Surviving Korea: Marine veteran from St. George, Utah recalls combat 70 years later

Whistles and horns shattered the silence of a frigid evening in a foreign land. As flares lit up the sky, Chinese troops materialized out of the snow and charged toward American lines. Atop a hill just to the west of the Chosin Reservoir, Ed Barberis, a 20-year-old marine from Homedale, Idaho, was under siege.

As he fired bursts from a machine gun, Barberis prayed that he would see another day.

The Battle of Chosin Reservoir, among the most storied battles in the history of the U.S. Marine Corps and a turning point in the Korean War, had begun. The surprise Chinese intervention at the Chosin 71 years ago turned what appeared a sure victory for United Nations forces into a bloody fight to avoid annihilation.

A retired Greyhound bus driver who logged nearly two million miles on duty, Barberis, 91, has lived in St. George for 28 years. The sounds, smells and memories of battle have never left him. He often thinks about those perilous times seven decades ago in North Korea, when survival was his only objective.

“My bucket list at the time was to get home, get married, create a family — do all the things you plan on doing with your life,” Barberis says. “I didn’t want anything to keep that from happening. Consequently, I offered up a lot of silent prayers.”

As he fired on the ceaseless enemy, Barberis knew one thing.

Tomorrow was far from promised.

The call of the Corps

A native of Oshkosh, Nebraska, Barberis’ family struggled to make ends meet during the Great Depression and the early years of World War II. They gradually moved west until they settled in Homeland, Idaho, a tiny farm community about 40 miles west of Boise.

Barberis’ teenage years were filled with the imagery of WWII fighting men. One was his brother, Albert, who served with the Marine Corps in the Pacific. When Ed saw his brother’s dress blue uniform, it was love at first sight: He was going to become a Marine.

Barberis enlisted in January of 1950 at age 19 and was assigned to E Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Marine Regiment. Six months later he boarded a ship bound for South Korea. The matter was urgent. On June 25, Communist forces of the Korean People’s Army (KPA) crossed the 38th parallel and invaded Seoul. South Korean troops fought back but were pushed southward — nearly to the Sea of Japan.

In coordination with the United Nations Security Council, U.S. President Harry Truman sent forces to stem the tide. On Aug. 6, Barberis saw his first day of combat on the Pusan Perimeter as fifth ammunition bearer for a machine gun crew.

“Now we have the enemy firing live ammo and artillery at us,” Barberis says. “This changed the ballgame. We are facing the reality that we could become a casualty at any moment.”

On Aug. 17, E Company began an attack along Obong-ni Ridge. The machine gun crew’s task: to cover the advance of the assault units near the Naktong River. Due to attrition, Barberis had become the gunner’s assistant. Typical machine gun maneuvers involve firing bursts and displacing to a new location — making it difficult for the enemy to pinpoint your whereabouts.

“We moved a fourth time back to our original spot. I had just fed the belt into the gun when we got hit. A lucky shot,” Barberis says. “The bullet shattered the weapon ... shrapnel and rocks blew up and hit me on the right side of my face and neck. Luckily it wasn’t a fatal shot. It could have been.”

The gunner, laying a foot or two to Barberis’ right, was hit worse.

“I could see something sticking in his neck,” recalls Barberis, who suffered minor wounds. “I had to try to get him off the hill, so I grabbed a hold of him by the feet. We got him into a jeep to go to the field hospital. He was not responsive at all.”

Barberis’ comrade, Private First Class Raymond Lee Tuttle, not yet 19, was killed in action.

Bold moves

General Douglas MacArthur made a career of taking calculated risks a more timid man might forgo. One of his great triumphs was the surprise landing at Inchon on Sept. 15, 1950. This allowed U.S. forces to flank a large chunk of Communist forces in the South.

By then, Barberis had returned to his unit and fought from Inchon inland to the capital city, Seoul. Barberis, now promoted to machine gunner due to attrition, provided fire support to Marines clearing buildings. Heavy casualties were sustained.

Still, U.S. forces had momentum. When the situation south of the 38th parallel appeared under control, MacArthur challenged his troops to push north toward the Yalu River, which creates the boundary between Korea and China. He wanted to end the war, going so far as to promise his men that they would be home for Christmas.

