Susan Campbell, writer and illustrator who reignited interest in historic walled gardens – obituary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

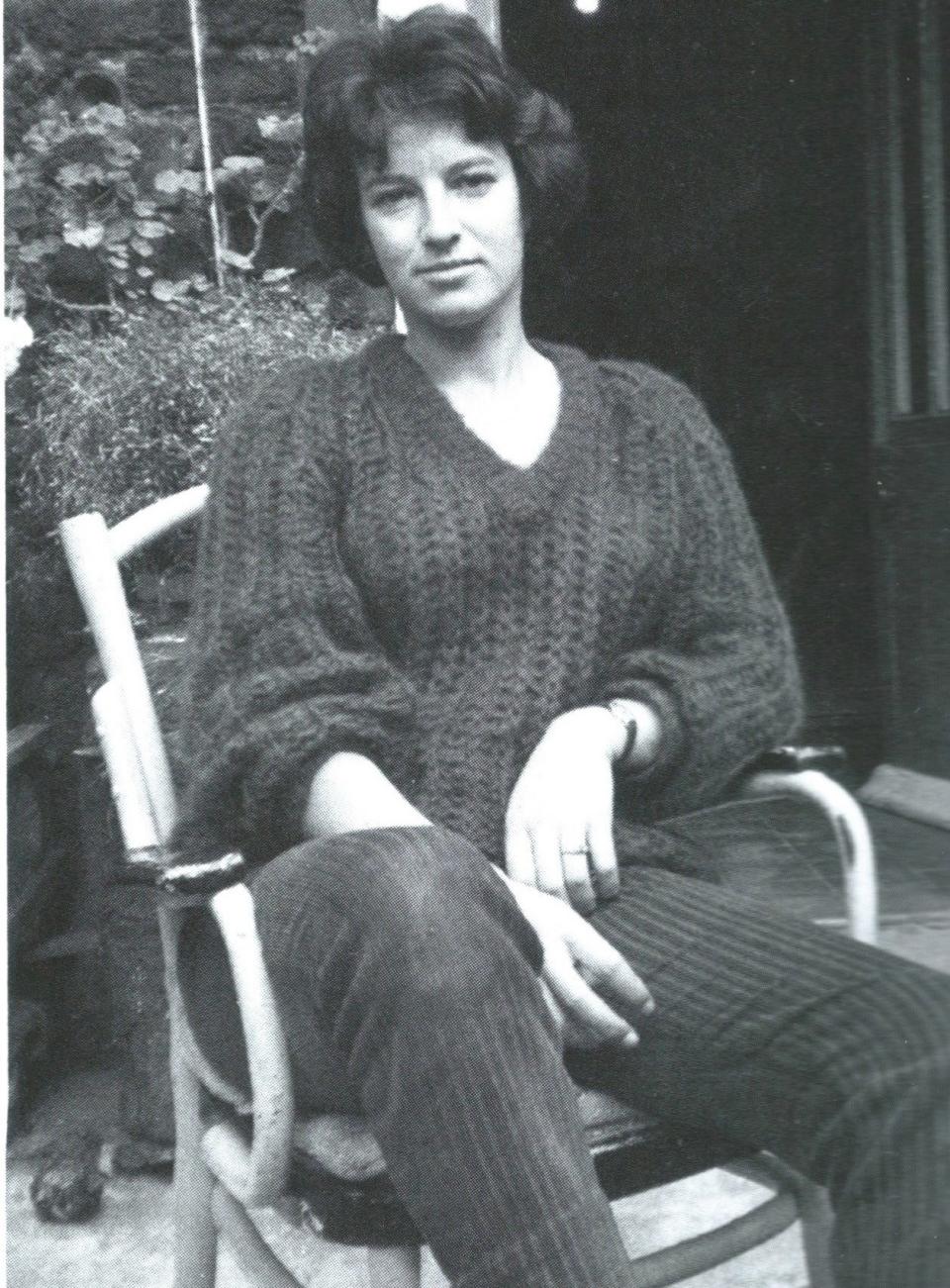

Susan Campbell, who has died aged 92, had a long and varied career as an artist and illustrator, a food writer and Britain’s leading expert on walled kitchen gardens, 700 of which she visited in the UK and abroad.

Susan Jennifer Benson was born in Ruislip on September 14 1931, the daughter of Herbert Benson and the former Agnes Groner. Her family was originally from Bavaria, where her paternal grandfather was a merchant in cycle parts and accessories and her maternal grandmother was the daughter of a well-off furrier.

They were naturalised in Britain in 1903 and later took the name of Benson – as Susan put it, “to get into the golf club”. Her father imported fancy goods from Germany and Japan.

She was one of 80 pupils at Chilterns School, Monks Risborough, Bucks, run by John Brophy, father of Brigid Brophy. She then studied painting and drawing at the Byam Shaw School in Kensington, becoming a friend of Belinda Crossley (later Lady Montagu of Beaulieu).

After three years she “blagged my way” into the Slade School of Fine Art, earning a first class diploma in fine art, drawing, painting and etching. This was the golden era of the Slade, which was undergoing a renaissance under the inspirational direction of Professor William Coldstream, the art critic David Sylvester and the gallerist Helen Lessore.

A mere five years after the war, Blitz damage was still evident in London and the art school operated from the north wing of the quad of University College. Susan lodged in a house of Slade students, her bedroom containing the coke stove that heated the building – her was mother horrified to see her open sugar bowl covered with dust and ashes and her landlord sleeping in a cupboard under the stairs.

