He survived 6 days trapped on a ledge in a Utah canyon after his brother fell to his death

NASHVILLE – David Cicotello watched as the rope from which his brother rappelled whipped through the climbing anchor and fell out of sight.

Then he panicked.

"Louis!" David screamed his brother's name.

"Louis! Louis! Louis!"

Silence.

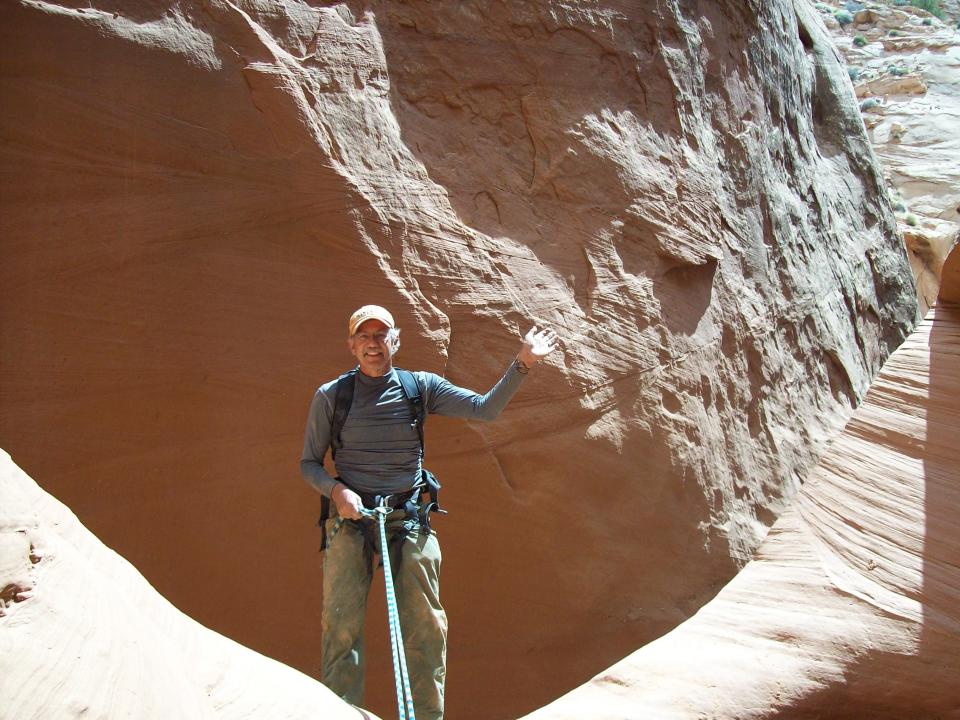

On a ledge in No Mans Canyon, tucked among Utah's masterpiece of burnt orange sandstone caverns, David paced like a caged animal searching for escape.

He looked up. It was 40 feet back to the top of the rappel – toward help.

The rock face was steep and devastatingly smooth. There were no cracks to cram his fingers into, no jibs on which to balance the toe of his hiking boot. He tried to scramble up. Tried to get his flesh to stick to rock.

He slipped, over and over again.

Then he looked down. It was 100 feet to the bottom of the canyon – the direction his brother had fallen. David had no rope. Louis was dying, or dead, below.

"Louis," he cried again, his voice hoarse and thin as he howled.

Devastated, David crumbled to the ground and he wept.