On Nov. 23, Barberis was in the mountains of North Korea settling in for Thanksgiving dinner. Surprisingly, it included all the trimmings. Turkey. Mashed Potatoes. Gravy. Dressing. Pumpkin pie. It was appreciated, this little piece of home. Yet it wasn’t enough for them to forget about the cold.

“It was 30 degrees below,” says Barberis, promoted to Private First Class. “Our cotton gloves didn’t afford much protection. The footwear we had was not adequate. You’d get your body heated up and then you would sit for an hour and freeze.”

Communist China was about to enter the war. More than 120,000 Chinese soldiers waited for just the right moment to strike.

Chinese attack

First came the whistles. Then the rifle fire. It was late in the evening of Nov. 27. The Marines were under attack.

“We didn’t know that they were Chinese or who they were,” Barberis says. “You just know that there are shots coming toward you and you just return fire.”

Barberis blazed away on the .30-caliber machine gun. In many combat situations, the defenders can dig foxholes or trenches to provide cover. Not in the Chosin Reservoir. The ground was too cold. Barberis got as low as he could while sending bullets into the enemy.

In some sectors, the Chinese overran Marine positions. Chaos ensued. Much of the battlefield deteriorated into hand-to-hand combat. American forces, including those in Barberis’ unit, inflicted heavy casualties. Barberis recalls the morning after the initial attack, he saw dead Chinese about 15 feet away from his position.

The Battle of Chosin Reservoir was a crisis of enormous proportions. Due to the overwhelming manpower of the Chinese — they held a 4:1 advantage in committed troops — American forces in the vicinity were on the verge of obliteration.

Working against the Americans was that there was only one way out: the narrow Main Supply Route (MSR) that the Chinese were in position to cut. It would be a perilous journey — but not a retreat. According to Marine General Oliver P. Smith, it was “attacking in a different direction.”

Withdrawal. Retreat. Attack. Call it what you want. The breakout from the Chosin Reservoir was a long, snaking line of humanity through a valley under the threat of lethal force at all times.

“We felt like fish in a rain barrel,” Barberis says. “No matter where you were, you were in the line of fire.”

Step by painful step, sometimes holding onto a truck or jeep, Barberis and the men of the 5th Marines braved the cold temperatures, snipers and lack of food and water. In about a week’s time, they hobbled from their outpost in Yudam-ni to Hagaru-ri, 18 miles to the southeast. From there, Barberis was airlifted to the coast.

Suffering from significant frostbite in his toes and feet, Barberis was evacuated to Yokosuka Naval Hospital in Japan. He made a quick recovery and was moved to a hospital in Oakland, Calif. On Dec. 23, he was released. On Dec. 24, he was back in Homedale.

As far as Barberis is concerned, MacArthur kept his word. He was home for Christmas.

