Is the swastika a symbol of hate or peaceful icon? Faith groups try to save reviled emblem

For many, the cross with bent arms is a painful symbol of evil, hate and genocide.

For others, it's an ancient sign of peace and prosperity.

For all involved, it's an issue fraught with history, ingrained experience and high emotion.

As hate crimes – including those against Jews – proliferate across the country, and lawmakers mull legislation defining symbols of hate, some are struggling to ensure that the swastika – which Dharmic cultures hold dear – doesn’t get caught up in the fray.

The California Senate has passed AB 2822, which equalizes the penalties and enforceable locations for what the bill calls “three pervasive and extremely harmful symbols of hate – burning crosses, swastikas and nooses.” The bill is supported by the Anti-Defamation League, interfaith groups and associations representing California’s sheriffs and school boards.

Others support the bill in spirit, but say using the word “swastika” to describe the Nazi emblem is not only incorrect, but potentially dangerous. They note that the symbol held sacred by an estimated 2 billion Hindus, Buddhists and Jains worldwide existed for at least 5,000 years before being misappropriated by Hitler’s Germany and, more recently, white supremacists.

“Hitler never used the word,” said T.K. Nakagaki, a Buddhist priest and author of “The Buddhist Swastika and Hitler’s Cross: Rescuing a Symbol of Peace from the Forces of Hate.” “He only used the word ‘Hakenkreuz.’” A word meaning “hooked cross.”

“For a lot of Asian people, this is the most important symbol,” Nakagaki said. “It’s a representation of noble truth, or even Buddha himself. It’s a major symbol around the world, one of the most interfaith symbols that has ever existed.”

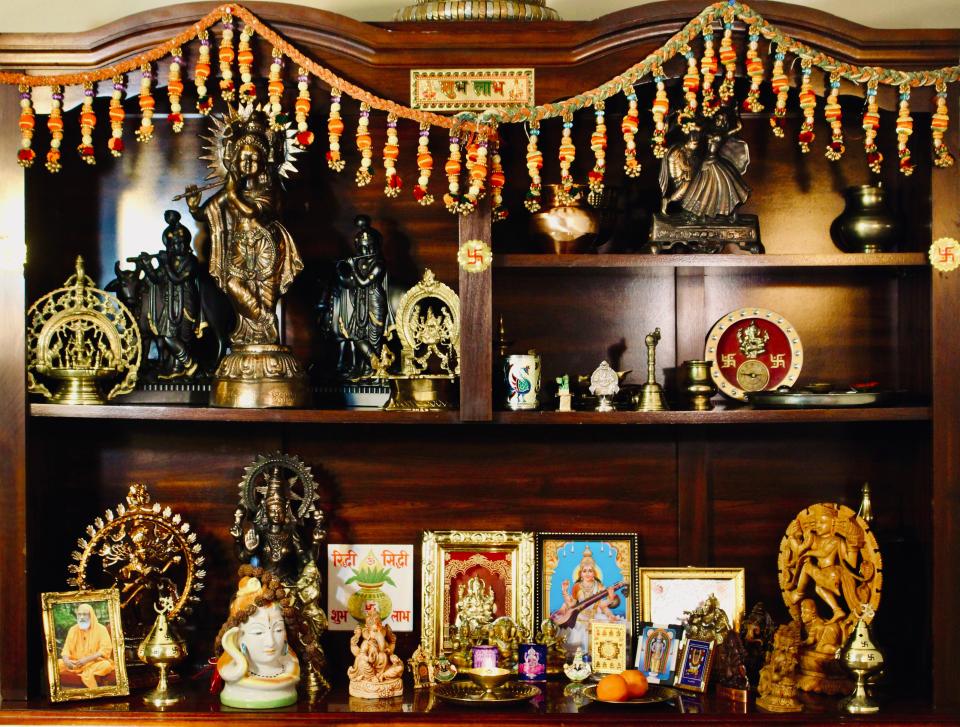

Not making that distinction, some say, subjects their communities in the U.S. to misunderstanding, harassment, scorn and danger. Nearly 8 million Hindus, Buddhists and Jains call the U.S. home, with the symbol found on Buddhist temples, in household shrines and displayed during the Hindu festival of Diwali.

“Words really matter and have a lot of power,” said Pushpita Prasad, a board member for the Coalition of Hindus in North America, known as CoHNA. “When you use the word ‘swastika’ in the context of hate symbols, that’s really impacting our religious freedom.”

Confusion over the word and the symbol itself has led to misunderstandings. Earlier this year in Los Altos, California, a youth summer camp shut down after its staff quit en masse upon discovering Buddhist swastika tiles from the early 1900s on a building on the camp’s grounds.

“There was no Nazi connection,” Prasad said. “But for generations, people have been trained to have such a visceral reaction that they cannot stop to think about the proper context.”

In 2020, Simran Tatuskar, then-student body president of Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, faced backlash after suggesting that the swastika’s peaceful origins be taught in the school’s curriculum, a suggestion she made in response to proposed New York legislation that, like California’s bill, included the swastika among symbols of hate.