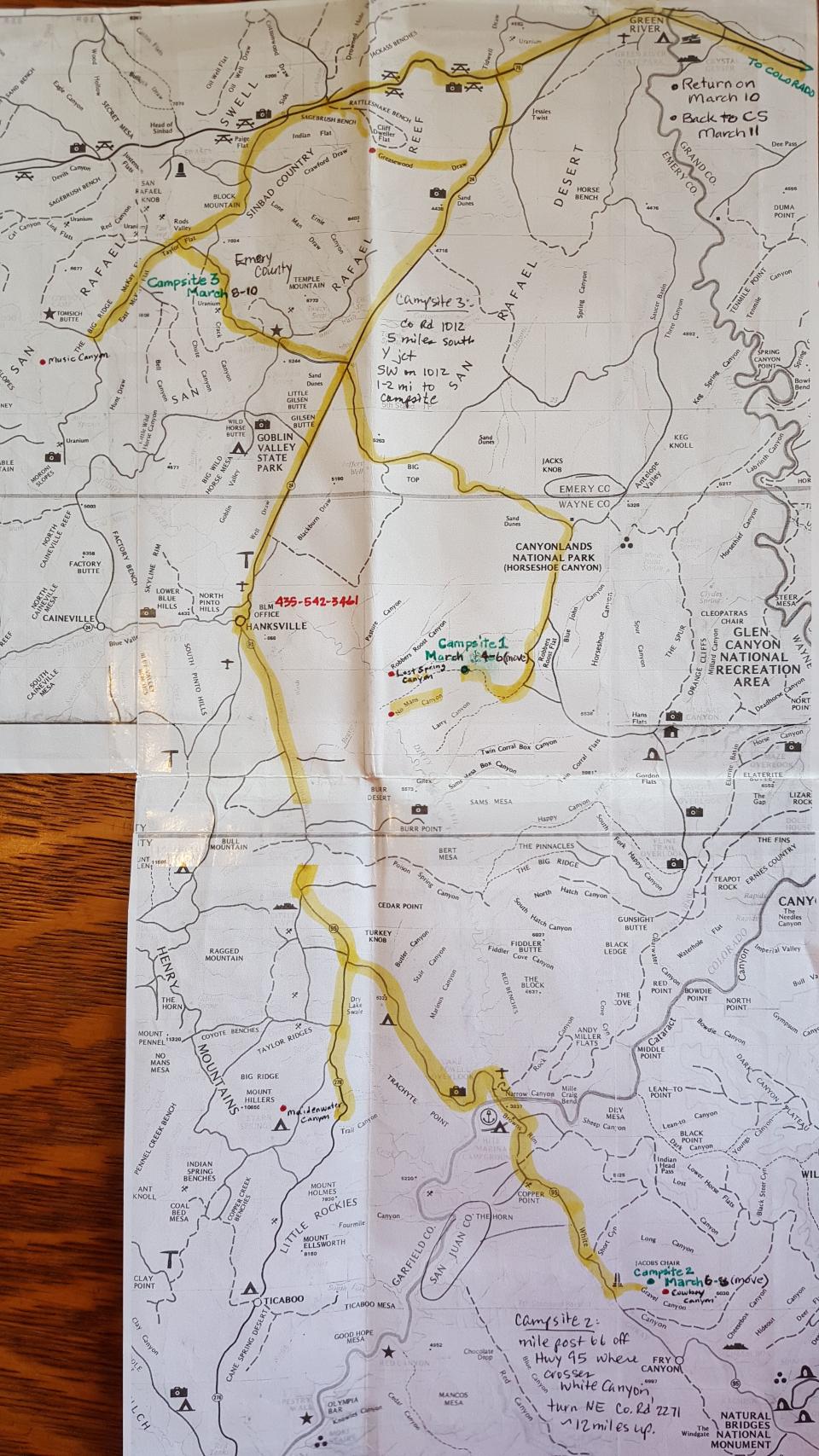

The brothers left a map before departing for their six-day trip within the steep-walled canyons. Their loved ones expected them check in on Thursday night. If a call never came, they would worry. They would send help.

David needed to stay alive long enough to be rescued. He made a decision – survive until Friday. That was five days away.

The contents of David's backpack

In the unforgiving Utah canyon lands, survival can be punishing.

The undulations of Robbers Roost, once a hideaway for Butch Cassidy and his outlaw gang, are a maze of rugged terrain. As the crow flies, David's location was just 15 miles from where Aron Ralston had become trapped in 2003.

Ralston had explored the Utah slot alone, dislodging a boulder that pinned his right arm. After five days of entrapment, he amputated the limb, fearing he would die.

David needed to survive longer.

He surveyed the contents of his backpack. The rations were thin.