Gratitude

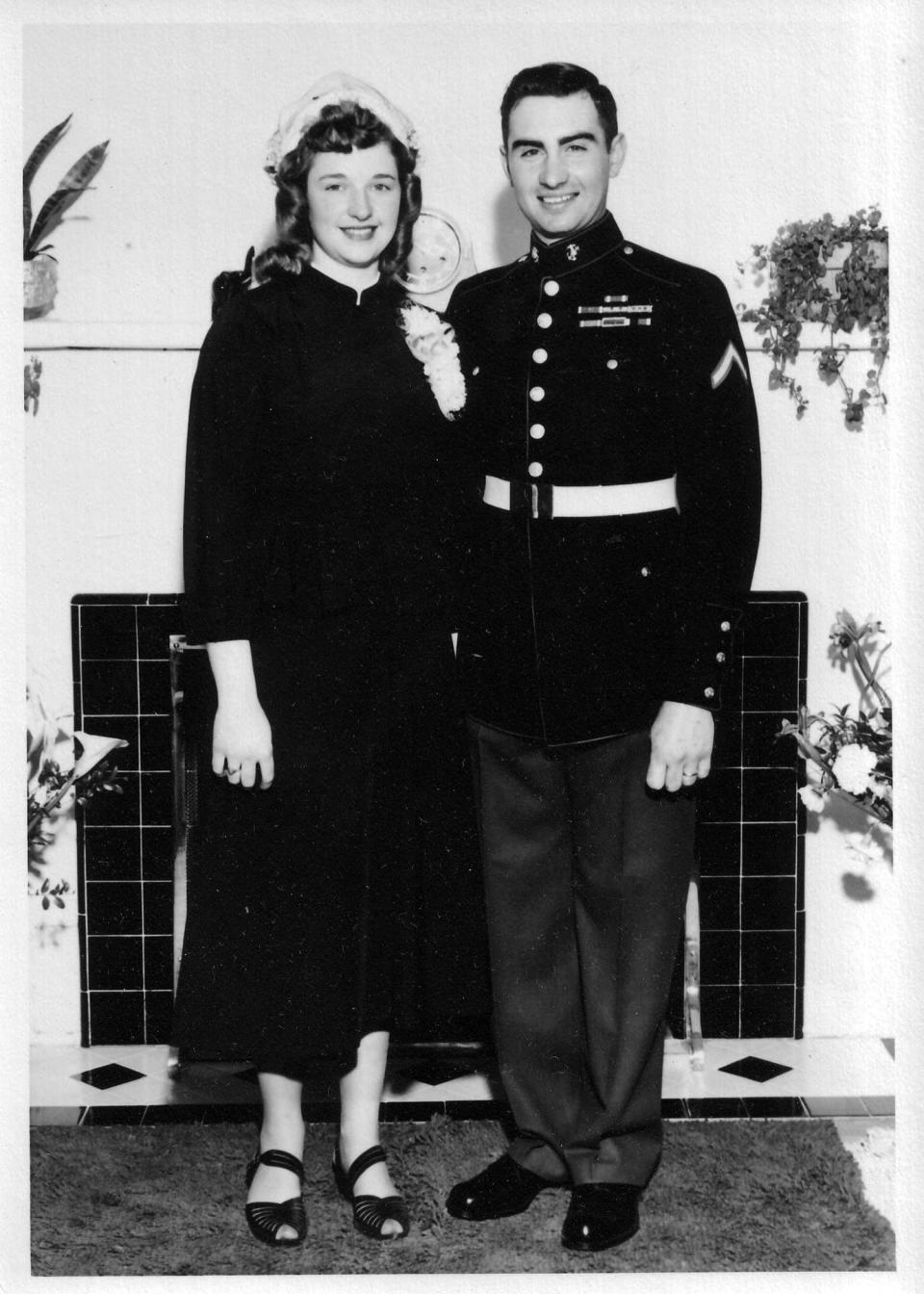

Barberis had a joyous homecoming. Wearing his dress blues, he married his sweetheart Ruth on March 10, 1951. They remain married and look forward to their 70th anniversary.

He completed service in the Marine Corps as a bookkeeper in Pocatello, Idaho — an assignment for which he feels fortunate. In 1954, he was honorably discharged. He owned a service station and sold insurance for a bit, but he found fulfillment as a bus driver. He spent nearly 30 years behind the wheel.

The nonagenarian continues to move freely, though he still experiences physical effects from the war. Shrapnel remains in Barberis’ neck; pieces of rock and steel have worked their way to the surface over the years. The skilled treatment of doctors in Japan saved his feet and toes. On cold mornings, though, he is reminded of the frostbite.

He had two kids, six grandchildren and 15 great-grandchildren. “Every prayer was answered,” he says.

Barberis has no regrets about his experiences in what is referred to as The Forgotten War. And though Korean War veterans garnered far less attention than those who served during WWII, Barberis says these days he is the recipient of plenty of gratitude.

It did take a while, though.

He recalls waiting to get a haircut when a fellow veteran struck up a conversation. One of the barbers, an Asian lady, happened to overhear them. When it became Barberis’ turn, she asked him about his military service. When it was apparent that he fought in Korea, the barber told him that when she was a kid, the North Korean army chased her family out of town.

The marines, she said, gave her back her home. And although he was 75 at the time and she wasn’t a whole lot younger, she never forgot what had happened so many years ago.

His haircut was on the house.

This article originally appeared in Inside St. George, a publication produced by the City of St. George. The author, David Cordero, can be reached at david.cordero@sgcity.org.

This article originally appeared on St. George Spectrum & Daily News: Surviving Korea: Marine veteran from St. George, Utah recalls combat