Tatuskar, who is Hindu, eventually issued an apology and clarification.

“For us, this whole idea of conflating the swastika with the Hakenkreuz is horrible,” said Gokul Kunnath, president of the United States Hindu Alliance. “It’s like, Peter kills Paul and a Hindu is blamed. We had nothing to do with this.”

While those embracing the cause say they don’t mean to diminish the symbol’s deeply painful associations for Jews worldwide, they also don't want to lose a spiritual and cultural mainstay.

“We definitely empathize with the Jewish community,” said Nikunj Trivedi, president of CoHNA. “They’ve suffered through genocide and the Holocaust, and hate crimes have increased in recent years, so there’s actually a pent-up demand to create legislation around hate. But we’re not going about doing it the right way.”

A matter of 'three little words'

California Assemblywoman Rebecca Bauer-Kahan, AB 2822’s sponsor, said she drew up the bill in response to a November 2020 incident in Fairfax, California, in which a man placed stickers bearing images of the “Nazi emblem” on telephone poles.

“Even though the individual was identified, district attorneys could not charge as the law was silent on this type of terror,” Bauer-Kahan told USA TODAY in a statement. “AB 2282 will equalize the penalties and locations for which hate crimes can be charged” for the specified symbols.

FBI statistics indicate that hate crimes reached a 12-year-high in 2020, with more than 11,000 reported incidents, compared with the previous year’s total of 8,500. The true number is likely higher, as many such crimes go unreported.

Bauer-Kahan’s bill initially made no distinction between the symbol and the Dharmic swastika when it was introduced in February, but she amended it to include a reference to the “Nazi Hakenkreuz” after meeting with CoHNA and dozens of other Dharmic groups.

However, the bill still says the Hakenkreuz was also known as the "Nazi swastika" – with the latter term used multiple times throughout the bill. CoHNA leaders said they had asked that the words “incorrectly known as” be added before such references, but got no response.

As such, they support the bill’s intent, but not in its current wording.

“If you can insert new language, you can certainly insert those three words,” Trivedi said. “They’re creating the idea that there’s a bad swastika and a good swastika, and that’s just not the case.”

As the bill heads to the governor’s desk, Trivedi said the outcome is important because California's legislative measures often act as a template for similar legislation around the country.

“If you don’t fix the issue at that core level, you’re going to have a spillover effect,” he said. “Then it’s a game of whack-a-mole."

Bauer-Kahan, who according to her biography is the granddaughter of refugees who came to the U.S. to escape the Holocaust, did not respond directly to a question about the wording but in her statement expressed gratitude to the Hindu community for sharing its concerns.

“This is the first step in supporting our Hindu, Buddhist and Jain communities, and showing their sacred and peaceful swastika should not be confused with the hateful Nazi emblem,” she said.

A ubiquitous symbol that 'permeates our lives'

It's not the first time CoHNA has fought this battle, with similar legislation having been introduced in New York, New Jersey and Maryland.

“We understand the intent of the bills,” Prasad said. “People want to do the right thing and we support that, but there is a lot of ignorance and misunderstanding around the word ‘swastika’ as it is used in the West.”

CoHNA leaders said New Jersey’s bill is progressing with amended language suggested by the group, referencing a “Nazi emblem” rather than a swastika. Bills in New York and Maryland, meanwhile, have been withdrawn for further discussion, Trivedi said.

“I think they realized there are better ways to do it,” he said. “By trying to create legislation around hate, you’re actually triggering hate against other communities that hold the swastika as sacred.”

The symbol is revered by Hindus, Buddhists and Jains around the world. Prevalent in East and South Asia, it’s also embraced by Sikhs and some Native American cultures, including the Navajo.

In its original form, the Sanskrit word translates to "well-being," and for many, the symbol is part of popular religious or cultural customs. During Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights held during October and November, swastikas are depicted as part of a rangoli, a patterned design created from rice or flour to connote prosperity and good luck.

“It’s prominently displayed in the temple, in marriage rituals or in the traditional head-shaving ceremony for boys as a symbol for prosperity,” Trivedi said. “It’s ubiquitous. It permeates our life throughout the entire year.”

Prasad, like many Hindus, featured the symbol on her wedding invitation.

“I was not wishing death to myself or my guests,” she said. “If people get the context, it becomes easy to understand.”

Still, problems arise. Prasad has heard of deliverymen defacing rangolis displayed outside doorways, or home altars suspiciously eyed by neighboring kids invited over to play.

“When we buy a new car, we might take it to get it blessed, and the priest will do a ceremony that involves drawing a swastika, usually in turmeric powder,” she said. “But people here often don’t do it because it will draw vandals. They don’t want to get keyed. People self-censor.”

When Nakagaki, the Buddhist priest and author, first came to the U.S. in 1986, he formed a ceremonial swastika from chrysanthemums at his temple as he had learned to do in his native Japan but was quickly admonished by a colleague not to do so because of the reactions it might elicit.

And during the pandemic, Trivedi said, he received a call from a CoHNA member who’d participated in a Zoom meeting and was reported to his company’s human resources department by a colleague who noticed swastikas displayed in the background as part of a family shrine.