The brothers had planned a full week's excursion during that spring break in March 2011 – David a college administrator on vacation from his position at Middle Tennessee State University, Louis on holiday from his professorship at Colorado Springs.

Their planned stretch through No Mans Canyon – the second day of their trip – was meant only to be a day hike.

David had packed a turkey sandwich, a Power Bar, an orange and a bag of cashews. He had a liter of iced tea, flavored with a lemon slice he cut that morning, and a small bottle of water, no more than 15 ounces.

He had also stashed some matches, a flashlight, a knife, extra wool socks and a jacket.

With his gear accounted for, David found a small, flat perch four feet above the slot's rocky floor and settled in to sleep. He cut the padding from his backpack, tucking it down his shirt to insulate his core against the chill.

That first night, as the stars sparked alive, he thought about Louis.

A younger brother in 'awe'

Growing up, people often mistook David for his older brother. They shared the same features. Brown hair, frames that stretched tall, limbs lengthy and thin.

But 13 years separated them in age. When David started kindergarten in 1958, Louis was already beginning his freshman year at Carnegie Mellon University.

It wasn't until David was old enough for college himself that the brothers spent weekends together, getting to know each other as adults.

Louis took David to eat his first meal of Asian food. He introduced David to the Grateful Dead. He taught David to play squash.

"At that time," David says, "I was in awe of him."

Eventually, David settled in Tennessee, Louis in Colorado, and they grew distant again.

