Surfside building department was under fire before tower collapsed, records show

In the years leading up to the collapse of a residential condo building in Surfside, the town’s Building Department was plagued by disorganization and lack of communication — so much so that former town manager Guillermo Olmedillo placed the department under administrative review, according to a January 2019 memorandum obtained by the Miami Herald.

The memo, which included a bullet-pointed list of action items, was addressed to former building department director Ross Prieto, who recently made headlines for his failure to raise alarms in late 2018 about “major structural damage” in the Champlain Towers South condo that partially collapsed last Thursday, killing at least 18 and leaving more than 140 missing as of Wednesday.

All inspectors needed to be immediately reachable, the town manager wrote. Prieto was to deliver a weekly schedule of all building inspections, as well as the results of all inspections, to the manager by noon each Friday. All complaints about permitting or inspection needed to be reported immediately. And all future administrative decisions were to be routed through the town manager’s office.

“Building department functions … present several challenges to all municipalities, given the fact that all applicants demand immediate response to their needs,” Olmedillo wrote. “It is essential that our Building Department delivers prompt and reliable service in those areas.”

Olmedillo said he didn’t recall formally placing any other departments under administrative review during his five-plus years as Surfside’s manager.

Prieto did not immediately respond to the Herald’s request for comment.

Olmedillo’s memo was delivered just one day after Prieto seemed to brush off a request from a condo board member at Champlain Towers South, which raised concerns about an 18-story building known as Eighty Seven Park that was being constructed next door in Miami Beach.

Mara Chouela, a board member, told Prieto in an email that workers were “digging too close to our property and we have concerns regarding the structure of our building.” She asked if a town official could come by to check.

“There is nothing for me to check,” Prieto responded 28 minutes later. “The best course of action is to have someone monitor the fence, pool and adjacent areas for damage or hire a consultant to monitor these areas as they are the closest to the construction.”

After Prieto declined to stop by or intervene with Miami Beach, Choula emailed back: “OK, thank you for your email! We thought since they are very close to the city limits that the city could [do] something.....Thank you again for all your support.”

Olmedillo said Wednesday that the response was technically valid — the work was being done in another municipality — but that perhaps Prieto could have taken a different approach.

“Perhaps a courtesy from the building official would have been, ‘Let me go and check,’ ” or to call the building official in Miami Beach to discuss it, Olmedillo said.

He said he wasn’t aware of any particular complaints regarding Prieto’s response to Chouela and chalked up the timing one day before his critical memo to a coincidence.

There is no clear indication that the Eighty Seven Park construction ultimately contributed to the Champlain Towers South collapse, although it is one of several potential contributing factors being floated by residents. Some residents complained of shaking in the building while the neighboring project was being built.

The project took place south of the Champlain Towers South building; the north side is what would later crumble.

Manager wanted county to run building department

Olmedillo, a former director of planning and zoning for Miami-Dade County, said he advocated for the town to outsource its entire building department to the county.

Almost all of Surfside’s permit and inspection records were on paper, meaning the process was slow and lacked transparency, he said. And without records readily accessible, it was easier for residents to lodge complaints and accuse building officials of cutting corners.

The county’s records, on the other hand, were entirely online.

“Building departments are always the focus of possible problems,” Olmedillo said. “The best way to dispel that is to have an open window. No hanky-panky is possible.”

Olmedillo said he spoke to a Miami-Dade County deputy mayor, Jack Osterholt, who was receptive to the idea.

“I said, ‘Could we have a [memorandum of understanding] with you guys, you take over the building department functions?’ He said he thought it was doable,” Olmedillo said.

While small cities often contract with Miami-Dade to provide fire, police and library services, the county doesn’t handle any building inspection or recertification services for municipalities, said Jaime Gascon, Code Administration director for Miami-Dade. Each city must have a building official to oversee its code.

But municipalities can hire building officials on a contract basis, Olmedillo said, and the county has filled that role before — including for some cities that had recently incorporated and were getting their operations off the ground.

“Guillermo’s idea was that the county is a well-run operation,” said Town Commissioner Eliana Salzhauer. “Rather than reinventing the wheel, let’s figure out a deal with them to handle our building department. It [would have] solved the issue of digitizing, paperwork, and personnel being maybe not fast enough.”

The town was growing, Salzhauer said, with major projects like the Grand Beach Hotel and Surf Club Residences, and it began marketing itself to tourists as the “uptown beach town.” But Salzhauer said the government, including the building department, still had a small-town feel.

“The building department was still run in a very archaic manner,” she said.

One former town official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said Olmedillo’s January 2019 memo “was like the last resort before possibly outsourcing to the county.”

“[Prieto] ran his department really autonomously,” the official said. “It was accepted as long as the work was getting done. When things weren’t getting done, that’s when it started pushing the envelope.”

