The Surprisingly Progressive Promises of General Order No. 3, Which Ended Slavery in Texas

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

People take pictures next to a mural depicting the signing of General Order No. 3 during a Juneteenth celebration in Galveston, Texas, on June 19, 2021. Credit - Mark Felix–AFP/Getty Images

This year, as the nation celebrates Juneteenth as the newest federal holiday, many Black Americans will be taking part in a long-honored tradition—public readings of General Order No. 3.

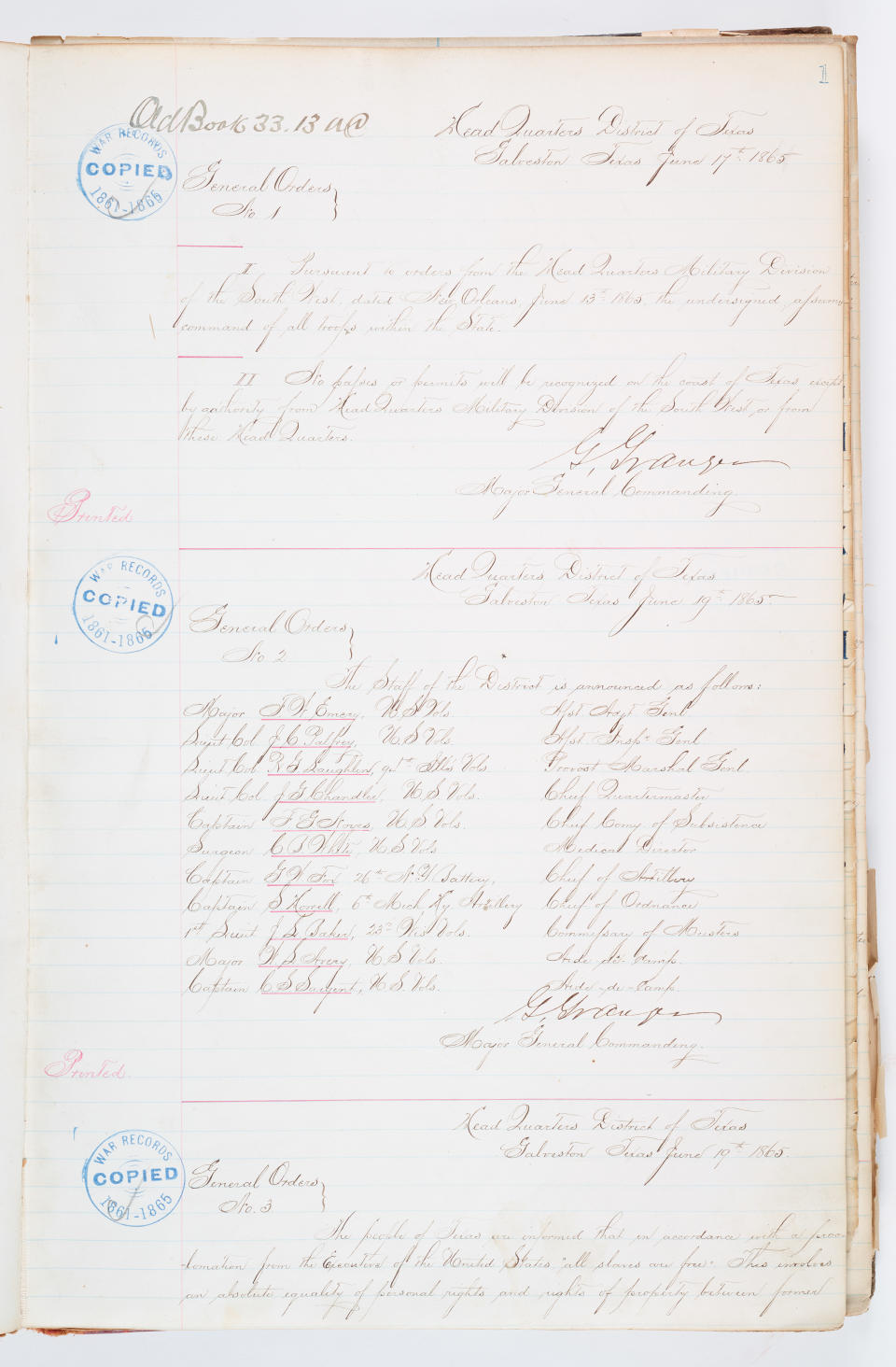

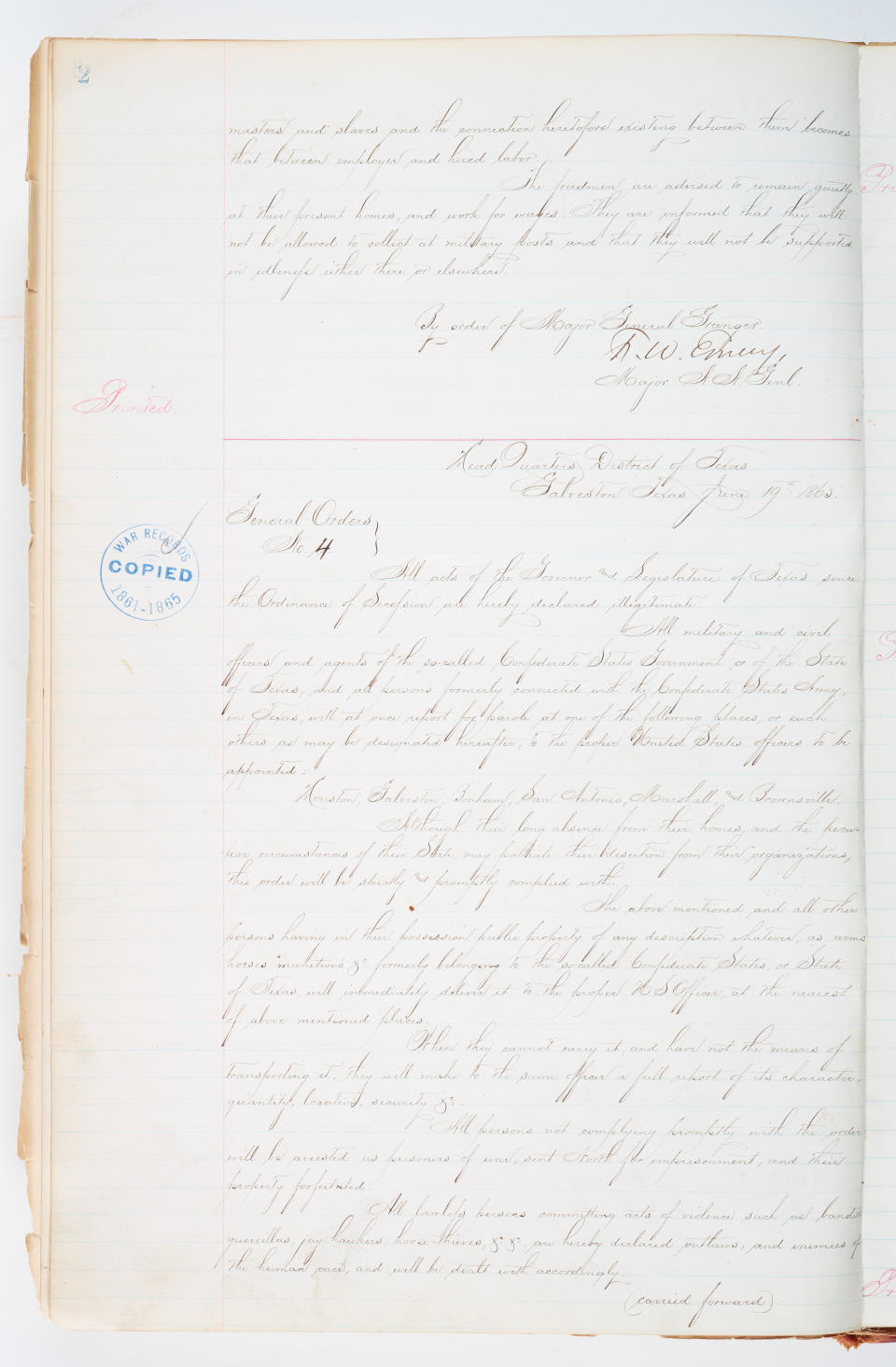

The order, issued by Union Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger on June 19, 1865 in Galveston, Texas, informed enslaved Texans of their freedom. It has been long overlooked in contemporary history, but the language was more progressive than the Emancipation Proclamation that preceded it or the 13th Amendment that followed. It promised formerly enslaved people “absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves,” and clarified the relationship between slaveholders and enslaved as one “between employer and hired labor.”

“Of the three, it is by far the most progressive. The Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment don’t mention anything about absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property,” says Greg Carr, an associate professor of Afro-American Studies at Howard University who specializes in African-American nationalism.

Here is the full text of General Order No. 3.

By the time Granger arrived in Galveston with more than 2,000 troops to enforce the end of slavery in Texas, two and a half years has passed since President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, and two months had passed since Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered. But in Texas, the war was far from settled.

