Suspensions in schools are on the rise. But is that the best solution for misbehaving kids?

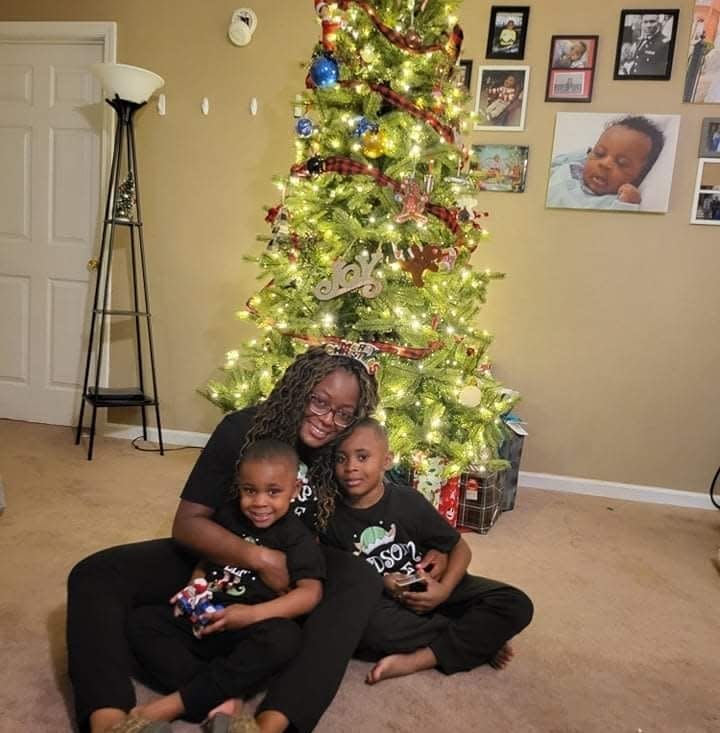

Hearing the phone ring during school hours used to send Destiny Huff into panic mode.

She worried it would be her son’s school calling to say he was suspended again – a constant reality for Huff and her husband when her son began kindergarten at a Louisiana school in 2021.

Huff said her 5-year-old son “would come back from suspension – the school day started at 7:45 – and by 9 o’clock, they'd already called me and he’d been suspended again.”

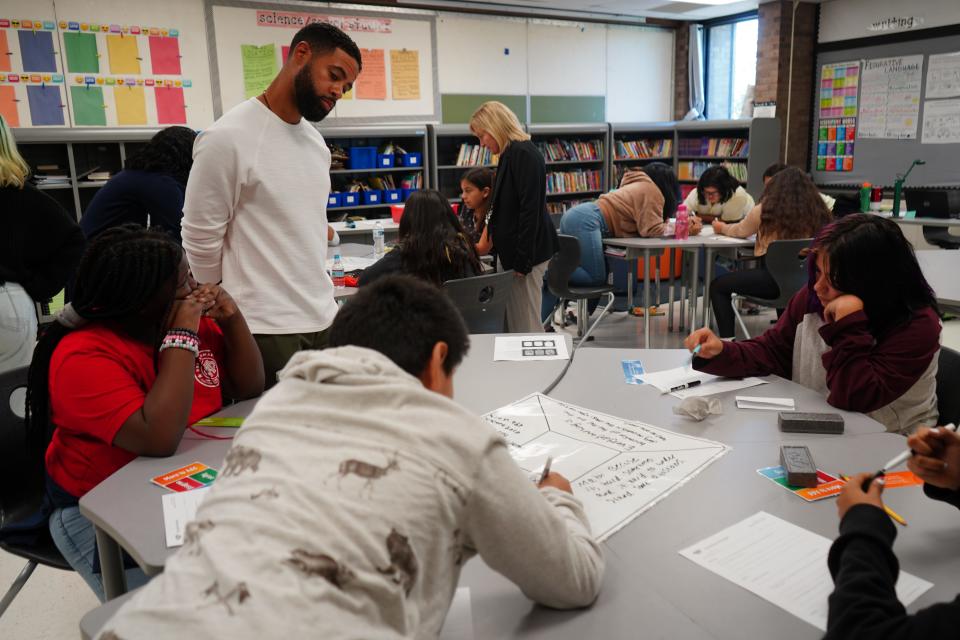

As schools struggle with behavioral issues and teacher shortages in the wake of COVID-19, pre-pandemic efforts to curb zero-tolerance school discipline measures that remove students from their classrooms have largely stalled, with more students being sent home for yelling in class, fighting on campus or talking back to the teacher. But many experts said time in the classroom is vital for students still reeling from the impacts of remote learning and such measures could make it even harder for families, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds, to help their child learn.