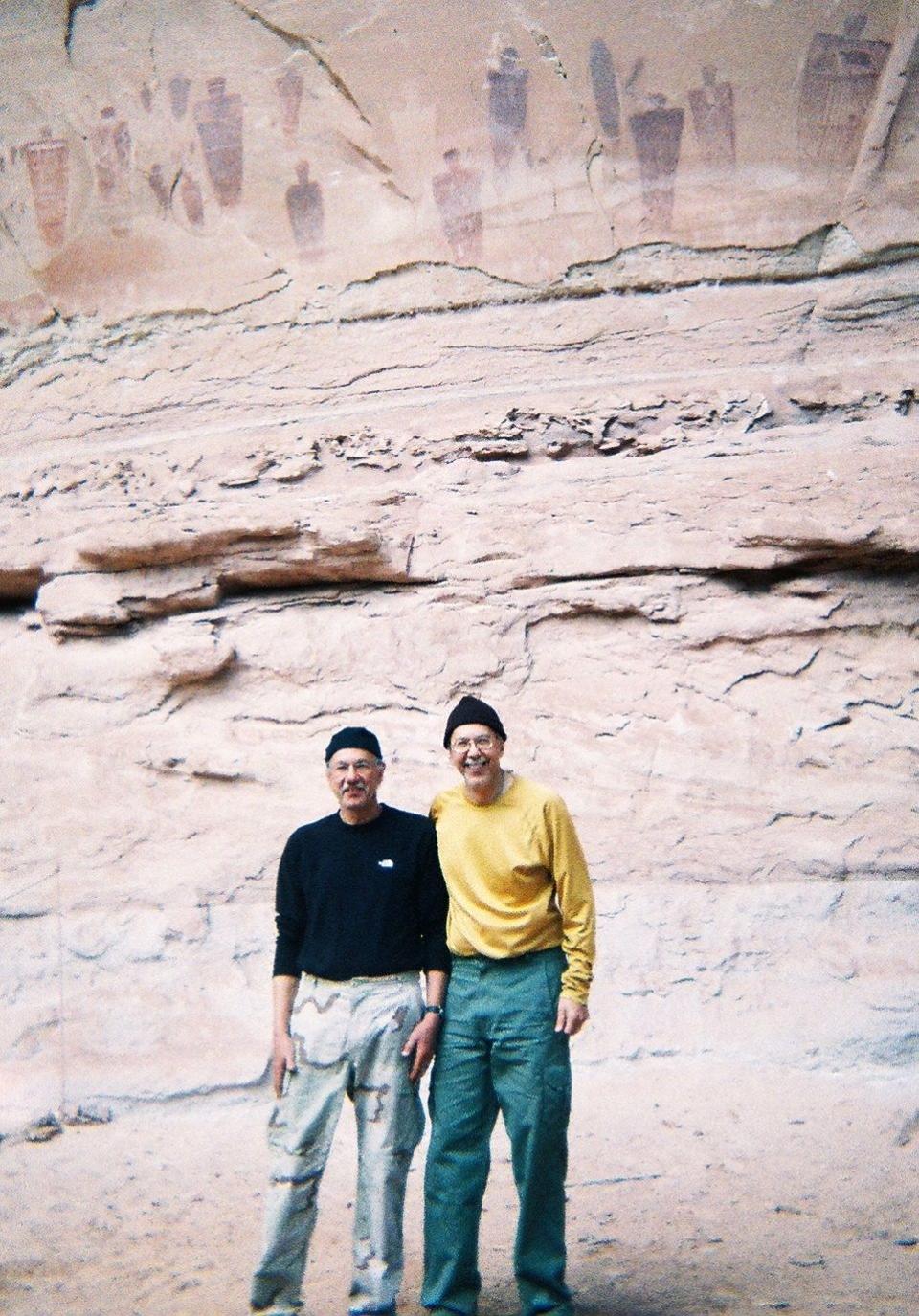

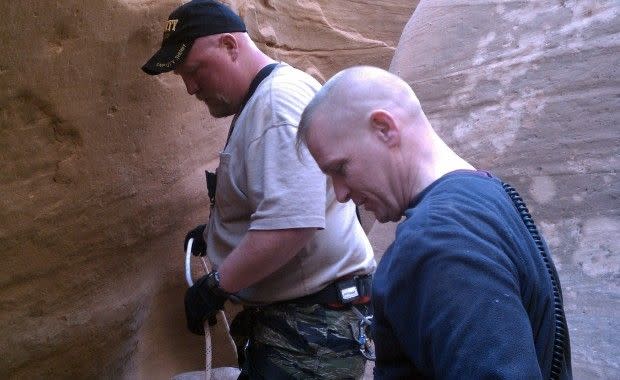

But then, as Louis embarked on regular camping trips in the wilderness of Utah, he invited David along. They were daredevil adventures that involved technical climbing. David, then well into his 50s, learned to belay, to rappel, to set up anchors.

"With these trips, we began our second phase of bonding," David says.

Often that meant nights in front of a campfire, making memories without saying a word.

The only voice in that slot

As the shadows grew dark and light across the canyon walls, David found consolation through silent and spoken prayer.

He asked for the courage to endure each night and requested comfort for his brother, whom he could not help.

He recited parts of Psalm 23 and sang "Were You There," a familiar church hymn.

"The only voice in that slot," he says, "was my own."

During the day, he peered through a tiny window slit in the canyon, watching the ravens that flew along the rocky walls. At twilight, a single bat emerged from a crevice above.

There was little plant life and no trees in the slot. When the sun set and the temperature dropped below freezing, David burned detritus he collected from the ledge. The comfort fires he lit flared for only a few minutes before going out.

He attached his extra pair of wool socks to his baseball cap, buffering his ears and parts of his face. He looked for the moon and watched Orion's Belt cross his slit to the sky.

