They survived school shootings. Now their own kids are in classrooms amid rising epidemic.

Columbine survivor Missy Mendo was filling out pre-K registration paperwork for her 4-year-old daughter, Ellie, when she saw the news Tuesday about the nation's latest school shooting.

"I had to walk away from the computer (to) take a fresh breath of air," said Mendo, whose daughter starts this fall at a school just down the street from Columbine High. "I felt this huge sense of horrendous loss in the world."

Now 38, Mendo was a 14-year-old freshman at Columbine in 1999. The massacre, which killed 12 students and a teacher, was once the deadliest school shooting in the U.S. It keeps dropping further and further down the list.

Last week, a gunman opened fire at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, killing 19 children and two teachers. For survivors of school shootings who've grown up to have kids, the incident is a traumatic reminder of what they went through – and the difficult decisions they must make for their own children.

"Every time this happens again, of course it breaks our hearts over and over," said Randa Samaha, 36, whose younger sister was one of 32 people killed in the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting. "Now that I have children, it's hard to not imagine their faces as the victims."

Samaha, then a 21-year-old student at the University of Virginia, was at the doctor's office that day when she saw the news on TV. Her husband, Zachary Madrigal, now 33, was classmates with her sister, Reema, and searched the campus for her on his bicycle. The couple now have three children: a 2-year-old son and twin 6-month-old girls.

"Just after this most recent shooting, my husband was saying, 'I feel like we should homeschool our kids,'" Samaha said. "We know that you can never protect them from everything, but are we fools to be sending them to school when they're of age? Or do we keep them home where they’re not going to be in a school shooting?"

'It hits differently now'

In the years since Columbine, thousands of students on school and college campuses across the nation have been exposed to shootings. Gunfire on school property is at an all-time high, and firearms are the leading cause of death among children and teens in the U.S.

At K-12 schools alone, there have since been 1,390 shootings on school grounds, according to the K-12 School Shooting Database at the Naval Postgraduate School's Center for Homeland Defense and Security. Of those, 114 were active-shooter incidents, and four were planned attacks at elementary schools.

It's an accelerating problem: More people have died in mass killings in schools in the past five years than in the prior 12 years combined, according to a database of mass killings kept by USA TODAY, The Associated Press and Northeastern University.

IT'S NOT JUST UVALDE, TEXAS: Gunfire on school grounds is at historic high in the U.S.

IN GRAPHICS: School shootings are on the rise. More kids are dying from gunfire outside of school, too.

It's in such a climate that survivors of school shootings are growing up – and sending their own kids to school.

The classmates of the five girls killed in the 2006 West Nickel Mines School shooting in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, are in their 20s now. The youngest classmates of the eight students shot to death at Umpqua Community College near Roseburg, Oregon, in 2015 are in their mid-20s.

Many of the classmates of the five students killed in the 2008 Northern Illinois University shooting in DeKalb, Illinois, and of the six students killed in the 2012 Oikos University shooting in Oakland, California, are in their 30s and 40s.

"I honestly don't really know how to talk about this with my girls yet and am actually dreading if they bring this up," said Colin Goddard, who was shot four times in his French class at Virginia Tech when he was a 21-year-old senior.

Goddard now has three children – 1, 4 and almost 6 – and a fourth on the way. His oldest children just started kindergarten and pre-K.

"The thought of something happening at their school is too overwhelming to even consider or really think about for very long. Just like how overwhelming it still is thinking back to being in that classroom in 2007," he said.

Kristina Anderson was a 19-year-old sophomore when she was shot three times at Virginia Tech. Now 34, Anderson has two children, almost 2 and 8 months.

"Many of my friends and survivors from Virginia Tech are also recent parents, and there's a consensus – that it hits differently now," Anderson said. "I've corresponded with a survivor parent who talked about having the strength to decide whether or not to send her child back to school the following day. I'm devastated at the fact that this is a decision I may have to make in the future also for my kids."

Every time there's another school shooting, it opens up a new wound – a "ripping, twisting stomach pain," Samaha said. Since the shooting in Uvalde, she has been plagued by "what-ifs."

"After my sister was killed, it was 'What if?' What if her alarm hadn't gone off and she didn't make it to class? What if I had talked to her longer at night and kept her up late so that she slept in?" Samaha said.

The day after the Uvalde shooting, Samaha sent her son to day care. "I was feeling almost guilty," she said. "You can't help but think, 'What if?"

'Absolutely terrifying' sending kids to school

The "absolutely terrifying" thought of sending her daughter away to school prompted her recent return to therapy, said Mendo, of Littleton, Colorado.