“The main significance of Texas in this history is that it was relatively remote when considering the modes of transportation and communication in nineteenth-century America,” Damani Davis, an archivist at the National Archives, which has the original, handwritten text of the order signed by Maj. F.W. Emery, on behalf of Granger, tells TIME via email. This left troops vastly unequipped to tackle the territory’s sprawling landscape. “[With] 2,000 or 200,000 troops, they couldn’t police the state of Texas,” says Carr. “Though the Union had declared victory, they didn’t have the muscle to make them let them go.”

The language of Order No. 3 also promised a lot that couldn’t be delivered, advising freedmen to “remain quietly at their present homes” and “work for wages” without any way to guarantee either. “The rhetoric was, ‘We’re going to defend you,’ ‘We’re going to protect your rights to make and enforce contracts.’” says Carr. “What property did they have? Who was going to enforce the contracts?”

Indeed, compromises and unfulfilled promises that followed General Order No. 3 foreshadowed the inequality and the fight for justice that Texas, and the whole nation, are still wrestling with, Carr says.

“This has its roots in tolerating that type of hatred,” he says. “Texas has never been a white state in the way that the New England states were. And the only way Texas could be governable was to exert political and economic violence. That Juneteenth moment, in many ways, is the linchpin for putting together the pieces of the puzzle that becomes the United States of America that we live in today.”