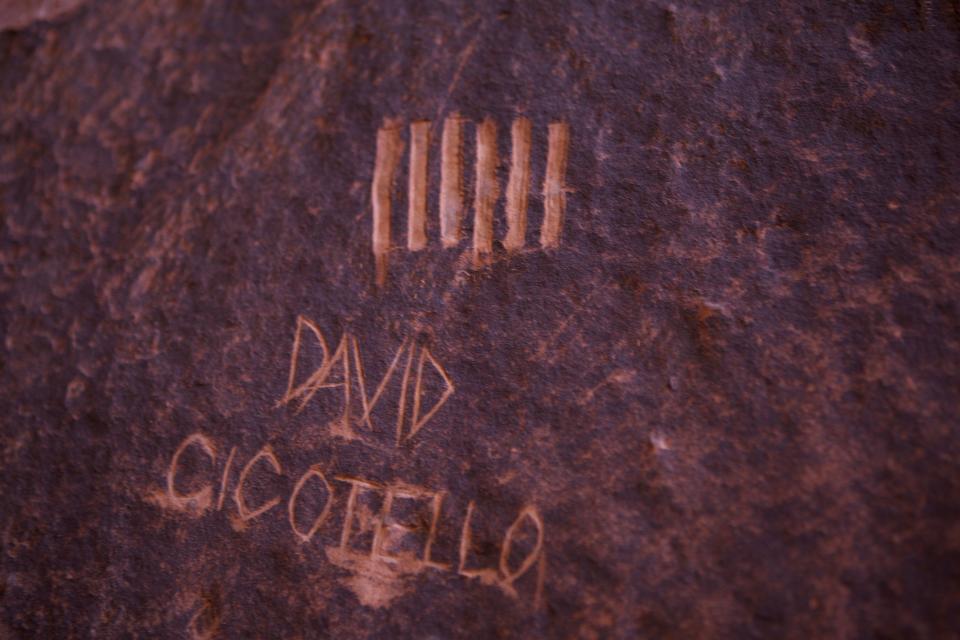

Each dawn, he etched another hash mark into the rock face where he had carved his name, counting the days. He repeated his mantra: Survive until Friday.

But as Wednesday became Thursday, he feared that rescue wouldn’t come.

A map to survival

He'd thrown out the last few bites of his sandwich when it rotted. The lemon in his tea had gone rancid and he couldn’t get it out. His lips were parched because he only allowed himself tiny sips of water. He hardly had any spit.

Without much food, David's clothing – a dark pair of hiking pants and long-sleeve yellow shirt – sagged off his frame. The cold bit hard at his fingers and toes.

He knew by then his loved ones may have realized he and Louis could be in trouble.

David had left a photocopied map with his girlfriend, Rhonda Hoffman, marking every leg of the trip. The men planned climbs and hikes across three different Utah counties.

He put a red dot at every campsite. Highlighted all the roads where they might drive. He even wrote down the number for the Bureau of Land Management.

Hoffman, an agriscience professor at Middle Tennessee State University, took the map with her on spring break to visit her parents in Missouri. At night, around the dining room table, they looked to see where David was. Hoffman didn't expect a phone call.

"There could be many days that went by that we could not hear from them because they did not have cell phone service in the canyon," she says. "You worried, but you knew they had each other and it was going to be okay."

Then, on Thursday night, her phone did ring. It was Louis' wife, Millie Yawn, wondering if Hoffman had heard from the guys.

An inkling of worry settled in her chest.

The next morning, Yawn called search and rescue in the Hanksville area near the canyon. From Tennessee, Hoffman emailed and faxed copies of the map.

By Friday afternoon, crews found Louis' white Toyota Tacoma and David's hiking journal – he hadn't written an entry in five days.

"That moment," Hoffman reflected, "was the first real, gripping fear that this was not going to end well."

The next day, a helicopter pilot called Hoffman as he flew across the canyon.

"Did they plan to hike the south fork?" he asked over the roar of the aircraft. "Or the north?"

The answer, she knew, could mean rescue or death.

The waiting. The waiting.

The helicopter first flew over David in the dark of night.

Instinctively, he stood, raised his arms and shouted, though he knew he wouldn't be heard. The chopper did not stop.

With its disappearance went the final hours of Friday – the day he had worked so hard to reach.

He was down to a few cashews, a single slice of orange and just one ounce of water. He did not want to look at an empty bottle. He refused to take the final sip.

But he was not in a panic. Even as the helicopter turned away, it gave him hope. He knew now they were looking for him. He expected they would return.

Comforted as he was, the next hours were the longest. The waiting torturous.

After 144 hours: 'I'm here!'

On Saturday, the helicopter passed over again. Once, twice, and then a third time.

The pilot spotted a long piece of webbing dangling from the rappel – and a sign that read "HELP." David had constructed it from the plastic frame of his backpack and some climbing tape, hoping a cowboy would see it coming up the canyon.