“These are the things you see when people are not educated,” Trivedi said. “And sometimes, people just don’t want to change, don’t want to understand – because no matter how you slice and dice it, for them this is a symbol of hate.”

Bridging differences through dialogue

The visceral reaction among many to the symbol is unsurprising given its nefarious use by the Nazis and the brutal murder of 6 million Jews during their conquest of Europe.

Jeff Kelman, a Holocaust historian based in New Hampshire, began studying the symbol as he mulled possible topics for his master’s thesis in Holocaust studies at Gratz College in Melrose Park, Pennsylvania.

As a Jew growing up in Boston, he vaguely knew that the symbol had roots in Hinduism, but as he dug deeper, “I saw that Hitler himself only ever referred to the Hakenkreuz – and given how many classes I’d had about anti-Semitism, it baffled me that we didn’t have more literature on that.”

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's Holocaust Encyclopedia, interest in the symbol was revived by the 19th-century excavations of German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, who discovered hundreds of such symbols at the ancient city of Troy.

Having seen similar symbols on German pottery, the site said, Schliemann took the shape to be linked to "our remote ancestors," and other scholars more broadly posited that it reflected a shared Aryan culture across Europe and Asia. The latter notion is likely what prompted its appeal among racist and nationalist groups in Germany – including the Nazis, who adopted it in 1920.

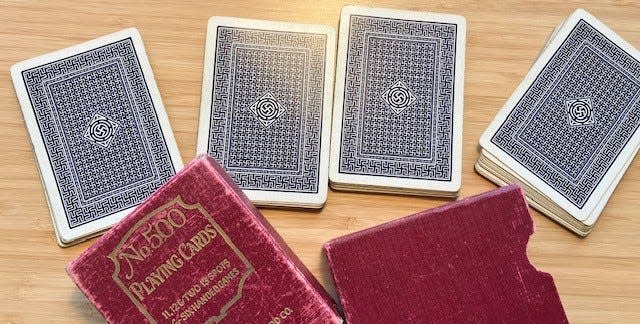

Kelman's mission now is to help educate others about that distinction and to let people know that prior to its Nazi appropriation the symbol's resurgence had resulted in its popularity as a token of good fortune. It was widely used secularly in the U.S. – on playing cards and poker chips, in Coca-Cola ads or on newspaper coupons, “like for a dollar off your next tailoring or whatever.”

A town called Swastika even exists in New York state, where municipal leaders in 2020 voted to keep the name, based on the word’s Sanskrit origins, after complaints surfaced from individuals visiting the area. The vote spurred state Sen. James Skoufis to propose legislation that would force the town to change its name; that bill is still in committee.

Throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, Kelman said, The New York Times in its international coverage referred to the Hakenkreuz, but around 1934 began using the word “swastika” in its place with no explanation that he could find. The new wording became standard, he said.

Now, “it’s Jewish communities we need to reach out to, first and foremost,” Kelman said, adding that he’s addressed many such groups himself and found them largely receptive. “I say, the last thing we want is for Hitler’s symbol to continue to do harm.”

Kendall Kosai, director of the Anti-Defamation League’s Western Division, said that while the ADL recognizes the symbol as a positive symbol throughout East Asia, “it’s also important to show that the symbol is a particular pain point within the Jewish community. For many it remains hurtful and intimidating. It’s a tricky balance – but overall, context matters. We have to take time to educate through dialogue.”

Kosai himself took part in an online webinar held this month to discuss the California bill with the leader of a national Hindu group. He cautioned that despite such dialogue, for many, the evil associated with the Nazi symbol is so deeply embedded that its redemption is unlikely.

“It’s not an on/off switch,” Kosai said. “We’re not going to resolve it overnight.”

Greta Elbogen, a Holocaust survivor whose grandmother and cousins perished in Auschwitz, believes the answer lies with the young.

Elbogen was born in 1938 as the Nazis forcibly annexed Austria. She went into hiding with relatives in Hungary, immigrated to the U.S. in 1956 and became a social worker. She’s now a poet and educator in New York.

For a long time, the swastika held nothing but terror for her – until Nakagaki, the Buddhist priest and author, taught her otherwise. The two connected a decade ago and he invited Elbogen to speak at a panel featuring survivors of both the Holocaust and Hiroshima.

At the event, Elbogen said, the survivors were neither Japanese nor Jewish.

“We were just human beings who were victimized,” she said. “We have to come together and step out of it and see how we can make a difference. We have to break these old ways of looking at the world.”

Now, she also works to educate, though the lingering vitriol felt by some in her community toward the symbol was so strong that she eventually felt she had to walk away.

“I could feel the fear, the history not allowing them to step out,” she said. “I know what other people feel, and I feel bad that they feel that way. But I refuse to.”

She considers herself a humanist now, working with students to express themselves through art.

“The Jewish community will figure itself out,” Elbogen said.

For many elders, she knows it’s too late: “The young people are ready. And if you don’t stand up for truth, lies can win.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Faith groups fight to distance swastika practices from others' pain