The surprising Indiana origins of the Pentagon, Empire State Building and more landmarks

The Empire State Building, the Pentagon and the National Cathedral all have something in common – beyond their national, if not global, recognition. They all have special ties to Indiana.

All three buildings, as well as dozens of other significant structures around the country, were constructed with Bedford Limestone, otherwise known as Indiana Limestone. Indiana designated limestone as the official state stone in 1971, and Bedford – about 25 miles south of Bloomington – has been dubbed the Limestone Capital of the World.

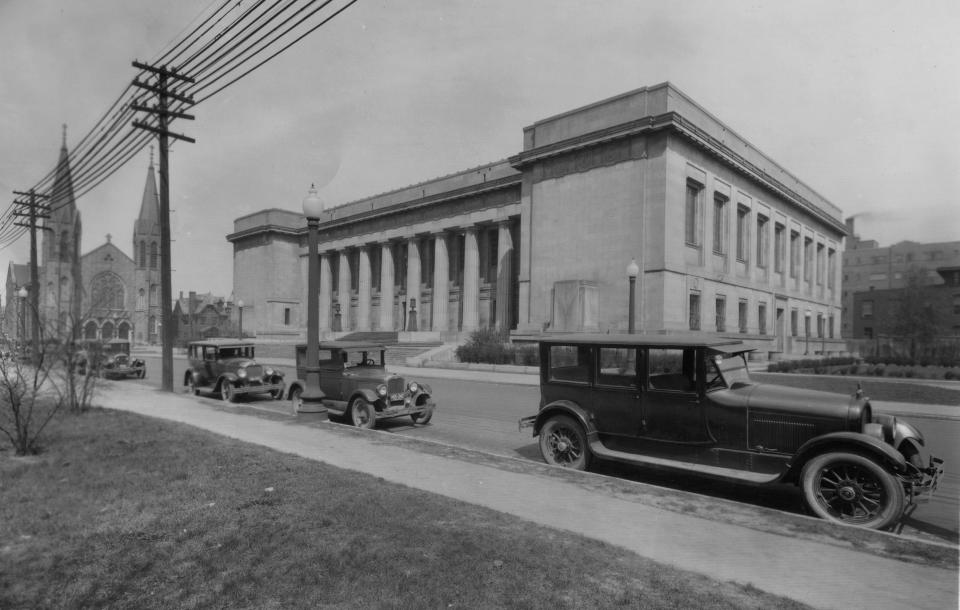

Quarrying of Indiana limestone first began nearly two centuries ago with the opening of the Richard Gilbert Quarry in 1827. At first, the quarried stone was used only locally. Many of Indiana’s official buildings are all examples of Indiana architecture made with the local limestone: the State capitol, the monuments in downtown Indianapolis, the state Government Center, and most of the 92 county courthouses. That’s not all, the majority of Indiana University’s Bloomington campus was constructed out of the stone.

But the expansion of the railroads in the 1850’s brought great need for limestone to build bridges and tunnels, and Indiana was the place to get it.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Indiana limestone represented nearly 80% of the total U.S. industry. Hoosier quarries yielded 12 million cubic feet of usable stone by 1929.

The most famous of Indiana’s quarries is the Empire Quarry, which provided nearly 19,000 tons of limestone used in constructing the Empire State Building. This quarry – which is no longer active and now is filled with water – is so long and deep that the behemoth building could fit in it.

Indiana’s limestone also can be found in the Pentagon and National Cathedral, as previously mentioned, as well as the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, parts of the Lincoln and Jefferson memorial in Washington D.C., the University of Texas clock tower and nearly three dozen state capitol buildings across the country.

There’s a reason Bedford limestone was so popular. It’s chemically pure and consistent, according to research, being composed of at least 97% calcite. That makes it more durable and stronger than most man-made products, it can be cut into very large blocks and also hold fine detail when carved.

Indiana’s limestone formed about 300 million years ago. During that time, Indiana was covered by a shallow ocean that flourished with marine life. The calcium carbonate in the shells and skeletons of corals, starfish and other creatures were then left behind and formed into thick deposits of limestone.

Despite being the backbone for many of Indiana’s and the country’s most historic buildings, stone masonry fell out of favor in the second half of the 20th century. Preferences instead shifted to buildings constructed of metal and glass.

While Indiana’s limestone is not what it once was, it still is around today. There currently are several active quarries in the state that produce more than 2 million cubic feet of limestone each year – most quarries lie between the cities of Bloomington and Bedford.

Call IndyStar reporter Sarah Bowman at 317-444-6129 or email at sarah.bowman@indystar.com. Follow her on Twitter and Facebook: @IndyStarSarah. Connect with IndyStar’s environmental reporters: Join The Scrub on Facebook.

IndyStar's environmental reporting project is made possible through the generous support of the nonprofit Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Indiana limestone used to build U.S. landmarks