After 144 hours, it would be his salvation.

A wave of elation swept through David's body. "I'm here. I'm here," he shouted.

The helicopter signaled that it saw him. Soon, David heard boots clomping through the canyon. A man called down from the rim above

Then he reached in his pack tossed David a grape Gatorade.

"Drink that," the man instructed. David didn’t hesitate.

When the rescue teams finally reached him, they set up a winch, hauling David up the rock face he had tried unsuccessfully to scale alone.

From the canyon rim, a helicopter flew David to the hospital in Moab.

Then it returned to the canyon to recover his brother's body.

Temptation in the wilderness

In the hospital, David got three IVs and the best chicken soup he ever ate.

Then he asked to see a priest.

That evening, doctors took David to Mass. It was the first Sunday of Lent, and the gospel focused on Christ's temptation in the wilderness.

"I had just come out of the wilderness," David says. "It was the beginning of my healing."

As David unburdened himself of his brother's death, the priest gave him the last rites for healing and a Bible with Scripture to deal with loss.

Sublime always

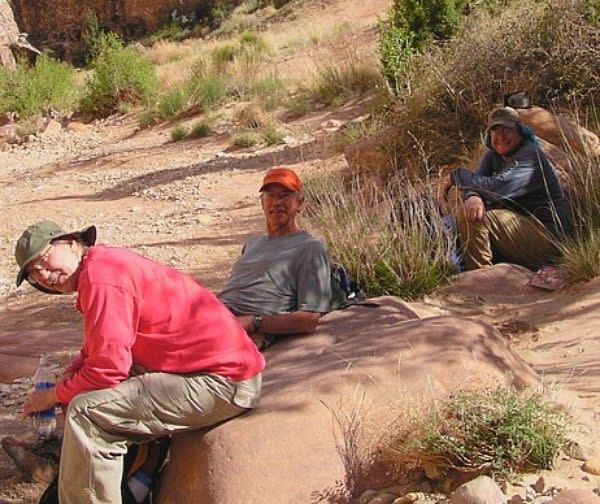

Six months later, David and Louis' wife Millie returned to the canyon with friends to scatter his ashes. They placed a carabiner at the site of his fall and left an inscribed rock as a memorial.

Louis M. Cicotello, it read. Sublime always.

An expert mountaineer, Louis was a skilled rock climber, and, up until the day of his accident, a reliably safe canyoneer.

He was 70 years old, but, as his longtime friend Rex Welshon recalls, Louis had the body of a marathoner – "a little bruised and battered but structurally sound."

Louis did three or four technical canyoneering trips a year. He had probably completed more than 800 rappels in his life.

"Louis was the best kind of mad man," Welshon says. "He was endlessly enthusiastic. Very well educated. And it was a blast to be on a desert trip with him. We could talk on and on and on and on about very philosophical topics while sitting on edge of canyons looking at the sunset."

'Every one of us is on a ledge'

It's inevitable to speculate about what happened to Louis after David lost sight of him.

Steve Kugath, a faculty member in the Recreation Management Program at Brigham Young University Idaho, says, "No one knows exactly."

A year after Louis' death, Kugath visited the site. Working on a database of canyoneering accidents, he wanted to understand the dangers and hoped to minimize future accidents.

That day, as he paused to photograph the beautiful scenery overhead, he discovered David's carvings on the canyon wall.

"The concept of eternal life means this life is really but the blink of an eye," Kugath says. "And yet, I felt great empathy for David, trapped on that ledge not knowing the fate of his brother."

Many who know the story say David's perseverance in the face of such grief and seclusion is one of the most remarkable tales of survival they have ever heard.

For David, it's the commonality – not the uniqueness – that connects him to others.

"Every one of us is on a ledge," David says. "Out there someone is going through a divorce. Facing bankruptcy. Dying of cancer.

"Survival is the most common denominator."

Follow the Tennessean's Jessica Bliss on Twitter @jlbliss.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: He survived 6 days trapped on a ledge in a Utah canyon after his brother fell to his death