Digitizing records was one task that hadn’t gotten done quickly. Town officials had talked about that goal as early as 2014, meeting records show, and the process is still ongoing today.

Nonetheless, the plan to outsource to the county fizzled as other items took priority, Olmedillo said.

His January 2019 memo came two months after Prieto had reviewed a copy of an engineer’s report that noted a “major error” in the design of the Champlain Towers South pool deck and resulting concrete damage that would get “exponentially” worse if not addressed promptly.

Prieto attended a meeting of the condo board and assured residents the building was “in very good shape,” according to meeting minutes. He emailed Olmedillo the next morning to report that it “went very well,” and that “the response was very positive from everyone in the room.”

Olmedillo said last week that he didn’t recall the exchange.

He wasn’t directly critical of Prieto in an interview, saying that while the town got lots of complaints about building permits — and that those were often routed through the manager’s office — he was never aware of complaints that suggested residents were in danger.

“To me, it was about efficiency and transparency,” Olmedillo said.

The memo announcing an administrative review of the building department was the only evidence of any discontent with Prieto’s performance in his personnel file, which shows Prieto started at $110,000 and received frequent merit raises over his seven-year tenure.

In December 2014, Prieto, who holds a master’s degree in Construction Management from Florida International University, was recognized in the town newsletter for “exceptional service.”

In the lone performance review included in his Surfside personnel file — from 2014 — then-town manager Michael Crotty praised him for “a take charge attitude within his department” and “a team player approach among the town’s management team.” Crotty had hired Prieto the year before.

The job description for director of the Surfside building department at the time of Prieto’s hiring included “technical supervisory work enforcing building inspections and plan review to ensure compliance with existing codes, ordinances and statutes.” In particular, the description said a candidate should have the “skill to correct defects in building constructions and code violations.”

Prior to taking the job in Surfside, Prieto’s personnel file shows he worked as a project manager for RRP Construction Company, a Structural Building and Roofing inspector for the City of Hialeah, an adviser for the Related Group during its work on a 55-story high rise at 50 Biscayne and a senior building inspector for Miami Beach.

Prieto resigned from his position in Surfside last October, later taking a position with C.A.P., a company that provides building department services to municipalities. Prieto worked with Doral, one of the county’s fastest growing cities.

In an email to his Surfside colleagues, Prieto announced his resignation with “a semi-heavy heart.”

“It was a good seven and half year run,” Prieto wrote. “I love most of you and I’ll miss some of you.”

Following the collapse at Champlain Towers, Prieto went on leave from his post in Doral. It was not clear whether the leave was voluntary.

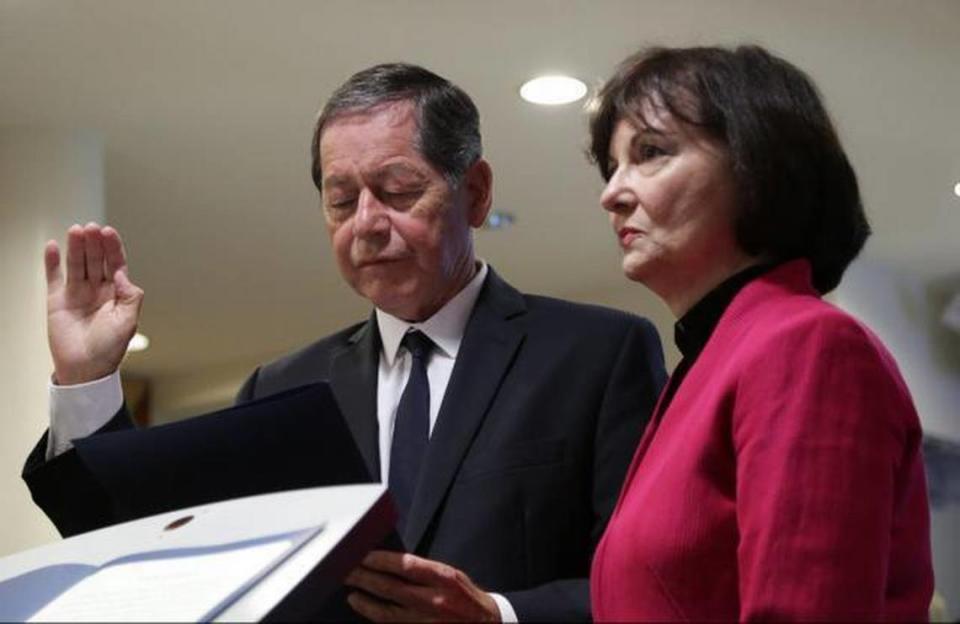

A new Surfside building official, James McGuinness, was selected in February.