She began by drawing from plaster replicas of statues, but enlivened this with judiciously placed pot plants. She soon graduated to painting nude male models, who wore “modesty slips” for the girls.

Rafts of distinguished artists such as Lucian Freud, Graham Sutherland and Stanley Spencer came to talk to the students, who included Euan Uglow (of whom she published a memoir in 2003), Craigie Aitchison (“I thought I’d ended up in paradise”) and Michael Andrews (“Nothing could ever be so good again”).

In their free time they ate as best they could at Bianchi’s in Soho, Jimmy’s or Bertorelli’s. They danced to New Orleans jazz, and Sylvester and Freud guided Susan and others to the Colony Room in Dean Street.

The writer John Moynihan was soon describing Susan Benson as a “girl in stark flesh-clinging ballet-style-black” being twirled around at a party “with super-animated ferocity by her ecstatic partner” – Mike Andrews, who, between 1958 and 1960, produced an unfinished portrait of her at her home in Noel Road, Islington.

In 1953, after three years at the Slade, she gained a travelling scholarship and the Daily Sketch commissioned her to draw towns and social events such as the Fourth of June at Eton and the Royal Academy Private View. She won two prizes, one of £250 for a drawing of Stamford Bridge stadium and another £50 for etching. This enabled her to live in Sicily for a year, drawing and painting peasant life.

On her return to England in 1954, she concentrated on illustration and drawing, with commissions from The Sunday Times, The Observer, Shell Oil and various magazines. In 1963 she drew sketches for her friend Nell Dunn’s Up the Junction which Randolph Churchill judged in The Birmingham Daily Post to “most faithfully reflect” the book’s depiction of Battersea life.

In 1958 Lady Mary Campbell (daughter of the 5th Earl of Rosslyn) sued her husband, Robin Campbell, CBE, DSO, son of Sir Ronald Hugh Campbell (Ambassador to France and Portugal), for adultery (“Girl artist cited”) and was granted an uncontested divorce.

The following year, Susan married him. He had been wounded in the ill-fated raid on Rommel’s headquarters in Libya in 1941, taken prisoner, and had a leg amputated. As Director of Art at the Arts Council during some of its most productive days, he arranged many international exhibitions.

This marriage brought her into the world of people such as Cyril Connolly, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Robert Kee and the ever-tricky author, Julia Strachey. Robin died in 1985.

While bringing up a young family, Susan Campbell turned her attention to cookery books. She collaborated with Caroline Conran, cookery editor of The Sunday Times, on her book, Poor Cook in 1971, which Cyril Connolly described as “a must for families who are beginning to despair of the rising cost of living… Mrs Campbell sweetens our adversity.”

They collaborated further on Family Cook in 1974, which Lucia van der Post preferred as the dishes were lighter and fresher and could be consumed without guilt.

Cheap Eats in London (1975) retailed at 50p and was the result of a never-to-be-repeated experience of eating meals for £1, though by the time she had finished this had inflated to £2. By the end of each week she felt “distinctly queasy”. Her best find was the Globe Dining Rooms in the Balls Pond Road, where an edible meal could be had for 30p.

Other cook books followed, and in 1980 she interviewed the buyers for Harrods marble food halls, judging apple juices, pork pies and food processors.

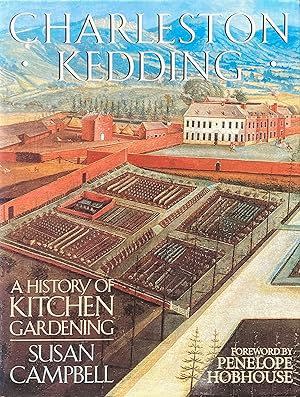

In 1981 she turned her attention to the history of walled kitchen gardens. This was inspired by a visit to Thomas Pakenham’s Tullynally Castle in Ireland, where she found the walled garden intact and operational at a time when many had become derelict.

In 1984 Susan Campbell found a rare, fully functioning kitchen garden at Cottesbrooke Hall for the BBC. In 1987 she published Cottesbrooke, an English Kitchen Garden, which reignited interest in walled kitchen gardens.

For the next 40 years she visited more than 700 such gardens. She published Charleston Kedding (an anagram for kitchen gardens), based on Pylewell Park in 1996, and her most comprehensive book was A History of Kitchen Gardens (2015), with her own illustrations and drawings.

She established the Walled Kitchen Garden Network with the late garden historian, Fiona Grant, in 2001, and advised on the restoration of many famous gardens at houses such as Tatton Park, Hampton Court, Fulham Palace and, most recently, Althorp.

Living on the sea shore in the New Forest, she founded the Beaulieu and District Film Club, greatly enjoyed by nautical figures and retired doctors with yachts, which meets regularly at Buckler’s Hard.

In 1986 she purchased the previously unknown diary of Dr Robert Darwin, father of Charles Darwin. She spent 35 years researching its background, discovering that his garden at the Mount on the banks of the Severn in Shrewsbury, was the site of many of Charles’s early horticultural ventures, and it listed the many plants, both ornamental and exotic, that could be found there. She published this as Dr Darwin’s Garden Diary: 1838-1865 in 2021.

Later in life she studied garden and landscape history at the Architectural Association in London, was vice-president of the Garden History Society and in 2023 was awarded the Veitch Memorial Medal of the Royal Horticultural Society for her outstanding contribution to advancing the science and practice of horticulture.

Susan Campbell had been recommended for a well-earned OBE, but sadly this was not approved in time.

In 2012 she married Mike Kleyn, who survives her with her two sons from her marriage to Robin Campbell.

Susan Campbell, born September 14 1931, died January 2 2024