'The Survivor' is not about the boxing, but what comes after

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

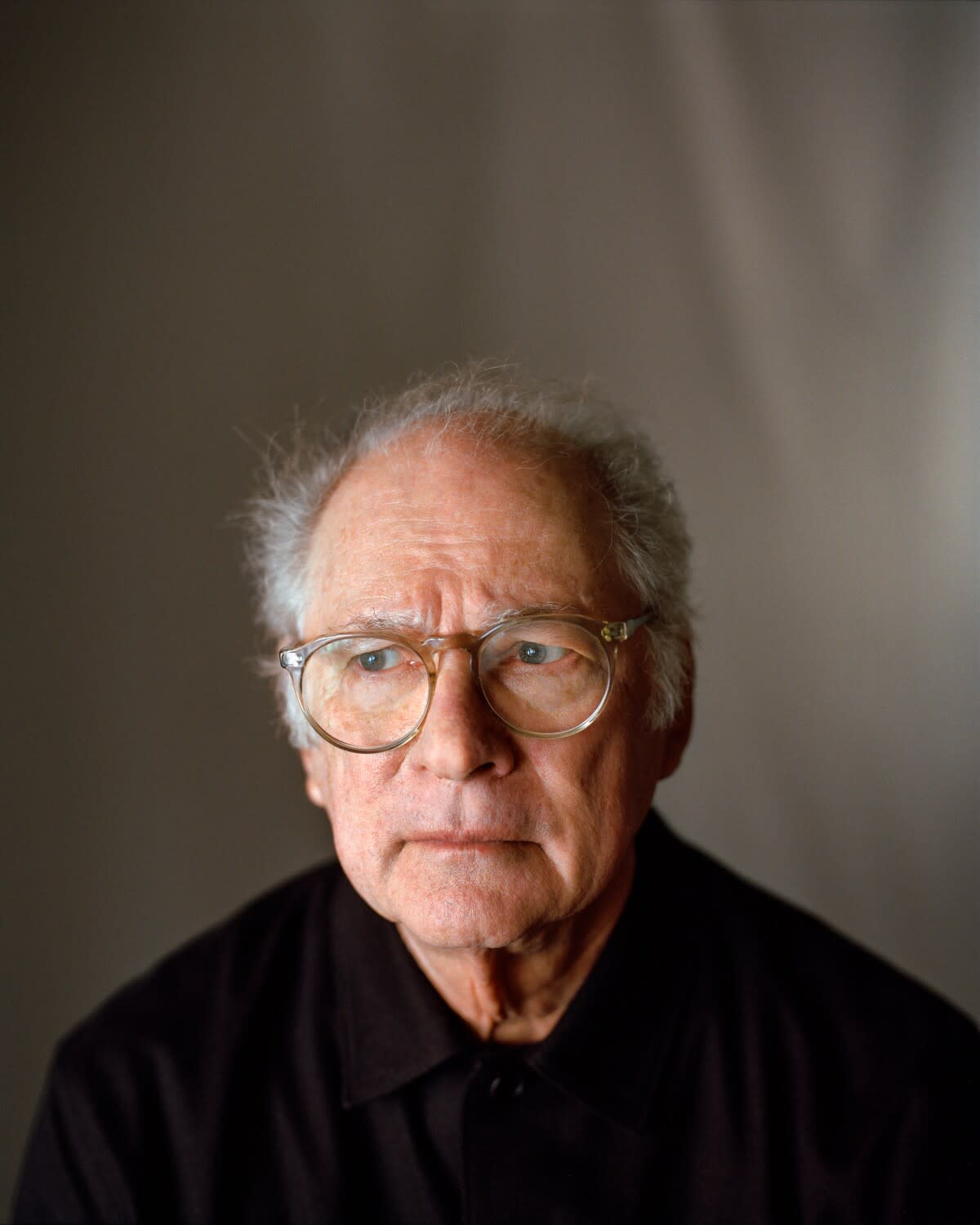

It was the memory of Uncle Simcha that prompted Barry Levinson to direct his latest, HBO's “The Survivor.” Levinson was a boy of 6 when a stranger turned up on the doorstep of his Baltimore home. The mysterious figure was named Simcha and he turned out to be Levinson’s grandmother’s brother. He stayed with the family for a short while, sleeping in a spare bed a few steps from where Levinson slept.