Mendo, who lost her good friend Daniel Rohrbough in the Columbine massacre, was diagnosed with insomnia after six weeks of therapy. She finds herself once again seeking help with her mental health.

"How do you kiss your baby goodbye and send them to school knowing these things are still happening? How – how do I do it?" Mendo said.

Twenty-three years ago, Mendo was sitting in math class when she heard what sounded like someone banging on lockers and a loud rumbling.

The rumbling was a stampede of students running down the halls. The banging on lockers turned out to be gunfire. "Somebody started yelling, 'They have guns, they have bombs,'" Mendo said. "The fire alarm went off and we all started running."

She and her group of classmates made it to safety off campus – but not before being shot at while standing in the park across from the school, Mendo said. She escaped uninjured, but the trauma has endured well into adulthood.

'AN INSTANT REPLAY OF SANDY HOOK': They thought Sandy Hook would 'wake up' the US. Uvalde school shooting proves it didn't.

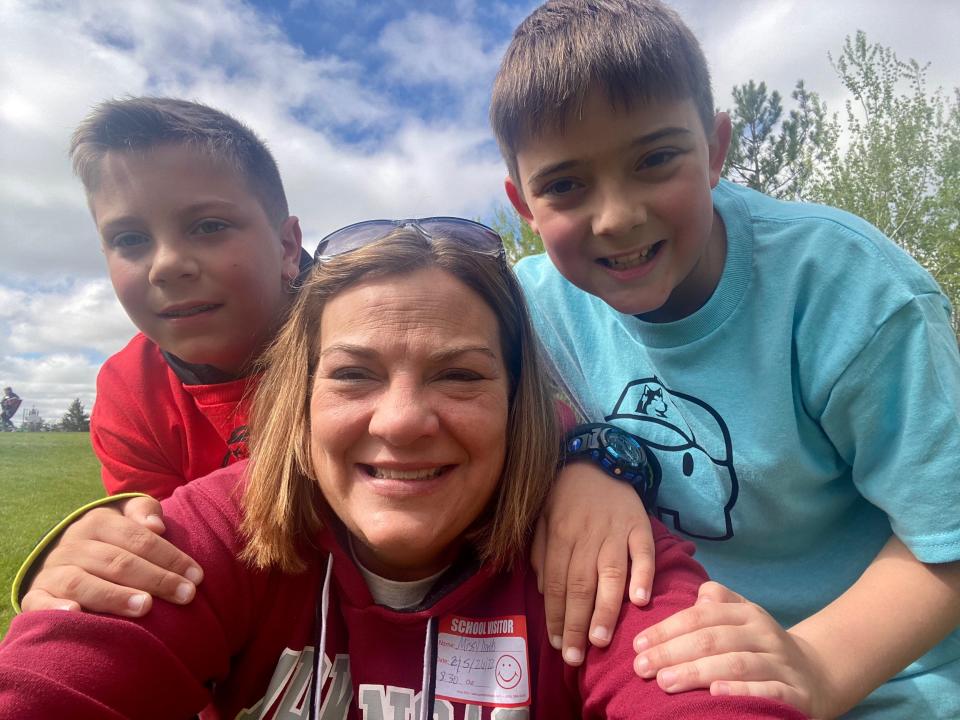

Missy Dodds, 47, said she broke down Wednesday when she saw the flag at half staff while dropping her 9-year-old twin boys off at school. She pulled it together as she drove to drop off her daughter, 11, but "cried and cried" when she returned home.

When Dodds became a mother, she was determined that her kids would have a normal school life not marked by the trauma she endured 17 years ago when a former student shot his way into her classroom at Red Lake High School in Minnesota.

But she struggled when she sent her three kids off to kindergarten for the first time. And she struggled again when dropping them off at elementary school after learning about the Uvalde shooting.

"This one to be completely honest with you has been extremely hard for me because I have three kids now," the former math teacher said. "Every school shooting hurts me, but this one has been so different because my kids are the same age."

Dodds still lives in Bemidji, Minnesota, where the March 21, 2005, massacre took place. But she hasn’t been able to return to teaching since the gunman killed five students, a teacher and a security guard as well as his grandfather and his grandfather’s partner.

She has been in therapy ever since, and she has worked through her PTSD to the point that she’s able to talk about her experience. After her daughter finished first grade, she worked with two parents of Sandy Hook victims to become a school safety advocate through their nonprofit Safe and Sound Schools.

"I'm forever grateful for them," Dodds said. "They've helped me know what needs to be done."

'I couldn't handle it'

Not all school shooting survivors went on to start families. In some cases, the trauma they lived through is partly why.

