it down, in the future.

Congress passed ICWA in 1978 to try to remedy the ugly period in American history described by Gorsuch: For decades, the U.S. government took tens of thousands of Native children away from their families on reservations, sometimes forcibly, and put them in boarding schools or placed them with white families to assimilate them into white culture.

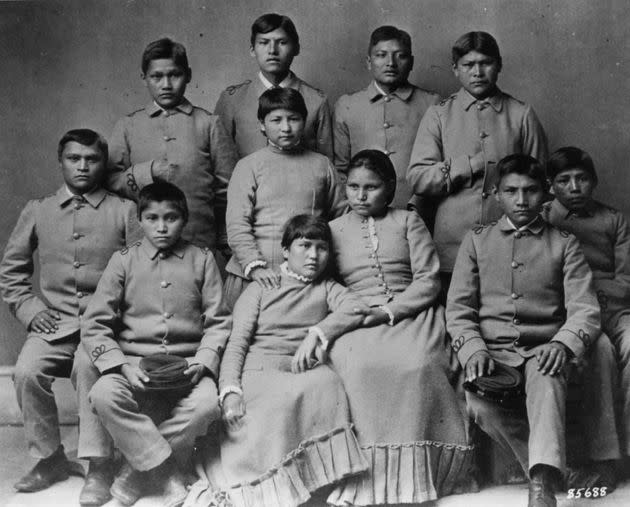

A group of Chiricahua Apaches attending Carlisle Indian School in 1886. Tribal schools like Carlisle were part of a long history of U.S. efforts to destroy Native tribes.

These children were punished for speaking their native tongue and stripped of their traditional clothing. Their hair was cut. They suffered physical, sexual and cultural abuse. Some never returned home. Surveys in 1969 and again in 1974 found that between 25% and 35% of all Native children had been separated from their families.

The intent, as Brig. Gen. Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, put it in 1892, was to “kill the Indian … and save the man.”

These “darker designs” of the federal government that aimed at “destroying tribal identity and assimilating Indians into broader society” and the effect they continue to have are the subject of Gorsuch’s concurrence.

They have “presented an existential threat to the continued vitality of Tribes — something many federal and state officials over the years saw as a feature, not as a flaw. This is the story of ICWA,” Gorsuch wrote.

ICWA has since helped rebuild Native communities and become “a model for the child welfare policies that are best practices generally,” according to 31 national child welfare groups who filed a brief in the case in 2019.

President Joe Biden said the court’s decision preserves “a vital protection” for tribal sovereignty and Native children.

“I stand alongside Tribal Nations as they celebrate today’s Supreme Court decision,” Biden said in a statement. “This lawsuit sought to undermine the Indian Child Welfare Act ― a vital law I was proud to support. The Indian Child Welfare Act was passed to protect the future of Tribal Nations and promote the best interests of Native children, and it does just that.”

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, whose own grandparents were forcibly taken from their families as children and put into federal Indian boarding schools, said Thursday’s decision is “a welcome affirmation across Indian Country” that ICWA is vital for protecting Native children and families.

Congress passed ICWA to put an end to policies that “were a targeted attack on the existence of Tribes, and they inflicted trauma on children, families and communities that people continue to feel today,” Haaland said in a statement. “The Act ensured that the United States’ new policy would be to meet its legal and moral obligation to protect Indian children and families, and safeguard the future of Indian Tribes.”

Tribal leaders nationwide similarly hailed the court’s decision as a major victory for Native tribes, children and the future of Indigenous culture and heritage.

The court’s decision is “a broad affirmation of the rule of law, and of the basic constitutional principles surrounding relationships between Congress and tribal nations,” said Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr., Morongo Band of Mission Indians Chairman Charles Martin, Oneida Nation Chairman Tehassi Hill and Quinault Indian Nation President Guy Capoeman in a joint statement.

The tribes added: “We hope this decision will lay to rest the political attacks aimed at diminishing tribal sovereignty and creating instability throughout Indian law that have persisted for too long.”