“I hear him yelling in a language I didn’t understand. He was tossing, turning and saying these things and was obviously real upset. And then he fell back to sleep,” Levinson recalls. “Night after night after night that same thing would occur. After two weeks, he moved out and ultimately he moved to New Jersey. And no one really talked about him in the house.”

It was only years later, when he learned Simcha was a concentration camp survivor, that Levinson began to put the pieces together. That is why “The Survivor,” about real-life Auschwitz prisoner Harry Haft who fought fellow detainees to the death for the amusement of their captors, isn’t really a boxing film, but a film about post-traumatic stress disorder.

“That’s what he was suffering from,” Levinson says of Uncle Simcha. “No one ever had a name for it. From the soldiers of World War II to the soldiers of Vietnam, to the soldiers throughout the world who’ve fought in these various things, many of them can’t get rid of the past and it haunts them, it affects their relationships. Harry Haft, he did survive the camp, and then he had to find a way to really live a life thereafter.”

Living that life on the screen is Ben Foster who dropped 62 pounds for the Auschwitz scenes. “When you're at deficit, it just means you have less energy. So then it’s about finding resources that you didn't know you had. I’m not comparing my experience to a survivor, but I could get as close to deficit as I could in order to explore where are my resources when I thought I had none,” says Foster, who’s in nearly every frame of the movie. “So yes, taking off a shoe became laborious in a way that informed the rest of the film. Because even when Harry’s got weight on, the skeleton's still inside and you carry that with you. And having been through that in an essential and physical way I knew was going to help inform the rest of the picture.”

Although Haft had a brief career in the ring, even losing to Rocky Marciano in 1949, he wasn’t a boxer when he fought at Auschwitz. “He's really fighting to survive, so it’s a bit reckless and he doesn’t have the moves of a boxing pro. So the approach is to be as messy as we see on screen,” the director says.

Stunt coordinator Clayton Barber choreographed the film’s fight sequences, but mainly Foster and his ring partner would semi-coherently scrap their way through. “The hits are hits,” notes Foster. “I’m not saying we’re trying to knock each other out, but a little bit of contact wakes you up. Learning to box at deficit was a real interesting corkscrew.”

Intercut with cinematographer George Steel’s gritty black-and-white prison camp sequences are colorful postwar scenes set in New York City, where Haft searches for his long-lost love who may have died in the camps. For those scenes as well as the last act set in the early 1960s, Foster added 50 pounds. More challenging than the physical demands, though, was the emotional rollercoaster of the role as well as visiting Auschwitz during preproduction.

“This is literally a factory to kill people. It’s beyond comprehension. And then we have various kinds of guides that would inform us about various things that I think made their way into the film,” recalls Levinson, who worked from a script by Justine Juell Gilmer based on the 2006 memoir by Haft’s son, Alan Scott Haft. “This story is about survivors. If you look at Ukraine and you see all these people, all these refugees that ultimately have to try to get out of there to avoid all of the kinds of indiscriminate killing that takes place throughout the country, bombing a railroad station where people are just trying to get out, it’s inhumane. Some of them will be scarred forever with this post-traumatic stress that you cannot put behind you.”

Levinson and Foster were introduced in the late '90s when the actor made his first big screen appearance in “Liberty Heights.” He played a high schooler during the civil rights era who falls for a Black girl played by Rebekah Johnson. “Barry shaped the actor that I am today,” says Foster. “He’ll change something up, he’ll encourage improvisation. He’s deeply fascinated with human behavior and all of our human idiosyncratic frailties. Getting to work with him again in this way, it’s such a pleasure.”

If nominated for an Emmy, it will be Levinson’s 12th, with four wins. He’s also the recipient of three Golden Globe nominations, six Oscar nods and a win for “Rain Man.” “It doesn't get old. It’s nice that you do something and somehow it gets recognition in some way,” he modestly says. “It’s nice there's recognition for the actors you’ve worked with, or the cinematography.”

Next up for Foster is “Hustle” with Adam Sandler, and “Emancipation” with Will Smith. Levinson is prepping “Sheela” starring Priyanka Chopra Jonas as Sheela Ambalal Patel of the controversial Rajneesh movement. He’ll also direct “Francis and the Godfather,” starring Oscar Isaac as Francis Ford Coppola, and has numerous other titles in development. Still going strong at 80, the prolific filmmaker has no intention of easing up on an illustrious career. Uncle Simcha would be proud.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.