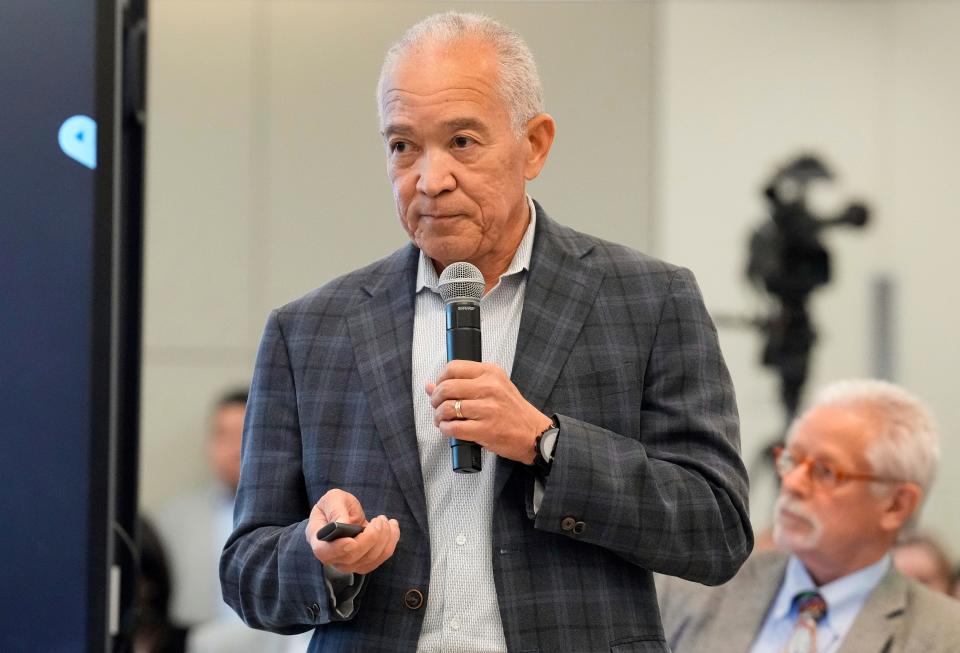

“Discipline is becoming a real issue again and some things that we were hoping were getting better are starting to look like they might be getting worse,” said Jason Okonofua, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, who has studied discipline in K-12 schools.

Experts have also expressed concern over what they call “soft suspensions,” which can include practices such as forcing children to spend time in seclusion rooms, constantly sending a child home from school early and requiring students to do virtual learning as a disciplinary measure.

These practices are generally not recorded as suspensions, but are all detrimental to a child's learning, said Cheryl Poe, founder of Advocating 4 Kids, a nonprofit that advocates for neurodiverse students in public schools.

“The child is still removed out of the educational setting,” she said. “Those should count as missing seat instruction hours.”

Suspensions are growing in some states

Although the U.S. suspension rate has lowered from its peak of 7% in 2010, it plateaued at around 5% for the years leading up to 2018 – the most recent national data available from the Civil Rights Data Collection, a required survey by the U.S. Department of Education administered to public schools nationwide every other school year.

The COVID-19 pandemic shut down schools nationwide in March 2020 and largely closed schools the following academic year, making more recent data collection difficult. Since then, agencies, school districts and states have been trying to catch up.

More: Distracted students and stressed teachers: What an American school day looks like post-COVID

More recent analysis of state-level data does show some troubling trends.

The Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the University of California, Los Angeles, which researches social science issues relating to equity, analyzed California data from the 2019-20 school year. It projected what suspension rates would have been if the school year wasn’t cut short by COVID-19 and found that rates continued to stagnate.

In many school districts – including Elk Grove Unified in Sacramento County and Oakland Unified School District in the Bay Area – there seemed to be an uptick in suspensions prior to the school closures, leading researchers to determine that if the school year had continued, suspension rates might have gone up in the state.

“Despite the strides that California has made in this area, there are many districts where there is no progress – that things have gotten worse,” said Dan Losen, a former director of the center who co-wrote the analysis.

In New York City Public Schools, more suspensions were issued during the first half of the 2022 to 2023 school year, a 27% increase from the same period in 2021. An analysis of data from schools in Washington, D.C., also found that in-school suspensions increased by 16% during the 2021 to 2022 school year.

Three years after schools shut down because of COVID-19, educators have been under pressure to get kids up to speed on the academic and social skills lost during the pandemic. Many students are still struggling with the mental and physical trauma that COVID-19 took on them, a time when they lost family members, witnessed or experienced abuse and spent countless hours on their screens in isolation.

Many educators have leaned on school discipline to handle student misbehavior by suspending or expelling kids and sending them out of the classroom. In late May, the Biden administration issued a letter urging public schools to follow civil rights guidance and avoid discriminatory school discipline measures.

More: American classrooms need more educators. Can virtual teachers step in to bridge the gap?

Why are children suspended from schools?

Huff’s son, who was suspended three times within two weeks, had never had drastic behavioral issues, she said. However, that changed in August 2021, when he began attending an elementary school in the Vernon Parish School District in Louisiana.

“He started to really have some behaviors that we had never seen before,” Huff said, including throwing things and yelling when he would get upset, but not hurting others.