"(I'm a) Columbine survivor, and my experience is one of the reasons I don’t have children," Lindsey Fry wrote on Twitter in response to a thread started by a former classmate. "I couldn’t handle it."

Joshua Hevert, who grew up in Colorado and was a senior at Columbine that day, said the sense of death that seemed to linger over Littleton contributed to his choice to hold off on being a father. "After all of that death, it made me rethink kids completely," he said.

Hevert, 41, used to teach high school and now works at a community college in El Paso, Texas. Despite not having children of his own, Hevert said, the desire to ensure the safety of the 15- to 17-year-olds he once taught remained at the forefront of his mind.

He said the school's intense active-shooter drills – the banging on the doors, the shouts for help, the instructions to remain silent – would transport him back to 1999 with anxiety and a racing heart.

"I got out really quick, but, you know, there was still that 10 to 15 minutes I was in the school during the shooting," said Hevert, whose forensics and debate teammates, Daniel Mauser and Rachel Scott, were killed. "There are plenty of memories, plenty of trauma."

The drills led to some tough conversations with his students, Hevert said.

"I told them over and over again that if this happened to us, this is what I would do to protect (them)," Hevert said. "I wanted them to at least know that I wanted to protect them, that I loved them and that I would do anything in my power to prevent harm from coming to them."

'Being where they need to be'

Several survivors said that despite their fears, they want their children to go to school and experience a "normal upbringing."

Former Columbine student Mandy Cooke, 39, now teaches at her alma mater, along with several other former classmates who survived the shooting. She and husband intentionally moved back to the area so their kids – Wyatt, 10, and Ryder, 8 – could one day attend Columbine.

"I don't let April 20 and what happened that day define me, and I certainly don't want to put that on my kids," Cooke said.

Others agreed. Goddard said he doesn't want his own worries to keep his kids from "being where they need to be to learn and grow into healthy adults."

He said his own experience as a survivor has prompted him to teach his kids the value of socio-emotional learning and the importance of how they treat their peers. But he's not sending them to school with "a bulletproof backpack."

"I get that deeply fear-driven logic, but that would be giving up and accepting this phenomenon as the norm. But it's not. It's a choice that a tiny number of human beings in Washington, D.C., have chosen to make," Goddard said.

'PRAYING FOR MYSELF TOO': Parents struggle with goodbye after another school shooting

Anderson said she "definitely" plans to send her kids to school. Her organization, The Koshka Foundation for Safe Schools, is focused on preventing and responding to mass shootings and healing in the aftermath.

She already knows she wants to be "a very involved parent" in the arena of school well-being, safety, security and emotional health, prepared with questions for administrators about emergency preparedness and training, Anderson said.

Mendo, who graduated from Columbine in 2002, said she feels better about sending Ellie to school after researching the security protocols in place there. The school has cameras and a security company that monitors the campus, she said.

'Decide as a parent what you want to say'

When Ellie is older, Mendo will talk to her child about Columbine. She has gotten advice from other survivors through The Rebels Project, where she is a community outreach director.

The organization, founded and run by survivors of mass shootings, connects those who have escaped disaster to a network of others carrying similar burdens of trauma.

"It's not a one-step answer," Mendo said. "You wait until they may start asking questions depending on their age and their level of comprehension, and then decide as a parent what you want to say and how you want to say it."

Mendo knows she’ll need to prepare for how she’ll react when Ellie comes home and says there was a drill at school. She’ll quiet her inner worries while letting her daughter communicate openly about what she has experienced, she said.

Cooke said her youngest son doesn’t yet know his mother’s story of surviving the Columbine shooting, and she prefers to keep it that way for as long as possible. Her son Wyatt found out through a classmate’s older brother, she said.

"One day, he said: 'Hey Mom, there were two shooters at Columbine. Do you know what happened?'" Cooke recalled. She said she intentionally kept her story brief and will hold the details until he’s older.

Dodds said she has talked with her kids in an age-appropriate way about her experience at Red Lake – not wanting them to hear about it from someone else – and worked with their school district and law enforcement to build an emergency operation planning team.

"(That’s how) I'm able to send my kids to school. As long as I know that we're doing everything we can," Dodds said. "I want my kids prepared. I hope and pray that we get to a place that this is not something that we have to practice in school anymore."

After school on Wednesday, in the wake of the Uvalde shooting, Dodds said she texted a fellow Red Lake survivor during her sons' baseball practice and searched the ball park until she found them.

"Because they know my heart," she said. "And I needed that hug so bad."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: School shooting survivors fear sending kids to class after Uvalde