Ellen Reddy, an advocate who fights against suspensions in Mississippi, said children are often suspended for subjective reasons that haven’t changed since she first got involved in this advocacy over two decades ago. Reddy said the children she works with get suspended for various reasons that can range from fights at school to getting on the wrong school bus home.

“They’re still suspending kids for the very same thing – disobedience, talking back, getting out of their seat, going to the bathroom without permission,” Reddy said. “We should be asking more questions versus just right away suspending kids.”

States consider harsher discipline policies

Several states, including Arizona and Nevada, have attempted to bring back harsher disciplinary policies, while others are utilizing practices like seclusion rooms and forcing misbehaving students into remote learning.

Houston Independent School District, the largest district in Texas, drew criticism in late July when it announced they would be eliminating 28 school libraries and repurposing them into “team centers” where educators can host kids for discipline.

In a statement to USA TODAY, the district said these centers are a vital “hub of differentiated or personalized instruction.” Officials stressed a one-size-fits-all approach is not enough to “eliminate the persistent achievement gaps that have adversely impacted" disadvantaged students.

“When necessary, the Team Center will provide students who are struggling or disrupting the traditional classroom environment ... the opportunity to get necessary care and engagement while they access their classroom instruction remotely to ensure they do not lose even a few minutes of learning time,” the school district wrote.

Katherine Wiley, an assistant professor of education at Howard University in Washington, D.C., said removing a student from their classroom in any way is still harmful because “we take them away from their peers, from instruction and we essentially stigmatize them by putting them into a different part of the school building.”

A recent police and Department of Education investigation into McAuliffe International School, a middle school in Denver, found the school placed multiple students of color into seclusion rooms – reportedly referred to by the staff as “incarceration rooms” – without proper supervision last school year. An administrator would either lock the door or hold the door closed while the student was inside.

The room at McAuliffe has “a bolt on the outside of the door and padlocks on the window,” said Pamela Bisceglia, executive director of AdvocacyDenver, an advocacy organization for people with disabilities.

Who gets removed from school the most?

Students with disabilities received nearly a quarter out-of-school suspensions during the 2017-18 school year, almost double the demographic’s overall share of student enrollment of 13%, according to the Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection.

Black students were also disproportionately suspended, only making up 15% of student enrollment, but receiving 38% of out-of-school suspensions that same school year.

These disparities are worse for Black students with disabilities, who only account for 2% of the total student population but make up nearly 9% of out-of-school suspensions.

Okonofua, the UC Berkeley professor, co-wrote a study in April and found that school discipline rates fluctuate greatly throughout the school year and spike during the beginning of the year and after major school breaks. The data analysis also found Black students experience the steepest escalation of discipline compared to any other demographic.

Keith Howard, a civil rights and education law attorney based in Washington, D.C., said race is often intersected with poverty and disability status, making Black children with disabilities from low-income families the most susceptible to school discipline.

“I've been doing this for a long time and so I've seen a lot of good kids getting pushed out of schools for really small reasons and they don't really have any recourse,” Howard said.

Research shows that children’s behavior does not vary based on their race or ethnicity. Rather, “adults' responses to their behaviors are different and they are discriminatory,” which causes disproportionate discipline rates, said Paige Joki, a staff attorney at the Education Law Center in Pennsylvania.

Normal adolescent behavior, like their tendency to take risks and experiment, is often criminalized for students of color, said Kristin Henning, law professor and director of the Juvenile Justice Clinic and Initiative at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

“Everything you know – all the stereotypes tell you that Black children are angry and violent and threatening. So you're looking at these behaviors through that racially biased lens,” Henning said.

‘Not a safe space for him’

Huff and her family still carry the trauma from their experience, even after moving to a new school in Georgia last academic year, where Huff said her son “is doing great and is comfortable.”

“The school psychologist said something really important for us to hear – that he doesn’t understand that school can be a safe space,” Huff said.

Negative encounters with school authority at a young age can cause detrimental impacts to a child’s perception of law enforcement – views that are largely shaped for people during their adolescent years, Henning said.

After her son’s third suspension, Huff, a licensed mental health specialist, and her husband – fearing their son could be permanently removed from the school- contacted the district’s superintendent.

“It was a trickle effect from there. They basically went into hyperdrive of saying ‘we’re sorry you experienced this,’” Huff said. Her son was eventually evaluated and diagnosed with autism and she said their “whole perspective, our whole world, shifted.”

Suspensions largely impact a student’s academic achievement and increase the likelihood they’ll interact with the justice system, said Abigail Novak, an assistant professor in the Department of Criminal Justice and Legal Studies at the University of Mississippi.

Novak’s 2019 study found that children who are suspended by age 12 are more likely to report justice system involvement at age 18.

“I don't see the utility or the effectiveness of pushing a child out of education that is already at risk. It doesn't make sense,” Howard said. “You're just getting rid of the problem and that problem becomes a community problem.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: School suspensions on the rise: Why experts say it’s not a good thing